Introducing the Teaching That Counts Infographic Series

Teaching in the Emergency Department is essential for developing budding learners that will eventually be treating our patients. Not only do we have a duty to teach, but teaching also allows even seasoned physicians to crystallize their own knowledge and reflect on their current practice.

Physicians teach in the emergency department all the time, but in a specialty with an already enormous cognitive load, it can be tough to stay up-to-date with evidence-based teaching practices. This is especially true for less-experienced teachers such as residents and new graduates, who are transitioning into practice and were learners themselves not long ago.

The CanadiEM Teaching That Counts Infographic Series takes the current research and evidence on how to teach well in the emergency department, and distills it down into bite-sized chunks that are rapidly digestible and memorable. The goal of the infographic series is to provide evidence-based teaching tools, topics and tips that can be referenced by educators while teaching on shift, ultimately serving as a resource for physicians looking to develop, refresh, or refine their teaching practice.

These infographics were initially posted in the Kitchener-Waterloo hospitals and Joseph-Brant Hospital in Burlington. We received positive feedback on them and it became clear that there is a need for resources to guide emergency physicians’ teaching, that is easily accessible on shift. The infographic series spread amongst physicians in the McMaster region and is now posted in eight departments in the area, and counting.

Feel free to post the infographics in your department to give physicians a quick reference guide for how to teach on shift and make it count!

This series was created by Dr. Krista Dowhos and Dr. Alim Nagji.

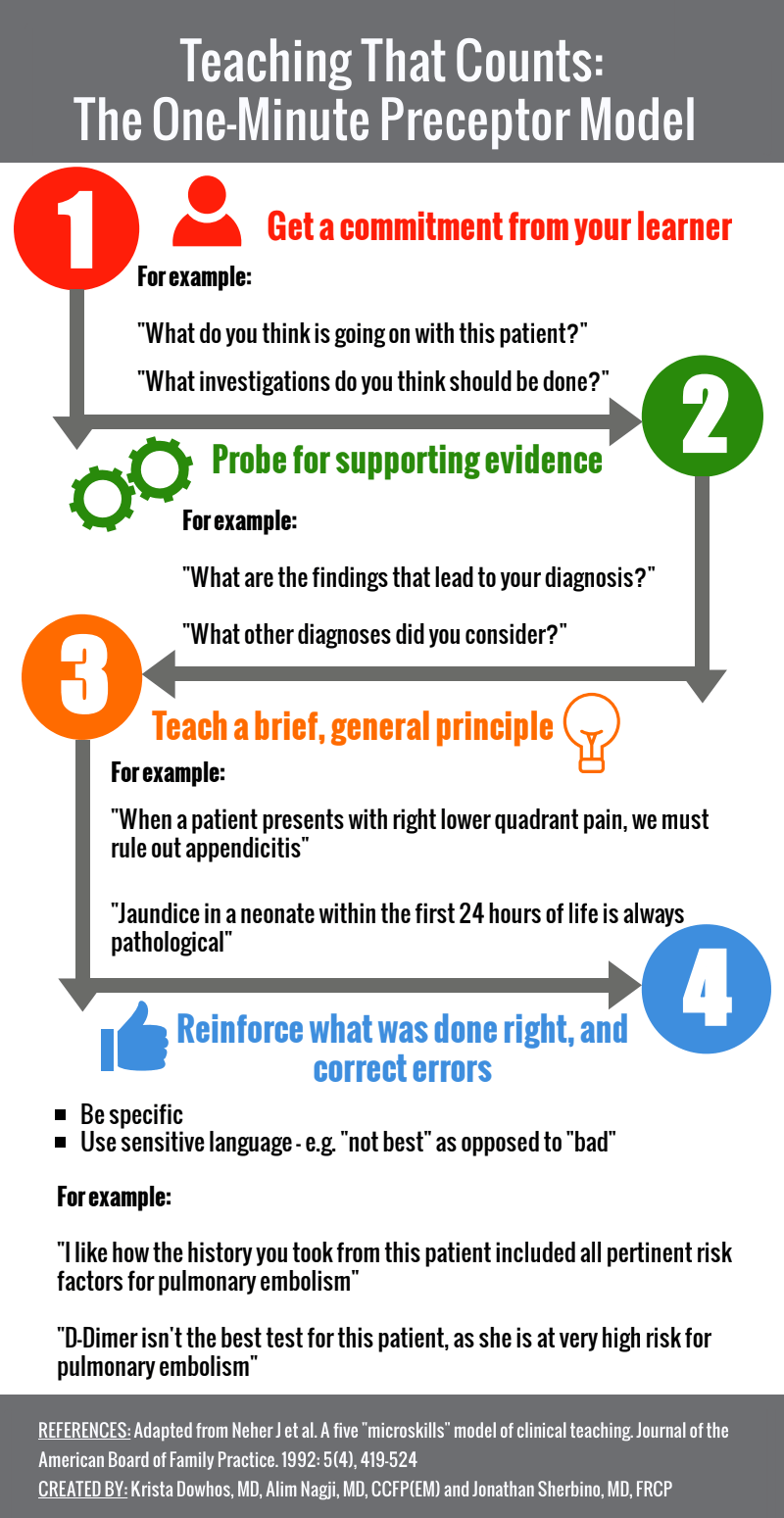

The One-Minute Preceptor Model

The one-minute preceptor model (OMP) was first described in Family Medicine Education literature by Neher et al. in 19921. Since then, it has become one of the cornerstones for professional development in clinical teaching and has been adapted to a variety of medical specialties, including emergency medicine2–5.

Four Steps to the OMP:

- Get a commitment from the learner

- Probe the learner for what led them to their differential diagnosis or plan

- Teaching a general principle

- Reinforce what was done right and correct errors

By getting a commitment from the learner early on in the teaching encounter, it helps the learner feel responsible for the patient’s care and engages them in a collaborative learning process4. This can be a commitment to a diagnosis, work-up or management plan. Next, the preceptor probes the learner for how they arrived at their decision. For example, if the learner thinks the patient may have a pulmonary embolism, ask “and what risk factors does this patient have for developing a PE?”. If the learner says they want to order a d-dimer, ask them “and why would you choose a d-dimer for this patient instead of going straight to a CT-PA?”. Understanding the learner’s thought process allows the preceptor to identify knowledge gaps (and prevent teaching them something they already know or aren’t ready to learn), which will guide step 3 – teaching a general principle.

This principle should be brief and translatable to a broad number of cases. For example, “d-dimer is a useful test to rule out PE in low-risk patients and is not best used in patients at high-risk for PE”. Then, reinforce what was done right by saying, for example, “you did a great job of determining the patient’s risk factors for PE, such as an active cancer, previous DVT, and recent surgery”. Lastly, give the learner something to work on by correcting any errors you identified during the teaching encounter. For this encounter, you could say, “for this patient, I think we should instead go straight to a CT-PA instead of ordering a d-dimer, as PE is very likely given her hypoxia, tachycardia, and risk factors. Does that make sense to you?” Alternatively, you could ask the learner what they would do differently next time, based on your discussion, and he or she may be able to correct the error on their own.

Since the development of the one minute preceptor model, it has been evaluated in experimental education studies and has become an evidence-based teaching tool that can be easily implemented on shift in the Emergency Department due to its efficiency3–5.

- 1.Neher J, Gordon K, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5(4):419-424. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1496899.

- 2.Rogers R, Mattu A, Winters M, Martinez J, Mulligan T. Practical Teaching in Emergency Medicine. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012.

- 3.Furney S, Orsini A, Orsetti K, Stern D, Gruppen L, Irby D. Teaching the one-minute preceptor. A randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):620-624. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11556943.

- 4.Wald DA. Teaching Techniques in the Clinical Setting: the Emergency Medicine Perspective. Academic Emergency Medicine. October 2004:1028.e1-1028.e8. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.002

- 5.Aagaard E, Teherani A, Irby D. Effectiveness of the one-minute preceptor model for diagnosing the patient and the learner: proof of concept. Acad Med. 2004;79(1):42-49. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14690996.