You are dispatched lights and sirens for Jennifer, a 52-year-old female complaining of “the worst headache of my life”. She recalls running on a treadmill then feeling like she had been struck in the back of the head by a clap of thunder. She then proceeded to have a witnessed two-minute episode of syncope. On arrival you find Jennifer coming out of the bathroom where she was just vomiting. As you are getting her on your stretcher she begins to seize; you expedite transport and bring the patient’s partner Susan with you.

[bg_faq_start]About Sirens to Scrubs

Sirens to Scrubs was created with the goal of helping to bridge the disconnect between pre-hospital and in-hospital care of emergency patients. The series offers in-hospital providers a glimpse into the challenges and scope of practice of out-of-hospital care while providing pre-hospital providers with an opportunity to learn about the diagnostic pathways and ED management of common (or not-so-common) clinical presentations. By opening this dialogue, we hope that these new perspectives will be translated into practice to create a smoother, more efficient, and overall positive transition for patients as they pass through the ED doors.

[bg_faq_end]Objectives

- What are some common signs and symptoms of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)?

- How can pre-hospital providers manage suspected SAH?

- How is SAH is diagnosed and managed in the ED?

Susan asks you what you think is happening to Jennifer

You recall that the “worst headache of my life” and “thunderclap headache” are often descriptors for a subarachnoid hemorrhage – bleeding into the space between the arachnoid and the pia mater of the brain, where all the blood supply for the brain runs. You also remember that while nearly everyone suffering from SAH will use these descriptors, only 1 in 10 patients with these symptoms will actually be diagnosed with SAH. You also recall that patients with SAH can also have syncopal episodes, seizures, neck stiffness and focal neural deficits like vision changes with this disease. Often, people will recall having a similar, although less severe and time-limited, headache in the days or weeks prior to the main event (called a “sentinel bleed”).

You tell Susan that about 85% of these bleeding events are due to a saccular or “berry” aneurysm; an outpouching of the blood vessels most often found at the base of the brain in the Circle of Willis. They occur slightly more frequently in women, with an average age of 49-55 and often as a result of long-standing hypertension, and some genetic diseases like polycystic kidney disease and Marfan’s syndrome can increase your risk.1

“Do you think it could be anything less serious?”

You think a moment and list off a few differential diagnoses, like meningitis, or a migraine, that can also present with some of these symptoms, but you tell Jennifer that SAH is often misdiagnosed in the community and any delay to treatment can have devastating consequences.

So as to not frighten Susan, you keep to yourself your concern that despite being a rare cause of stroke, about 2-7%, SAH represents about 25% of the years of life lost for all strokes, and that there is a case fatality rate of between 32 and 67%, with 50% dead at 1 month, and 50% alive but with serious disability. You begin to see that Jennifer is in a lot of danger.23

What can you do for Jennifer on the way to the hospital?

As Jennifer’s seizure continues you confirm that she is not hypoglycaemic and administer intranasal midazolam. The seizure stops and you reassess, insuring the ABCs are accounted for and an IV is established. She remains very altered, but if Jennifer was awake and complaining of severe pain or nausea, treatment with analgesics (including opioids) or anti-emetics would be indicated. You follow her vital signs to keep an eye out for Cushing’s triad: bradycardia, widening pulse pressure, and irregular breathing, that would tell you that the intracranial pressure is increasing.

You consider the risk and benefits of intubating Jennifer on the way to the hospital

Risks:

- Most paramedics don’t carry induction agents (i.e. etomidate, ketamine, propofol) or paralytic agents (i.e. succinylcholine or rocuronium). These medications increase your likelihood of intubation success and decrease some of the associated risks

- Many EMS services don’t offer backup airway options (i.e. video laryngoscopy, surgical airway)

- Often only one crew member is skilled in intubation, meaning there is no backup operator

- Ability to optimally position your patient, and yourself, is very limited

- Providers are often alone in the back of the ambulance, without additional hands to help with the intubation by watching vital signs, providing BURP, handing you supplies, or administering pre- or peri-intubation medications

- Performing skills in the back of a moving ambulance always requires an impressive level of technique, balance, and physical coordination

- It is also very difficult to respond to peri-intubation complications, such as vomiting or hypotension, when you’re alone in the back of a moving ambulance

- Post-intubation sedation is a challenge without IV infusion pumps

- Without a ventilator, volume and pressure of manual ventilations are imprecise, require continuous provider attention (to the exclusion of other tasks), and can become very exhausting when transport times are very long

All of these factors make pre-hospital intubations an exceptionally high-risk procedure.

Benefits:

- Ability to titrate EtCO2 to 35mmHg if Jennifer starts to show signs of herniation (remember, we don’t hyperventilate these patients anymore, but we do target the lower end of normal EtCO2)

- Protects the airway if she begins to vomit again

- Superior oxygen delivery, especially if Jennifer has already aspirated

On arrival at the receiving hospital you ask the EM resident what will be done for Jennifer now

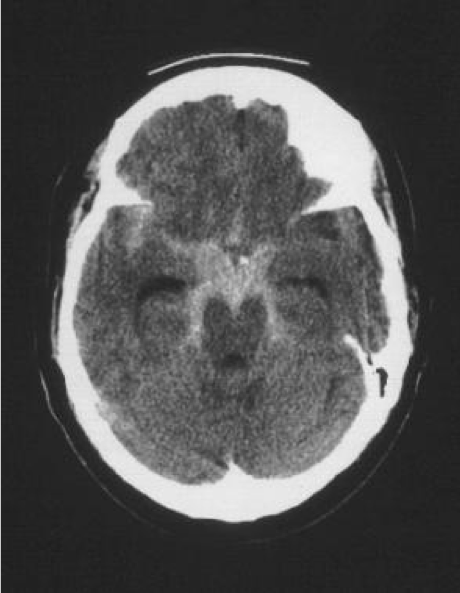

With Jennifer having such clear-cut symptoms of SAH, the team will do some bloodwork and order a CT head to check for obvious bleeding. The resident is confident that the CT will find a bleed, as CT will find a subarachnoid hemorrhage nearly 100% of the time within 6h of the onset of symptoms. However, when suspicion is high for SAH and the CT is normal, when symptoms developed >6h prior to presentation, or in other specific circumstances, a lumbar puncture (“spinal tap”) is performed to look for blood, or the products of hemoglobin breakdown (“xanthochromia”) in the cerebral spinal fluid.

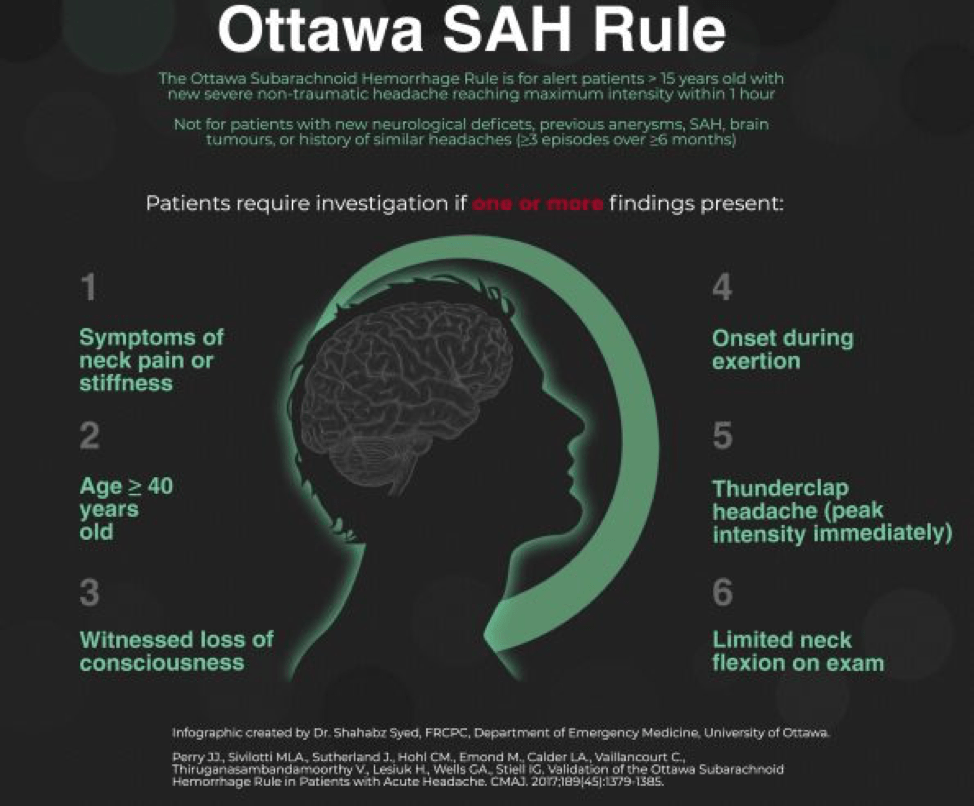

In a patient that doesn’t have such obvious symptoms, the Ottawa SAH Rule can help guide decision-making. You’ll notice that many of the components of the rule are also on the list of red-flag symptoms for headache, which you can read about in this great article. However, the rule should be used with caution as it has not yet been fully validated across a broad enough range of populations yet to be considered prime-time. You can read more about how to use the Ottawa SAH Rule here or here.

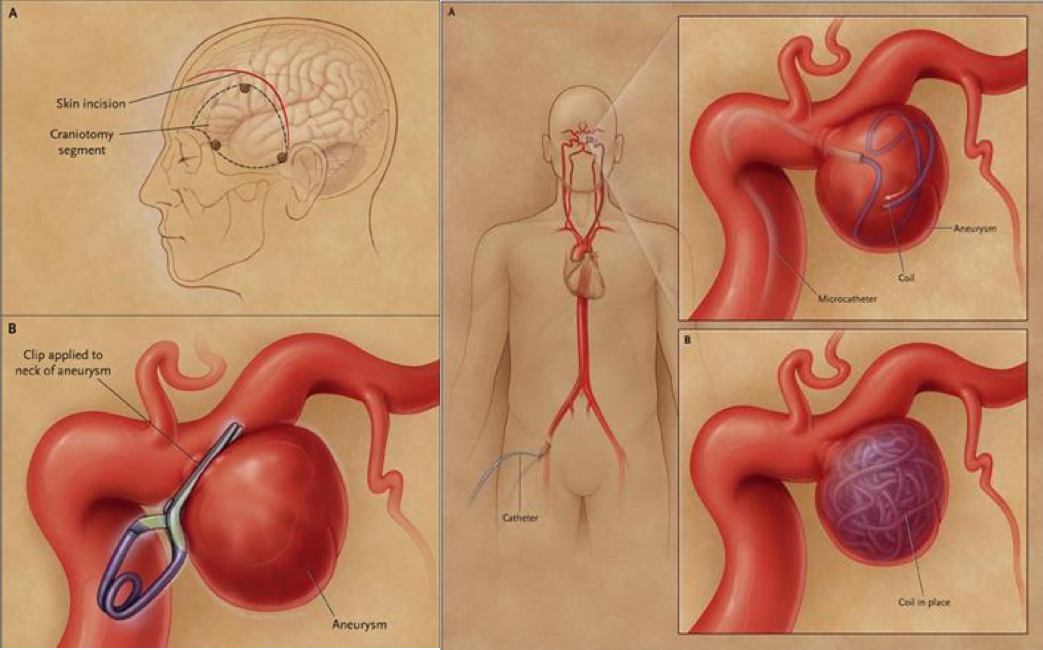

The EM resident adds that if this turns out to be an SAH, Jennifer will go in for a cerebral catheter angiography to find the most likely cause of the bleeding. If it is the berry aneurysm as we suspect, it will either be coiled or clipped to stop the bleeding.

What does “coiled or clipped” mean?

The resident explains that Jennifer will either get the aneurysm cut off with a surgical clip to close off the pouch, or a wire will be inserted by interventional radiologythat will fill up the pouch and eventually clot and scar off. Sometimes a stent is placed in especially wide necked aneurysms to facilitate repair. The latter is preferred all else being equal as it does not require opening the skull.

Medscape – on the left, a surgical clip, on the right, a coiling through interventional radiology.

As the resident finishes her explanation. The Jennifer returns from CT and the following image is obtained, showing obvious bleeding into the subarachnoid space around the base of the brain. The EM resident calls Neurosurgery to arrange cerebral angiography and admission.

Medscape – SAH in the basal cisterns.

As you are finishing your paperwork, you notice Susan still sitting in the chairs waiting to hear about Jennifer’s prognosis and you ask the attending EM physician what Jennifer’s most likely outcome will be

The physician tells you that most often the aneurysm is in the anterior circulation of the Circle of Willis, near a bifurcation point. In Jennifer’s case, it will turn out that the aneurysm is at the junction of the right internal carotid and the anterior communicating artery. They also tell you that the most common complications from an SAH is rebleeding and vasospasm, and she will spend many days in the ICU as they struggle to control blood pressure and blood chemistry and try to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure.

You finish your paperwork and get back on the road, happy that you were able to recognize the symptoms of SAH and get Jennifer to the hospital to definitive care.

That’s it! If you have any questions, thoughts, alternative perspectives, or requests for future topics, feel free to comments below or send me an email at [email protected]. Please keep in mind that, although I will do my best to publish information that is accurate across Canada, there will inevitably be some regional differences in both pre-hospital and in-hospital management of emergency patients. As a paramedic and Emergency Medicine resident in Ontario, some posts may wind-up being somewhat Ontario-centric, hence, I encourage anyone whose experiences differ from mine to contribute to the conversation by commenting below.