All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

CanMEDS Roles addressed: Medical Expert, Communicator, Leader

Case Description

You are a resident physician rotating through the ICU. You’ve been taking care of a 32-year-old woman who sustained injuries in a high-speed motor vehicle collision two days ago. She is now stable and extubated in the ICU. Her hemoglobin has been stable in the 80s since arriving in the ICU but today hemoglobin is 75 g/L.

Her complete blood count (CBC) also demonstrates a white blood cell (WBC) count of 10.9 x 109/L and platelet count of 135 x 109/L – both of which are slowly normalizing. Reticulocyte count is 45.

There are no signs of bleeding clinically or on ultrasound examination of the abdomen. There is no laboratory evidence of hemolysis.

You suspect the patient may be unable to produce adequate RBCs due to inflammation from her injuries and operation. To be safe you send investigations to check nutritional parameters and start folic acid empirically.

The patient complains of fatigue and you decide a blood transfusion is indicated. The situation is no longer emergent, and the patient will have to be consented for a blood transfusion.

Understanding the risks of blood transfusions

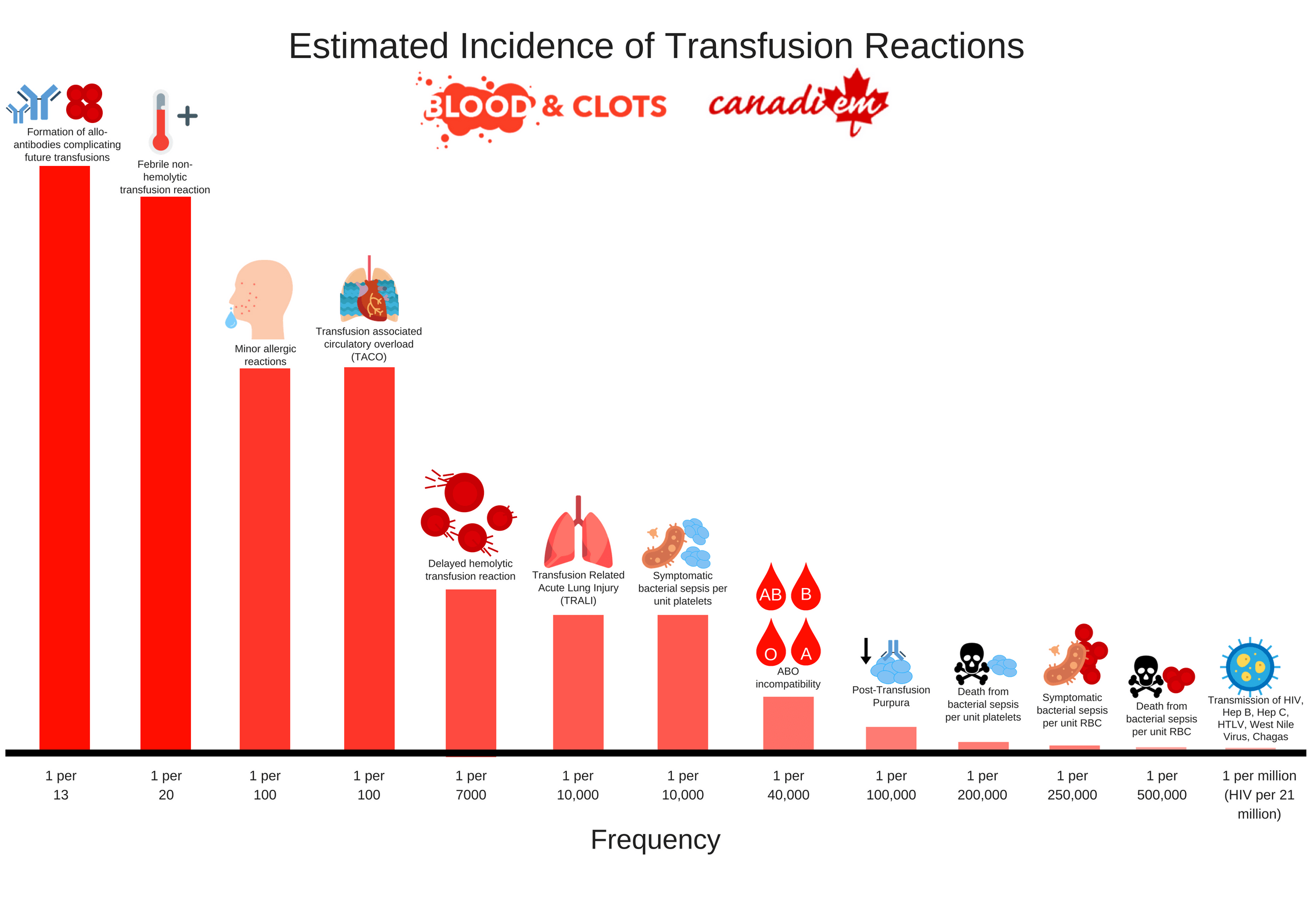

Red blood cell transfusions carry certain risks. Ensure that there are no safer alternatives to blood transfusion prior to engaging your patient for consent. When consenting a patient, you will want to include reactions that are common and meaningful to your patient, as well as uncommon but potentially serious risks (below).

Infographic 1: Estimated Incidence of Transfusion Reactions

You obtain consent for blood transfusion from your patient by briefly describing the risks of transfusion and then explaining the potential benefits. You place an order for a single unit of packed red blood cells to be transfused over two hours.

You obtain consent for blood transfusion from your patient by briefly describing the risks of transfusion and then explaining the potential benefits. You place an order for a single unit of packed red blood cells to be transfused over two hours.

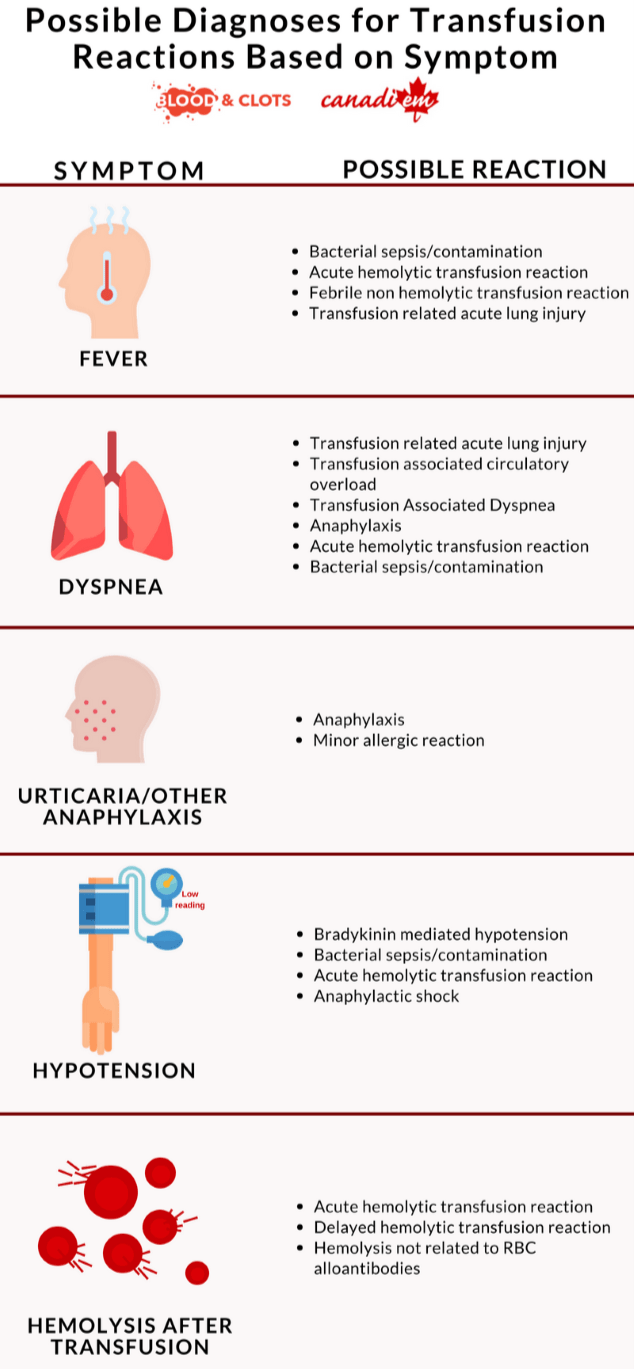

Ninety minutes into the transfusion you are called back to the bedside due to concerns regarding shortness of breath. In this case we will focus on dyspnea, but health practitioners should also have an approach to fever, hypotension, or pain during a transfusion as these could indicate a serious reaction (below).

Infographic 2: Possible Diagnoses for Transfusion Reactions Based on Predominant Symptom

Upon arriving at the bedside you note the patient’s respiratory rate and work of breathing have increased. Dyspnea in a patient receiving transfusion could indicate a transfusion reaction and you immediately take the following steps:

Step 1· Immediately stop the transfusion

Step 2· Assess the patient for other possible signs of transfusion reaction including fever, chest pain, back pain, itching, angioedema; measure vital signs; perform a limited physical examination guided by symptoms.

Step 3· Resuscitate & Support – Apply oxygen, initiate fluids, and other supportive care as required

Step 4· STAT Chest X-ray if true dyspnea or other concerning features

Step 5· Check the product labels to ensure the correct product has been given to the right patient

Step 6· Follow local procedures for informing the transfusion medicine lab about suspected transfusion reaction. They may be able to help with advice and management. This is particularly important if you discover the patient has received a different patient’s blood through clerical error – the other patient may also be receiving the wrong blood!

After you’ve completed these steps it’s important to consider the possible causes of dyspnea in a patient being transfused. These include Anaphylaxis, TRALI, and TACO. Chart 1 summarizes features that will help distinguish these reactions separately.

| Cause of Dyspnea in a transfusion recipient | Description | Management |

Anaphylaxis From 1/20,000 to 1/50,000 transfusions. | Usually occurs immediately at the start of a transfusion. Typically accompanied by other anaphylactoid symptoms including airway compromise via angioedema, dyspnea and wheezing, hypotension, urticaria, and flushing. | Stop the transfusion and institute standard treatments for anaphylaxis . Consider early administration of intramuscular epinephrine, intravenous fluid, and bronchodilators. |

TRALI: Transfusion-related acute lung injury Around 1/5000 transfusions. | Characterized by bilateral lung infiltrates and hypoxemia during transfusion or within 6 hours after. Usually occurs in the absence signs of fluid overload and within the first two hours of transfusion. Symptoms and signs include dyspnea, hypoxemia, hypotension, and fever. Cases typically resolve within 24-72 hours with supportive care. Other sources of hypoxemia should be managed appropriately. Steroids and diuretics are not directly useful (but can be used to treat concomitant causes of hypoxemia). | Stop transfusion and treat supportively. Many patients with TRALI will require supplemental oxygen and ventilator support. Patients with TRALI should be managed with lung protective ventilation similar to ARDS. Reporting TRALI is critical to preventing future cases. Testing can be performed to identify and defer blood donors implicated in the development of TRALI. |

TACO: Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload The most common cause of death from transfusion. Estimates of frequency vary widely from 8/100 to 1/700 . | Presentations include dyspnea, orthopnea, hypoxemia, tachycardia, and hypertension. Clinical exam and imaging will demonstrate volume overload. The use of loop diuretics prior to transfusion should be individualized depending on patient risk of volume overload. The pre-test probability of TACO may be estimated based on the presence of risk factors for TACO including:

| TACO can be managed similarly to acute decompensated heart failure with supplemental oxygen and intravenous furosemide. Consider non-invasive positive pressure ventilation or intubation in severe cases. |

You conclude anaphylaxis is unlikely on our patient due to the delayed onset and lack of other anaphylactoid symptoms. TACO and TRALI can be difficult to differentiate in patients with hypoxemia following transfusion. You notice the patient is hypertensive compared to her baseline (152/88) and has features of volume overload. Going back through the records you note that the patient’s fluid balance over the last 24 hours is +3L. A fluid status exam now shows JVP at 5 cm and rales at the lung bases bilaterally. The patient now requires 2L of supplemental O2 to maintain an oxygen saturation >90%. TACO is much more common than TRALI. Hypertension and features of volume overload on examination strongly suggest a diagnosis of TACO, and hypotension or fever may suggest a diagnosis of TRALI.

You suspect that the patient in this case most likely has TACO and treat with intravenous furosemide.

TACO is a common and potentially fatal complication of transfusion. In the non-emergent setting patients receiving transfusions should always be assessed for volume status and risk factors for TACO prior to transfusion. If risk factors are present intravenous furosemide should be given prior to transfusion. You consider the following measures to prevent TACO during non-emergent transfusions in the future:

- Consider the necessity of transfusion and also consider other methods of raising hemoglobin

- Physical exam for signs of volume overload before every transfusion as part of consent and risk assessment

- Consider the risk factors for TACO and give pre-emptive furosemide if these are present

- Only transfuse a single unit of blood at a time when possible

- Minimize concurrent administration of other IV fluids during transfusion

- Conservative infusion rates minimize the risk of TACO. Include an infusion time or rate in your orders and specify blood to be given more slowly (over 3-3.5 hours) in patients at risk of TACO.

Case Conclusion

You appropriately recognize TACO and treat with intravenous furosemide. Because the patient is young and does not have pre-existing cardiac or renal disease she responds appropriately to diuresis. Three hours later the patient is off oxygen and her dyspnea has improved.

You sigh with relief, but recall at a recent teaching session that your attending had warned you that not all patients are able to recover from TACO so easily. You make a mental note to consider pre-transfusion diuretic therapy for all non-emergent transfusions in the future by considering risk factors for TACO and signs of volume overload on physical exam. The patient remains in the ICU overnight for monitoring but is in stable condition for transfer to the ward the following morning.

Main Messages

- Blood transfusions carry risk including the risk of death. Consider other options for raising hemoglobin wherever possible.

- Fever, hypotension, or dyspnea in a transfused patient could indicate an emergency. Stop the transfusion and assess the patient if these signs are present. For dyspnea consider TRALI, TACO, and anaphylaxis.

- TACO is one of the most common causes of death from transfusion. Assess patients for Lasix pre-transfusion by considering risk factors and a current volume status exam.

Additional Resources

Alam A, Lin Y, Lima A, Hansen M, Callum JL. The prevention of transfusion-associated circulatory overload. Transfus Med Rev. 2013;27(2):105-12.

Tseng E, Spradbrow J, Cao X, Callum J, Lin Y. An order set and checklist improve physician transfusion ordering practices to mitigate the risk of transfusion-associated circulatory overload. Transfus Med. 2016;26(2):104-10

All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

This post was reviewed by Mark Woodcroft, Teresa Chan and copyedited by Rebecca Dang.