All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

CanMEDS Roles addressed: Expert, health advocate, communicator

Case Description

A 52 year old lady attends the emergency department with a several week history of palpitations. She is found to have atrial fibrillation. You have started a beta blocker and she is in a stable condition for discharge. You evaluate the need for stroke prevention and discuss the options with her.

Main Text

A 52 year old lady attends the emergency department with previously unrecognized atrial fibrillation. She has had intermittent palpitations for a month or so and her first ECG showed atrial fibrillation at a rate of 110 beats per minute. Now, four hours later, her heart rate is 80-90 and she is keen to go home.

You are wondering if this new diagnosis will mean she is at risk of stroke. How do you assess this?

There are several scores which estimate the stroke risk, including CHADS2, CHADSVASC and in Canada, we have the CHADS65.

| CHADS2 score | Points |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Age ≥ 75 | 1 |

| Diabetes | 1 |

| Prior stroke / TIA / systemic embolism (limb / gut / spleen etc) | 2 |

| CHADSVASC score | Points |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Age 65-75 Age >75 | 1 2 |

| Diabetes | 1 |

| Prior stroke / TIA / systemic embolism (limb / gut / spleen etc) | 2 |

| Female sex | 1 |

| Vascular disease | 1 |

The CHADSVASC has additional points for age >65, female sex and a history of vascular disease (such as aortic aneurysm or lower limb arterial disease). The Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians 1 and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2 recommend using yet another rule version, the CHADS65. The CHADS65 is a hybrid rule which includes the same variables as the CHADS score with a lower age cut-off of 65 (also used in CHADSVASC).

There are two ways you can use these sores in the emergency setting.

1. You can use the estimated yearly risk of stroke to inform your patient about the risks and benefits of starting on anticoagulation.

Clinical pearl: The simplest way to convert the CHADS2 score into a clinically meaningful concept is (CHADS2 score x 2) = yearly risk of patient having a stroke. For example, this patient has a CHADS2 score of 2 (for diabetes and hypertension), so her risk of having a stroke is 4% within one year. The CHADS2 score has been validated in multiple settings and populations. This rule of thumb is a rough estimate of the stroke risk which approximates well. It is not a published rule but one I use in my clinical practice every day.

2. You can use a score to decide whether or not to recommend anticoagulation for your patient (to establish a binary result; anticoagulation recommended / anticoagulation not recommended) 3. The Canadian guidelines developed the CHADS65 rule in order to make this decision simple. The Canadian Cardiovascular Society recommends that people over the age of 65 with atrial fibrillation should be started on anticoagulation. The Canadian guidelines recommend that patients under the age of 65 with a history of: hypertension, heart failure, diabetes or prior stroke/TIA/peripheral embolism are also offered anticoagulation.

The yearly stroke risk can be reduced by prescription of either aspirin or an anticoagulant. Aspirin will reduce the stroke risk by around 20%. Anticoagulation will reduce the stroke risk by 60-80% 45. This patient should be offered anticoagulation.

[bg_faq_start]Step 1: Review blood results

Before offering an anticoagulant, always review the patient’s blood count and creatinine.

- Use an app such as MDcalc to calculate the creatinine clearance using the patient’s weight, age, sex and creatinine. Record the creatinine clearance in your notes.

- Check for anemia which might suggest occult bleeding. If you are concerned about bleeding, don’t start anticoagulation.

- Check that the platelet count is normal. Never start anticoagulation in patients with a platelet count of <50. You are strongly advised not to start anticoagulation in patients with a platelet count of 50-75.

Step 2: Review medications

- DOACs are contraindicated with certain other medications. The important ones to remember are PHENYTOIN, PHENOBARBITAL, CARBAMAZEPINE, RIFAMPIN, ANTI-HIV DRUGS, CYCLOSPORINE. Some antibiotics (clarithromycin, erythromycin) will also interact, but unlike the others, patients take antibiotics for a just a few days.

- Take note if the patient is already prescribed aspirin. Consider referral to a specialist (for example a cardiologist appointment) to review need for continued antiplatelet therapy.

Step 3: Has the patient had valvular heart surgery?

The DOACs are contraindicated for stroke prevention in patients who have undergone heart valve surgery.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Step 4: Has the patient had major bleeding in the past year?

Ask the patient whether they were treated for bleeding in the gut, head, urine or elsewhere. A recent major bleeding episode increases the chances of recurrent bleeding after anticoagulation is started. Do not start anticoagulation today and request a specialist opinion.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Step 5: Does the patient have liver cirrhosis?

Severe liver disease is associated with an increased risk of bleeding, which will be amplified when anticoagulation is started. Be cognizant of esophageal varices. Do not start anticoagulation today and request a specialist opinion.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Step 6: Is the patient pregnant or breastfeeding?

DOACs are contraindicated in this case.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Step 7: If the patient has no contraindication to a DOAC

Check that the costs of DOAC medication will be covered. In Canada, DOACs are often covered for stroke prevention by provincial health plans, when the person is ≥ 65 years old. Otherwise, they require a private drug plan. DOACs cost around $4 per day in Canada. This may not be affordable for some people. Warfarin is much less expensive (around $10 per month).

[bg_faq_end]The DOAC dosing depends on creatinine clearance. A simple approach to to learn the doses of one DOAC and, at least initially, prescribe only that DOAC.

| Anticoagulant | Creatinine clearance | Dosing |

| Apixaban | > 25 ml/min | 5mg twice daily 2.5mg twice daily if 2 out of the following 3: age ≥ 80, weight ≤ 60 kg, creatinine ≥ 133 mmol/L |

| Rivaroxaban | ≥ 50 ml/min 30-49 ml/min | 20 mg daily 15 mg daily |

| Dabigatran | ≥ 50 ml/min 30-49 ml/min | 150 mg twice daily (consider 110 mg twice daily in elderly or increased risk of bleeding) 110 mg twice daily |

| Edoxaban | ≥ 50 ml/min 30-49 ml/min | 60 mg daily (reduce to 30mg daily if weight < 60 kg or on P-gp inhibitor medication) 30 mg daily |

| Warfarin | any | Tailored dosing to achieve INR 2.0 – 2.5. This usually takes 5-10 days and involves blood testing every 3 or 4 days until INR > 1.9. |

What should you discuss with the patient?

Explain to the patient their yearly risk of having a stroke.

Anticoagulants are different from other medications because they come with a higher risk of serious side effects: bleeding. You should spend time discussing this with your patient. Patients may not recall your entire conversation so you should give them written information about the drug you provide, and arrange for follow up in a clinic or else with their family practitioner.

The patient should understand that all anticoagulants have a small risk of bleeding. It is important to explain how bleeding could present (headache, stroke, melena, hematemesis, hematuria or excessive bruising). In general, the risk of major bleeding is between 2 and 4% per year 6. The risk is higher in people with renal impairment, who have had prior bleeding, or who take antiplatelet medications or NSAIDs.

There are subtle differences between the DOACs and warfarin. DOACs are associated with fewer intracranial bleeding events, but more gastrointestinal bleeds compared to warfarin. However, in general, the amount of bleeding is similar overall 7 8 9.

Although there is no reversal agent for rivaroxaban, apixaban or edoxaban, patients who were randomized to a DOAC rather than warfarin in the phase 3 trials had better outcomes after major bleeding than those who were prescribed warfarin10. The lack of a reversal agent should not prevent prescription of these agents.

Anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation pearls

If you start warfarin you must have a system in place to monitor the INR, at least until it is stable between 2.0 and 2.5. Thereafter, you may refer the patient back to their family practitioner.

Never start anticoagulation in patients already taking dual antiplatelet drugs (such as both aspirin and clopidogrel). The risk of bleeding is too high 11. Consider referring for specialist advice.

Patients who take aspirin for primary prevention should stop their aspirin when they start anticoagulation. This will reduce their bleeding risk 12.

Let the family practitioner know that you have started an anticoagulant (along with the type and dose).

Case Conclusion

You talk to your patient about her risk of stroke. You explain the risk is around 4% chance of a stroke in a year. You say that an anticoagulant would protect her against having a stroke. She takes a prescription for rivaroxaban and an information sheet about the drug and about atrial fibrillation. She will see her family practitioner within two weeks to review how she feels on this medication, and you fax a letter to the family practitioner to inform them of the new diagnosis and medication.

Main Messages

- DOACs are the mainstay for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation.

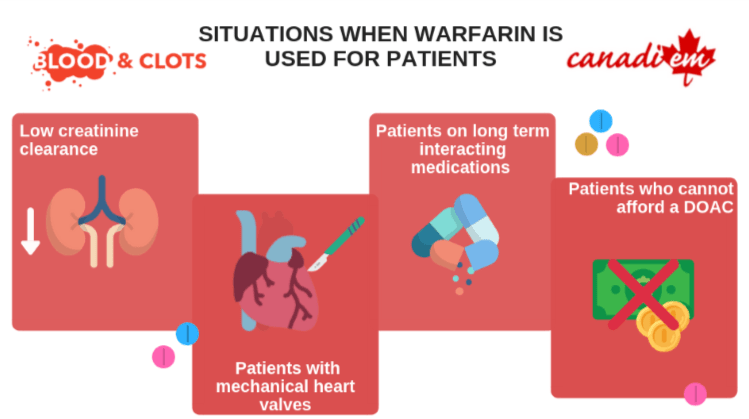

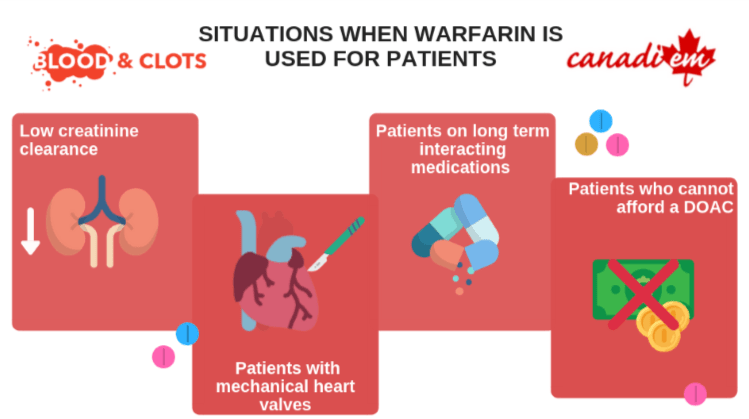

- Warfarin is the anticoagulant of choice for patients with poor renal function, heart valve surgery, prescribed certain other drugs and who do not have drug coverage.

- Ensure the patient understands the drug you are starting is an anticoagulant, as well as the indication, risks and benefits.

All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

This post was reviewed by Mark Woodcroft, Teresa Chan and copyedited by Rebecca Dang.