All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

CanMEDS Roles addressed: Medical Expert, Scholar

Case Description

You are assessing a 76 year old lady who takes warfarin for stroke prevention because she had a mechanical aortic valve replacement 4 years ago. She was at the preoperative clinic this morning because she will have a knee replacement surgery in a weeks time. The anesthesiologist said they would like to perform a spinal block for the surgery, and the surgeon says the patient must come off her warfarin before he can operate. She tells you she is worried about having a stroke if she stops her warfarin.

You are wondering how to advise her. Can you stop the warfarin for a week before her surgery? Do you need to prescribe ‘bridging’ anticoagulation? When should the patient restart her warfarin?

Main Text

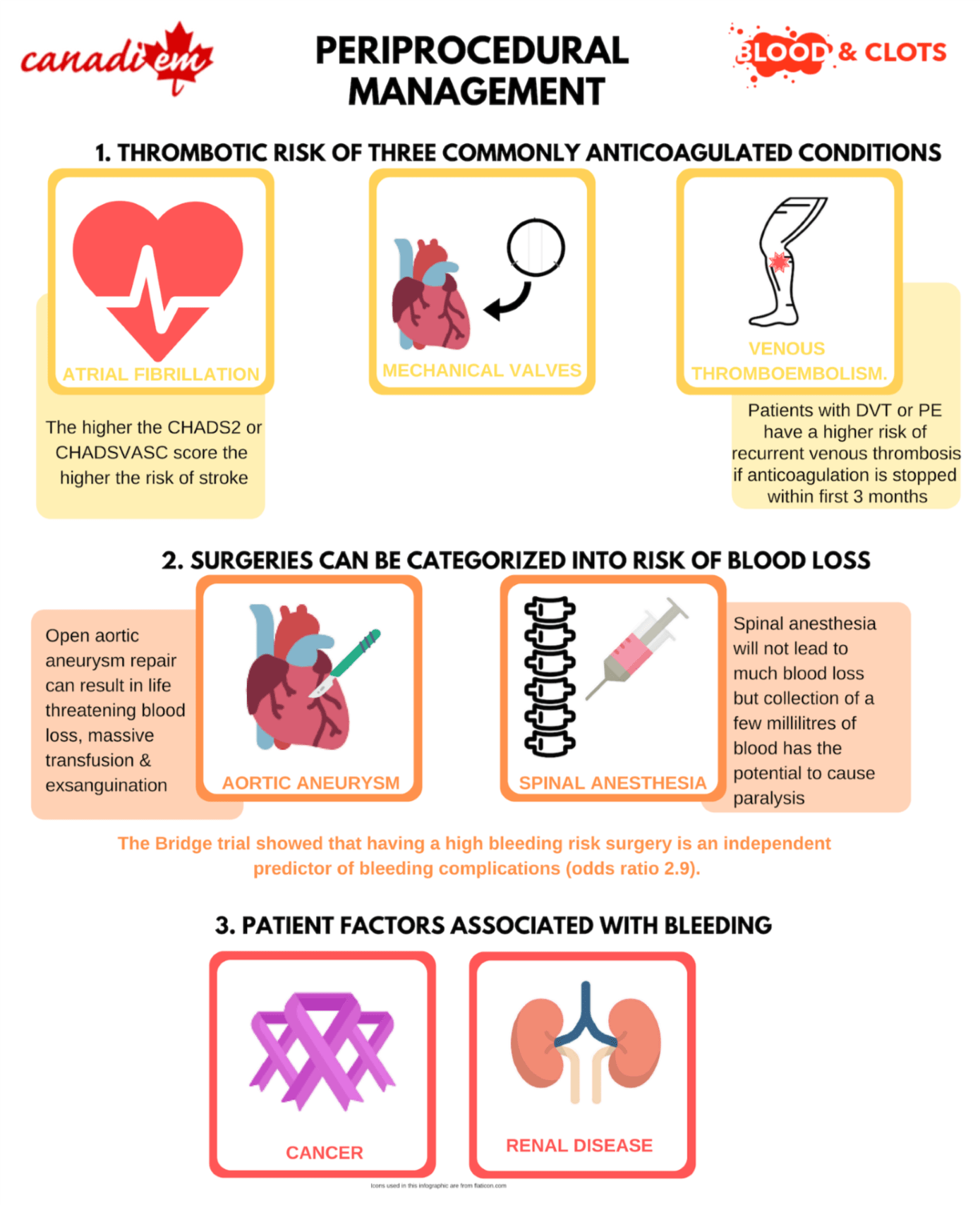

There are three factors which guide periprocedural management of warfarin.

- The thrombotic risk (indication for anticoagulation).

- The bleeding risk for the planned procedure or surgery.

- The patient’s individual bleeding risk.

Assessing the thrombotic risk

In this section we will review the thrombotic risk of three commonly anticoagulated conditions: a) atrial fibrillation; b) mechanical valves; c) venous thromboembolism.

a) Stroke risk in atrial fibrillation

The CHADS2 and CHADSVASC scores are well established risk stratification tools for estimating the risk of stroke in atrial fibrillation. You can use either to calculate the stroke risk. The greater the number of points, the higher the stroke risk. Patients with a CHADS2 score of 5 or 6 (or CHADSVASC 7 to 9) very likely have a higher risk of stroke during the perioperative period than patients with scores of 0-4. As yet, there has been no study that included a sufficient number of high risk atrial fibrillation patients to demonstrate this in the perioperative setting.

The Bridge trial 1 reported an overall embolic rate of 0.39% (7/1913) in patients with atrial fibrillation who had interruption of their warfarin for a procedure.

| CHADS2 score | Points |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Age ≥ 75 | 1 |

| Diabetes | 1 |

| Prior stroke / TIA / systemic embolism (limb / gut / spleen etc) | 2 |

| CHADSVASC score | Points |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Age 65-75 Age >75 | 1 2 |

| Diabetes | 1 |

| Prior stroke / TIA / systemic embolism (limb/ gut/spleen etc.) | 2 |

| Female sex | 1 |

| Vascular disease | 1 |

b) Stroke risk with mechanical heart valves

Mechanical (metallic) heart valves are associated with stroke and peripheral emboli. Patients with mechanical heart valves are anticoagulated with vitamin K antagonists (usually warfarin in Canada and the US), to prevent stroke. Mechanical mitral valves have the highest risk of stroke. A recent Canadian cohort reported a yearly stroke rate of 2.3% among anticoagulated patients with mechanical mitral valves and 1.4% in patients with aortic valves 2. In general, patients with mechanical mitral valves are thought to be at higher risk of stroke than those with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Those with mechanical aortic valves are considered to have a risk of stroke that is equivalent to atrial fibrillation patients with CHADS2 scores or 3 or 4. There has been almost no research on perioperative interruption of warfarin in these patients.

c) Venous thrombosis risk in patients treated for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

One study reported a 1.8% rate of recurrent venous thrombosis among warfarinized patients who underwent surgery 3. Cancer patients were noted to have a higher risk of recurrence. Patients diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism have a higher risk of recurrent venous thrombosis if anticoagulation is stopped within the initial three months of treatment 4. If possible, surgery should be postponed until three months after the diagnosis of a new clot. Those with a recent history of venous thrombosis who require immediate surgery are considered high risk for recurrent venous thrombosis.

Assessing the bleeding risk of the surgery or procedure

In general, surgeries can be categorized into risk of blood loss. The risk may manifest in a variety of ways: for example an open aortic aneurysm repair could result in life threatening blood loss, massive transfusion and exsanguination with poor hemorrhage control. Spinal anesthesia will not lead to much blood loss but collection of a few millilitres of blood has the potential to cause paralysis. In contrast, a facial skin graft is unlikely to cause life threatening bleeding but the skin graft may not heal if there is a wound hematoma

The Bridge trial 5 showed that having a high bleeding risk surgery is an independent predictor of bleeding complications (odds ratio 2.9). High bleeding risk procedures included major intra-abdominal surgery, major orthopedic surgery, peripheral arterial revascularization, urologic procedures, pacemaker/defibrillator insertion, biopsy of a visceral organ, polypectomy, and procedures more than 1 hour.

A comprehensive list of procedures and the risk of bleeding has been catalogued by Thrombosis Canada and can be found here.

The patient’s individual bleeding risk

Cancer is not only a risk factor for recurrent venous thrombosis, but also a risk factor for bleeding during periprocedural interruption of anticoagulation 6. Renal disease 5 and a history of major bleeding 6 have also been identified as risks for bleeding.

In our case, above, this lady takes warfarin to prevent stroke from a mechanical aortic valve, which is an intermediate stroke risk. She is having a high bleeding risk surgery (knee replacement) as well as a high bleeding risk procedure (spinal anesthesia). She is otherwise healthy, so there are no patient factors that increase her bleeding risk.

Her anticoagulation plan should include 1). When she should stop her warfarin, 2). When she can restart her warfarin and 3). A decision of wether she should be prescribed low molecular weight heparin bridging.

How to choose a management strategy

When to stop warfarin

Warfarin takes four or five days for the anticoagulation effect to wear off. On the day of surgery, the International Normalized Ratio (INR) should be <1.4. This might depend on the surgery and the surgeon’s concerns around the risks of beeding. This means that the last warfarin tablet is taken 6 days preoperatively. There should be five full days when the patient takes no warfarin. Always check the INR prior to surgery. In our Thrombosis clinic we check the INR the day prior to surgery . If the INR is >1.4 we give a 2mg dose of vitamin K, so that the surgery does not need to be canceled.

When to start warfarin

Warfarin works by inhibiting the effects of vitamin K on the liver, which in turn, suppresses the hepatic production of clotting factors II, VII, XI and X. The whole process will take several days (between 5 and 10 usually) to reach therapeutic levels.

There are a few golden rules about restarting warfarin after surgery:

- Don’t start warfarin until the patient is eating and drinking. Patients become vitamin K deficient when they have poor dietary intake. Starting warfarin in this scenario will result in unstable and supratherapeutic INR levels. This is never a good situation after surgery. The Bridge trial found that INR levels >3.0 in the postoperative period were associated with bleeding 5.

- Don’t start warfarin while the patient has an epidural catheter in place. Removal of the epidural catheter in an anticoagulated patient is a risk for epidural or spinal hematoma and associated paralysis.

- Don’t start warfarin if there is a concern that the patient has postoperative bleeding, or there is a risk they may go back for emergency surgery.

- If the patient is eating and drinking, there is no epidural catheter and they are not actively bleeding, restart warfarin as soon as possible. It will take many days to reach a therapeutic INR. It may be very reasonable to start on the evening of the procedure. Remember, in an emergency, warfarin can be completely reversed.

When and how to bridge a patient Bridging is the practice of replacing warfarin with low molecular weight heparin injections in the days immediately before or after a procedure. Once common place for every surgery, the Bridge trial 1 has changed practice. This trial randomized patients with atrial fibrillation and at least one point on the CHADS2 score to receive either full dose low molecular weight heparin or else placebo bridging. The low molecular weight heparin was given for three days prior to the procedure and started again postoperatively day 1 or 2, until the INR was therapeutic. Patients who were bridged had more bleeding (3.2%, 21/895 versus 1.3%, 12/918). There was no difference in the rate of stroke (0.4%, 4/895 versus 0.3%, 3/918).

Current guidelines, including the American College of Cardiology 7 , suggest reserving low molecular weight heparin bridging for patients at high risk of stroke, such as patients with CHADS2 of 5-6 or CHADSVASC of 7-9. Bridging therapy is also recommended for patients with mechanical valves and patients with a recent history of stroke. These recommendations are based on expert theory. The Bridge trial had few patients at high risk of stroke and there have been no trials on patients with recent stroke or mechanical heart valves.

What dose of low molecular weight heparin should you use for bridging?

Patients who receive full dose low molecular weight heparin for bridging have a higher risk of bleeding in the perioperative period compared to those who are given intermediate or prophylactic dose low molecular weight heparin 8. A meta-analysis showed no increase in the risk of stroke with intermediate / prophylactic dose low molecular weight heparin 8. There are no head-to-head bridging comparisons for different doses, so it makes sense to choose the dose based on the risk of clotting (high risk being mechanical valves and high risk atrial fibrillation) and the bleeding risk (type of surgery, renal impairment, and history of bleeding).

How can you minimize the risk of bleeding?

There are a number of ways that you can minimize the risk of bleeding. Here are some top tips for safer periprocedural management of patients who would otherwise need anticoagulation:

- Aspirin use in the periprocedural period is associated with bleeding 5, 9. Unless a patient has had a recent stroke or coronary stent, stop aspirin a week before surgery and do not restart until postoperative day 8.

- Calculate the patient’s creatinine clearance before prescribing bridging. Low molecular weight heparin should be avoided in patients with a creatinine clearance <30 ml/min.

- Don’t bridge a patient unless they have atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score of 5 – 6, or else a CHADSVASC score of 7 – 9. Other indications include stroke within 3 months, venous thrombosis diagnosed within 3 months or a mechanical heart valve.

- Consider using prophylactic dose or reduced dose low molecular weight heparin instead of full dose.

- Day 1 postoperatively give prophylactic dose low molecular weight heparin and increase the dose over a period a days if you need to.

- Monitor the INR closely once you restart warfarin and don’t restart warfarin until the patient is eating and drinking.

- Stop bridging the patient as soon as the INR is therapeutic. This may require daily INR tests which can be challenging when the patient has gone home.

Case Conclusion

The patient is to have a knee arthroplasty under spinal anesthesia. Both of these procedures are high risk for bleeding. She has a mechanical mitral valve which is an intermediate risk of thrombotic complications. She has no additional bleeding risks with normal renal function and no prior bleeding in the past.

You decide to bridge her by giving her the prophylactic dose low molecular weight heparin. You give her the following calendar.

| DAY IN RELATION TO SURGERY | WARFARIN | LOW MOLECULAR WEIGHT HEPARIN (LMWH) |

| -6 | Take last dose of warfarin | No LMWH |

| -5 | No warfarin | No LMWH |

| -4 | No warfarin | No LMWH |

| -3 | No warfarin | Prophylactic dose LMWH |

| -2 | No warfarin | Prophylactic dose LMWH |

| -1 | No warfarin | Prophylactic dose LMWH |

| SURGERY DAY | No warfarin | No LMWH |

| +1 | Warfarin at 2 x normal dose | Prophylactic dose LMWH |

| +2 | Warfarin at 2 x normal dose | Prophylactic dose LMWH |

| +3 | Normal warfarin dose and INR | Prophylactic dose LMWH until INR 1.9 or more |

Main Messages

When you plan interruption of warfarin for a procedure or surgery, always assess

- The patient’s thrombotic risk

- The bleeding risk associated with the procedure or surgery

- The patient’s bleeding risk

New evidence suggests that bridging will do more harm than good in patients with a CHADS2 score of 0 – 4 or CHADSVASC score of 0 – 6.

Consider bridging in patients with CHADS2 of 5 – 6 or CHADSVASC of 7 – 9, patients with a mechanical heart valve and patients with either a stroke or venous thromboembolism within the past 3 months.

All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

This post was reviewed by Teresa Chan, Anson Dinh and copyedited by Rebecca Dang. Special thank you to Kia Dullemond for creating the How to Minimize Bleeding infographic.