The Clinical Scenario

A 35-year-old professor presents to the emergency department with marked dyspnea. He reports a history of asthma, for which he takes salbutamol, which is his only medication. Over the past 3 years, he has been coughing and wheezing with increasing severity. He has been using his inhaler every two hours with minimal effect. En route to the ED, EMS administered 10 mg of nebulised salbutamol. Upon arrival, the patient appears in extremis. You wonder if there is something you can do to avoid intubation.

[bg_faq_start]Differential diagnosis

“Not all that wheezes is asthma.” – unknown

Acute dyspnea or shortness of breath can be caused by many other conditions. A quick and dirty differential includes:

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Patients with COPD usually have a personal smoking history or a family history of α-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Occasionally a provisional diagnosis of COPD is first made on presentation to the ED, but more commonly these patients have already been diagnosed with chronic bronchitis or emphysema through pulmonary function testing. Most patients will have visited the ED before. The initial management of these patients is similar to the management of patients with asthma, but these patients are more likely to require antibiotic treatment for an acute exacerbation.1 In both these patients and asthmatics, the clinician must be careful to rule out pneumothorax, as both populations may have friable lung tissue that is prone to disruption.

- Congestive Heart Failure (CHF): Patients with an acute exacerbation of congestive heart failure sometimes present with a “cardiac wheeze”, which can be indistinguishable from the wheeze of asthma. Important additional symptoms that point to a diagnosis of CHF include orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, pedal oedema, elevated jugular venous pulsation (JVP), and a gallop heart rhythm (presence of S3 sound and sometimes an S4).2

- Anaphylaxis: Wheeze may be a prominent component of anaphylaxis. These patients generally present with associated symptoms, which may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, urticarial rash, or angioedema. It is important to differentiate between anaphylaxis and asthma because early intubation in rapidly-progressing and recalcitrant anaphylaxis may be necessary, as it can become difficult to intubate these patients as airway oedema progresses. On the other hand, intubation is delayed as long as possible for asthmatic patients.3

- Aspiration in children or the elderly or those with developmental delay: Inhalation of a foreign body, secretions, or a mucous plug is of particular concern in children, the elderly, and patients with cognitive deficits or developmental delay. The wheeze of aspiration can often by differentiated from asthmatic wheeze by its nature; the wheeze of asthma is bilateral and usually end-expiratory, whereas foreign body wheeze tends to be unilateral, with a timing that can change. CXR may help further elucidate the presence of foreign body, particularly if the foreign body is radio-opaque or has caused collapse of a lung or lung segment.4

History and physical

The history and physical exam are essential in differentiating asthma from other diagnoses. Most patients with asthma will complain of shortness of breath. These patients may describe a productive or non-productive cough, and frequently report a preceding viral upper respiratory tract infection. Those with mild asthma may describe shortness of breath, wheeze on exertion, or an occurrence during certain seasons. Those with severe asthma may describe more frequent wheeze, shortness of breath, or cough, and may have a history of hospitalisation for asthma treatment.5

A modified history may be necessary with patients who are unable to speak or answer with more than one or two words. Using open-ended questions in these cases may be inefficient until after these patients have been initially managed.

On physical exam, patients with asthma exacerbation usually have a detectable wheeze (unless the exacerbation is severe, and the patient is no longer moving air). In younger adults, it may be difficult to differentiate moderate to severe cases of asthma, as they tend to compensate fairly well. Children, however, may show signs of increased work of breathing, such as nasal flare, in-drawing, or tripod positioning.

The role of peak expiratory flow and spirometry

Measurement of peak expiratory flow (PEF) can be done at multiple points during an ED visit: at initial presentation, before and after treatment, and prior to discharge. Spirometry measurements can help differentiate patients, especially if an improvement is observed upon treatment. A PEF measurement that improves more than 15% after bronchodilators is diagnostic of asthma. Spirometry at the end of the visit can help in determining disposition; patients with unsatisfactory response to treatment may require specialist consultation and admission, while those with good response may be safe for discharge home with outpatient follow-up.6

Breadth of presentation of asthma

| Symptoms | Symptom Control with β2-agonists | Wheeze | |

| Mild | exertional dyspnea nocturnal symptoms cough | respond well | frequent wheezing, usually end-expiratory |

| Moderate | dyspnea at rest congestion chest tightness increased nocturnal symptoms | partially relieved; requires more frequent usage than q4h | constant wheeze, possibly during both inspiration and expiration |

| Severe | look obviously dyspneic sick | may have to self-medicate frequently in order to reach ED | decreased or absent breath sounds with decreased wheezing |

| Status asthmaticus/life-threatening | limited air movement, altered mental status fatigue | no response | silent, no wheezing |

Cardinal features of near fatal asthma include hypoxia, hypercapnia, severe agitation, limited air movement on auscultation, absence of wheezing, nasal flaring, accessory muscle use, tripod positioning, cyanosis, altered mental status, and fatigue.5

Patients with life-threatening asthma have a “silent” chest with no wheezing. This is due to the lack of air flow into the lungs due to obstruction; there is not enough air movement to induce wheezing.

Risk factors for death from asthma7

- Previous severe exacerbations

- 2 or more hospitalizations for asthma in the past year

- 3 or more ED visits in the past year

- Hospitalization or an ED visit for asthma in the past month

- Use of and entire metered dose inhaler canister within the preceding month

- Current use, or recent cessation of, corticosteroids

- Difficulty perceiving asthma symptoms (especially in patients with developmental delay, psychiatric illness, or cognitive impairment)

- Illicit drug use (especially insufflated or smoked)

- Lower socioeconomic status or inner-city residence

- Medical comorbidities

Workup of the asthmatic patient

- Chest X-ray (CXR): Use of CXR is not routine in asthma exacerbation, but it can be used to rule out alternative or associated diagnoses, such as pneumonia or pneumothorax.8

- Laboratory investigations: Blood work can be used to rule out other diagnoses, as in the case of troponin for ACS or d-dimer for pulmonary embolus, or to determine severity of disease, as in the case of blood gases. Generally speaking, venous blood gases (VBG) are less painful and invasive than arterial blood gases (ABG) and can be useful for following paCO2 levels, which increase as patients decompensate and cannot expel CO2.9

The management and treatment of asthma in the ED

Treatment of asthma includes β2-agonists, anticholinergics, corticosteroids and magnesium sulphate.

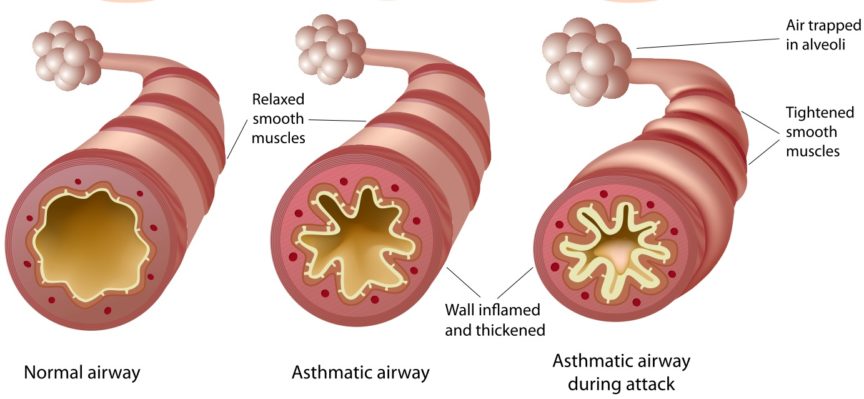

- β2-agonists: The most commonly used short-acting β2-agonist is salbutamol/albuterol (Ventolin). β2-agonist medications cause vasodilation of smooth muscle, promoting relaxation of bronchioles. Adrenergic side effects include nervousness, tremor, headache, hypertension, palpitations, tachycardia, and temporary hypokalemia. In patients who can coordinate breaths, metered dose inhalation with a spacer at 4-8 puffs every 20 minutes is just as effective as nebulised treatment; in those with severe exacerbations, continuous nebulised treatment with 2.5 mg of salbutamol may be necessary. 5,10,11

- Anticholinergics: Ipratropium bromide (Atrovent) is the most commonly used anticholinergic in asthma exacerbation. Anticholinergic medications dry up the excessive secretions present in asthma exacerbation. Three metered dose treatments of 4-8 puffs every 20 minutes seems to be useful alongside salbutamol for moderate to severe asthma exacerbations. In those patients who cannot coordinate breaths, 0.5 mg of ipratropium bromide can be nebulised alongside salbutamol.12

- Steroids: Oral or inhaled corticosteroids may reduce airway inflammation in a delayed manner and may help patients avoid admission and repeat visits. In patients who are able to take medications by mouth, 50 mg of prednisone or 0.6 mg/kg of dexamethasone (to a maximum of 18mg) may be given. Patients who are not able to take oral medications may benefit from intravenous solumedrol. Patients leaving hospital after an asthma exacerbation may benefit from inhaled corticosteroids, such as fluticasone (Flovent), as maintenance therapy.13

- Magnesium sulphate: Magnesium has been shown to have a role in smooth muscle relaxation, and intravenous magnesium (2g) may increase the chances of successful discharge home in moderate to severe exacerbations.14

- Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation: Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) can help with avoiding intubation in asthmatic patients with severe exacerbations, especially those who have not satisfactorily responded to initial bronchodilator therapy.15

- Heliox: A mixture of helium and oxygen theoretically increases laminar flow in narrow airways and may facilitate gas exchange.16

- Ketamine: The use of ketamine in asthmatic patients is highly controversial. Its bronchodilating properties may help in avoiding intubation if done as part of a delayed sequence intubation protocol, but there are concerns about increased respiratory secretions with ketamine treatment.5

- Epinephrine: This may be useful in haemodynamically unstable patients with refractory asthma exacerbation.5

Patients with acute asthma exacerbation require frequent reassessment. On reassessment, physically examination findings that suggest improvement include decreasing distress, improved respiratory rate, oxygen saturation of at least 94%, improving serial VBGs, and improved PEF.

[bg_faq_end]Case Review

The patient presents with a history of asthma and is not responding to β2-agonist use, indicating at least moderate asthma exacerbation. After ruling out other possible causes of respiratory distress, you decide to continue with β2-agonists, with the addition of oral corticosteroid (prednisone). You plan to add magnesium sulphate or non-invasive positive airway pressure if initial treatment fails, with an ultimate plan to use ketamine for delayed sequence intubation should intubation become unavoidable.

A summary infographic has been created by Kelly Lien & Dr. Alvin Chin below: