You and your partner are called to a private residence for Francesca, a 50-year-old woman who feels ‘generally unwell.’ Simple, right?

[bg_faq_start]About Sirens to Scrubs

Sirens to Scrubs was created with the goal of helping to bridge the disconnect between pre-hospital and in-hospital care of emergency patients. The series offers in-hospital providers a glimpse into the challenges and scope of practice of out-of-hospital care while providing pre-hospital providers with an opportunity to learn about the diagnostic pathways and ED management of common (or not-so-common) clinical presentations. By opening this dialogue, we hope that these new perspectives will be translated into practice to create a smoother, more efficient, and overall positive transition for patients as they pass through the ED doors.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]Preliminary Musings

First off, I apologize for adding yet another post to your reading list about COVID-19. With the enormous presence of social media, there has been an abundance of information being blasted at us from all directions. In some ways, this is preferred over a lack of information, but it introduces different challenges. I paused when I considered whether to add more information to the whirlpool, but the anxieties, misinformation, and wealth of assumptions being masqueraded as facts in my EMS community led me to publish this article in my own semi-educated attempt to clear up some confusion – or at least offer some explanations for why such confusion exists.

Second, as with any COVID-19 information, everything in this piece needs to be taken with a grain of salt. COVID-19 is rapidly changing and its lifespan has been too short for in-depth, well-controlled studies to be performed. The information is ever-changing as more is learned.

Third, I apologize that I won’t be able to provide clear answers to your burning questions. In particular in Ontario (which this will be even more Ontario-centric than my other posts), I can’t make the Ministry of Health’s gray recommendations for paramedics any more black-and-white.

Fourth, this article is even more paramedic-centric than usual. In many circumstances, pre-hospital and in-hospital medicine has a lot of overlap and a lot to learn from each other. But working amidst a pandemic probably isn’t one of those situations. Paramedics face unique challenges requiring creative solutions.

Lastly, this is a longer article than I usually post. I considered separating it into two parts, but by the time the second part came out I would essentially need to rewrite it with all new information, and that sounded like too much work.

[bg_faq_end]Objectives:

- Review the fundamentals of infection control precautions, especially as they apply to paramedics

- Discuss COVID-19 as it relates to prehospital care

How are patients screened for COVID-19 during the call-taking process to prepare paramedics prior to their arrival?

Patients have always been screened for febrile illnesses when they call 911, either through questions built into the pre-determined dispatch questions or through the use of a screening tool, when appropriate (i.e. ebola). Since January 20, 2020, the Ontario ambulance communications officers have been screening for COVID-19 by asking the caller a series of pre-determined questions. The screening tool, which has been created by Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC), has changed as the disease pattern has morphed from being primarily travel-spread to being community-spread. The first version of this tool was very restrictive – requiring both symptoms and a clear source of infection (either travel or direct contact with a traveller or COVID-19-positive patient). As of April 2, the tool has gotten much broader. This is to account for several changes in the virus patterns:

1) a large percentage of virus transmission is occurring in the community, so travel nor direct contact with a confirmed COVID-19 patient is required any more to screen positive in the presence of respiratory symptoms.

2) Asymptomatic transmission is occurring, so symptoms are no longer required if high-risk contact has occurred (either travel or contact with a COVID-19 patient).

3) Testing resources have been quite limited in Canada, so we haven’t been able to test as many potential patients as we would like to. This means people may have COVID-19 and not know it; for this reason, close contact with anyone with respiratory symptoms is considered a high-risk contact. Now, close contact isn’t defined in this tool, but taken from other definitions of this can include:

- Caring for a patient (either as a healthcare professional or caregiver) without consistent use of PPE

- Living in the same home

- Prolonged contact within 2m of a symptomatic patient (again, ‘prolonged’ is a vague term that has been defined elsewhere as 15min)

- Direct contact with respiratory secretions from a symptomatic patient while not wearing PPE

- Sharing the same confined space in close proximity with a symptomatic patient for > 1 hour

On further questioning EMS dispatch learns that Francesca feeling feverish, short of breath, and coughing. Her husband, Jimmy, recently returned from Italy and has developed a cough over the last week.

Dispatchers are now advising callers to meet paramedics at the front of their house, to stand 2m back until paramedics can complete their screening questions and apply PPE, and to apply a mask if they’ve been advised to wear one. Callers are also asked to have family members remain 2m back from paramedics while doing assessments on their loved ones when possible.

How should paramedics protect themselves when they arrive at Francesca’s house?

Paramedics are encouraged to perform their own screening assessment from the doorway upon arrival. Unfortunately, there have been many instances where paramedics have arrived scene to a call that screened ‘COVID-19-negative’ by dispatch only to find a patient or loved one with high-risk contact or travel. In my optimistic view of the world this is likely due to several reasons, including language barriers, stress leading to misunderstanding of dispatch questions, or a dynamic call situation (i.e. an additional person has arrived scene that screens positive). If the household screens positive at this point it is important to don PPE prior to patient contact. Of course, this will be challenging in a high-acuity setting, but it is important to protect ourselves. In this situation if family is present they can be directed to initiate CPR or other interventions while you get yourselves ready.

Where the call details indicate a COVID-19-positive screen and a low-acuity (or highly-futile) situation, a single paramedic should approach the scene first while the driver remains near the front compartment of the vehicle ready to don their PPE if they are required.

What personal protective equipment should be used by healthcare providers, and paramedics in particular?

We’re going to go back to infection control basics here for a bit. Although we all learned this at some point, I think many of us had more pressing things to learn at the time so maybe didn’t pay too attention to the details. In addition, I think we have probably become complacent because we don’t perceive most pathogens as ‘scary’. So here we go:

There are several levels of infection control, each with their own PPE requirements (as well as environmental controls and other recommendations, which I won’t discuss).

Contact precautions

- This can be direct (touching an infected person) or indirect (touching an object that an infected person has touched)

- Hand hygiene + gloves + gown

Droplet precautions

- This level of precaution is required for patients with an infection that is suspected to be transmitted by large droplets

- Droplets are too large to travel far, usually less than 2m. They can be produced by talking, sneezing, coughing, or through many procedures

- Once again, this can be direct (a droplet flies at your and lands in your mouth, nose, or eye) or, more commonly, indirect (a droplet lands on an object, the virus remains viable until you touch that same object then touch your mouth, nose, or eyes). Depending on the pathogen and the type of surface, some microorganisms can remain viable for long periods of time

- Hand hygiene + gloves + procedure/surgical mask + eye protection (safety glasses or goggles, shield) when <2m from the patient

- Apply a surgical mask to the patient to minimize the pathogen particles that land on ambulance surfaces and objects

Droplet/contact precautions

- In reality, droplet precautions are rarely indicated without contact precautions. This is because of indirect droplet transmission. A gown allows any droplets that land on you to be disposed of, protecting you from picking up droplets from your uniform then eating that yum yum virus later with your pizza.

Enhanced droplet/contact precautions

- This is a unique form of droplet/contact precautions in which usual PPE is worn for most interactions with the patient

- An N95 is used in place of a procedure/surgical mask for aerosol generating medical procedures (described later)

- There are no usual microorganisms that require this level of precautions – it may be indicated for influenza (especially epidemic/pandemic strains) or SARS (and now, COVID-19)

Airborne precautions

- This level of precaution is required for patients with an infection that produces small particles that remain suspended in the environment for long periods of time and can travel with air currents, sometimes great distances

- Hand hygiene + gloves + N95

- Apply a surgical mask to the patient to minimize the pathogen particles that become suspended in the ambulance air

- Ensure the ambulance ventilation system is activated throughout the call and for a minimum of 5min afterward

Routine precautions

- This is a variable term that means different levels of PPE depending on the type of interaction you have with the patient. At a minimum, it includes hand hygiene. For paramedics, gloves should essentially be considered part of routine precautions, since we can assume that we’ll be coming into contact with some body fluid or contaminated object on each call.

- Other considerations may include:

- If you anticipate performing any procedures likely to produce secretions (coughing, sneezing, or airway procedures such as suctioning, ventilating, CPAP, intubation, needle thoracostomy, surgical airway, or nebulization) – add a procedure mask and eye protection

- If you anticipate your skin or uniform being exposed to body fluids – add a gown

- Your own health and level of immunity; if you suffer significant comorbidities or immunosuppression you may have a lower threshold for adding additional PPE to your patient interactions

Each disease-causing microorganism has been studied to determine how it is transmitted. However, paramedics specialize in working with the undifferentiated patient – we make decisions based on clinical syndromes rather than diagnoses (most of the time). For this reason, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has made recommendations regarding what level of precautions should be taken when certain symptoms are identified based on the most common etiologies. A comprehensive list can be found here, but a few of the pertinent presentations include;

- Respiratory illness, including colds, croup, febrile respiratory illnesses, influenza-like illnesses (runny nose, fever, sore throat, cough, myalgias) – droplet/contact

- Conjunctivitis – contact

- Draining wound (any skin infection with pus) – routine for anything contained by a dressing, contact if it can’t be contained by a dressing, droplet if an invasive group A streptococcal infection is suspected (i.e. the patient appears ‘sick’)

- Fever without an obvious source – routine for adults, contact for children

- Gastroenteritis (vomiting or diarrhea suspected to be infectious) – contact (routine is considered appropriate for continent patients with good hygiene)

- Meningitis/encephalitis (fever, headache, neck stiffness, photophobia, confusion, seizures) – droplet/contact

When are airborne precautions indicated?

We can see in the list above that airborne precautions aren’t required for most of our common clinical syndromes. This is because the microorganisms for which airborne precautions are indicated are actually so few. These essentially include:

- Tuberculosis

- Measles

- Varicella (chickenpox, shingles)

So, under normal (non-COVID-19) circumstances, when should paramedics use airborne precautions rather than droplet/contact? Well, the MOHLTC states that paramedics are unable to differentiate between droplet and airborne respiratory diseases and paramedics may use an N95 (in addition to the rest of droplet precautions) for any patient with respiratory illness. It doesn’t, however, state that this MUST be done and acknowledges that surgical masks must be carried on the ambulance and are adequate for protecting against pathogens that are transmitted through droplets. So how do I interpret this normally? For me, airborne precautions are indicated for:

- Tuberculosis: Persistent cough + risk factors for exposure to tuberculosis (travel, drug use, HIV, diagnosed tuberculosis, incarcerated, living in a shelter) +/- wasted/cachectic appearance +/- hemoptysis (tuberculosis) +/- fever

- Measles, varicella (chickenpox): Fever + rash (contact precautions are also indicated for chickenpox)

- Varicella (shingles): Painful rash (contact precautions are also indicated for shingles in specific circumstances, so it’s best just to use contact precautions for any suspected shingles)

Regardless of what you choose to do, remember that just wearing an N95 mask on its own protects you from only three of the hundreds of much more common respiratory viruses. It’s essential to add a gown and eye protection when respiratory illness is suspected.

That’s all very interesting, but we’re in a pandemic here! What should paramedics wear for suspected COVID-19 encounters? (and let’s be real, that’s most patients now)

When COVID-19 was first identified, Public Health Ontario (PHO) was recommending that N95 masks be used for contact with any potential COVID-19 patient. On March 25 recommendations were changed to ‘enhanced droplet/contact’ precautions (described above). Specifically, aerosol generating medical procedures that are relevant to paramedics are defined by PHO as:

- Endotracheal intubation

- CPR during airway management

- Suctioning (unless using a closed system)

- CPAP

- High-flow oxygen

The change in recommendations was based on epidemiological and scientific evidence that COVID-19 is not transmitted through airborne routes. This is in line with WHO and CDC recommendations. PHO further confirmed that these recommendations extend to first responders in an Evidence Brief published March 29 2020.

If you’re interested in reading about some of the discussions and studies surrounding the role of airborne versus enhanced droplet/contact precautions, here is a pretty decent article that outlines some of the considerations. I’m not going to pretend to be an expert about this. At best, I’m a semi-educated resident physician and paramedic. So my approach is to listen to the experts. Guidelines are produced in consultation with epidemiologists, infectious diseases physicians, scientists, and other people much, MUCH smarter than me, especially when they work in collaboration. If they tell me that I’m safe to wear a procedure/surgical mask (plus other droplet/contact precautions) and ask me to do this to preserve N95s for higher risk procedures then this is what I’m going to do. However, nothing is certain in life, least of all COVID-19, and I won’t be surprised if these recommendations do change back to preferred airborne precautions. If this happens I shall adapt and modify my practices. I think it’s extremely important to remember that everyone is doing their best to stop COVID-19 and keep us safe with the limited information that’s available at this early stage.

Fomites (objects in the environment that become contaminated and can be used as a vehicle for disease transmission) are another important source of spread for many pathogens. Interestingly, PHO reports that fomites have not actually been shown to be an important source of transmission for COVID-19. This includes our uniforms (fabrics generally tend to be poor fomites anyway as they absorb the water from the droplet and desiccate, or dry out, virus particles). While reassuring, this does NOT mean that contact precautions and meticulous uniform containment/cleaning don’t need to be taken.

When EMS arrives Jimmy is extremely distressed and asking what exactly COVID-19 is? Is it a cold? Is it pneumonia? Is it SARS?

History:

- Coronaviruses are human and animal pathogens

- There are 7 known strains of this virus:

- 1 strain caused Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in 2003 (SARS-CoV-1)

- 1 strain causes COVID-19 (the clinical syndrome is called COVID-19, the virus is technically called SARS-CoV-2. It was named this way due to similarities in clinical effects, structure, and mechanism of infection to SARS-CoV-1)

- 1 strain started causing Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in 2012, with low numbers of cases still being reported (MERS-CoV)

- 4 strains only cause minor respiratory symptoms like a cold

SARS CoV-2 (COVID-19)

A great interactive map can be found here with the most current numbers. At the time of this writing, there were almost 1.3 million cases worldwide, with the US being the epicentre.

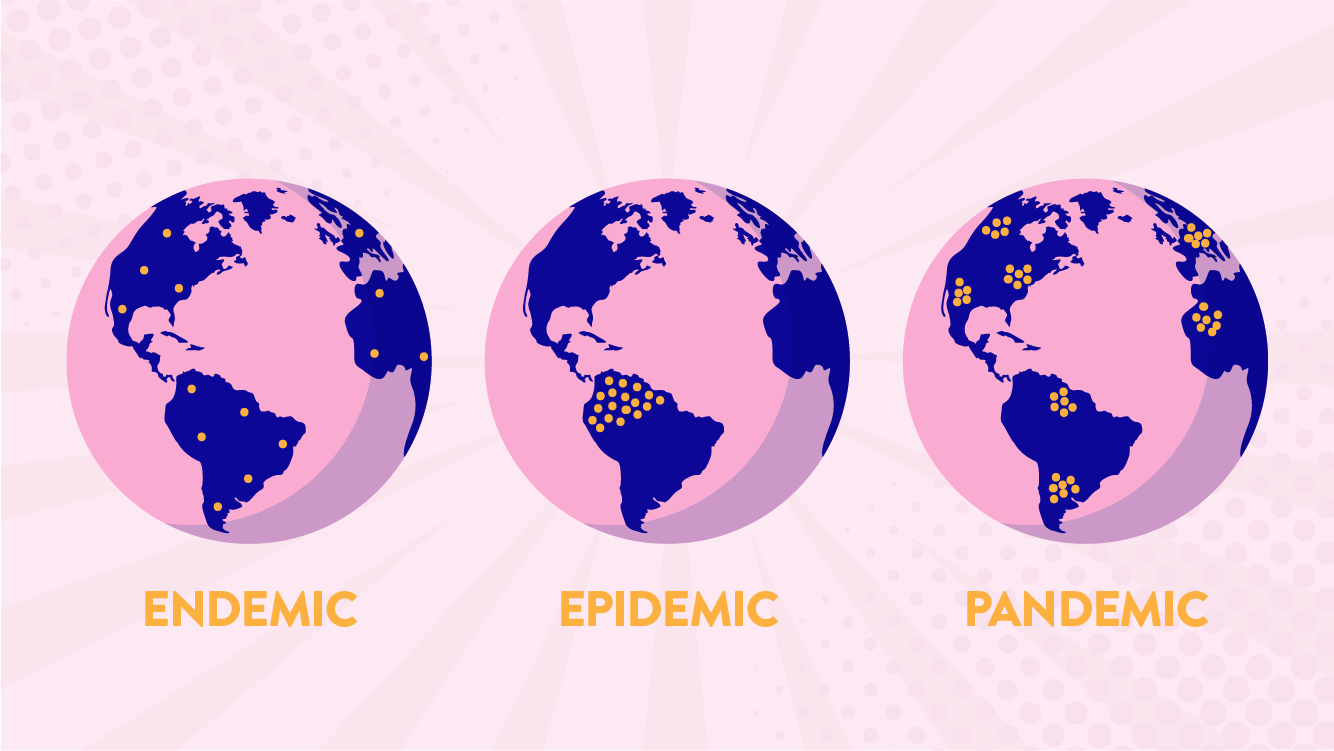

At the end of 2019, novel coronavirus (COVID-19) was identified as the cause of various cases of pneumonia in Wuhan, China. It started off as a local epidemic, and eventually due to globalization and worldwide spread, became a pandemic. There was an initial association with a seafood market that sold live animals in China where most patients either worked or visited (now closed) thus zoonotic transmission could have occurred. Despite its animal origins, however, there is no evidence that companion animals such as dogs or cats can transmit the infection to people.

The incubation period for the vast majority of those infected ranges from 0 to 14d, with the median being 5d.1 The range of infectivity can vary widely and there is a possibility that it is more infectious in the earlier stages of the disease – however this is still being investigated.1 In one study the median duration of viral shedding was 20d, although this ranged from 8 to 37d. We don’t really know what to do with this information though, since viral shedding doesn’t necessarily indicate infectivity. Another way to look at infectivity is to see how long the virus can be cultured (grown). In one study this was only 8d (however, these were mild illnesses, so more severe illnesses may remain contagious for longer).

In terms of how COVID-19 presents, there are no specific symptoms that reliably distinguish COVID-19 from other viral respiratory infections. The clinical syndromes associated with COVID-19 may include:

Cold – this is most patients, especially younger patients without comorbidities. This often includes:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Cough (new or worsening) – usually dry

- Decreased appetite

- Body aches

- Shortness of Breath

Less commonly, patients may report

- Headache

- Sore throat

- Runny nose

- GI symptoms such as nausea and diarrhea have also been reported but less commonly

Anosmia (loss of smell) and dysgeusia (abnormal taste) have also been reported.

Pneumonia – even the usually benign strains of coronavirus can lead to pneumonia in patients with comorbidities.

ARDS/atelectasis – basically, the lungs are filling with fluid and the alveoli collapsing, preventing oxygenation and ventilation.

Cytokine storm – an uncontrolled systemic inflammatory response that leads to multiorgan failure.

Cardiac complications – myocarditis, cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias.

DIC – an imbalance between clotting and bleeding that can be very challenging to manage.

How do we screen potential patients with COVID-19?

Screening recommendations have changed significantly over the last few weeks. While initially PHO provided fairly rigid testing guidelines, the current approach is testing based on clinical assessment. They do offer suggestions for who should be prioritized for testing, however:

- Symptomatic health care workers (regardless of care delivery setting) and staff who work in health care facilities

- Symptomatic residents and staff in Long Term Care facilities and retirement homes and other institutional settings i.e. Homeless shelter (as per outbreak guidance)

- Hospitalized patients admitted with respiratory symptoms (new or exacerbated)

- Symptomatic members of remote, isolated, rural and/or indigenous communities

- Symptomatic travellers identified at a point of entry to Canada

Primary surveillance is aimed at early detection and containment, while the secondary objective is to characterize clinical features and the pattern of spread of of COVID-19.

How is COVID-19 managed?

Supportive care for symptomatic patients

Mild – home management is appropriate for these patients if they can be adequately isolated. Their management focuses on preventing transmission and monitoring for worsening symptoms. These patients should isolate themselves and wear a face-mask if in the same room/vehicle with another person. Frequent disinfection of surfaces is also very important. As discussed above, the duration if infectivity from COVID-19 hasn’t been fully elucidated yet. Thus, the optimal duration of isolation is unknown. PHO is recommending patients with symptoms of COVID-19 to remain isolated for 14d after the symptoms started, while CDC recommends patients can come out of self-isolation when it’s been at least 7d since the onset of symptoms, it’s been 72h without a fever, and other symptoms are improving (or you have two negative tests 24h in a row and are afebrile with improving symptoms

Severe – hospitalization and ICU may be warranted. Not much will change for paramedics, whoever. Administer oxygen if required and following local direction on the safest options. Give IV fluids if hypotensive. Administer pain control if indicated (note that there have been no clinical or population studies that address the highly publicized risk of NSAIDs in COVID-19 risk and WHO does not recommend avoiding NSAIDs when clinically indicated.) These are the same basic tenets of care that will be provided in hospital, with nuanced therapies provided for select patients.

Advanced therapies

At the moment, there are no approved specific therapies for COVID-19 and treatment is aimed at supportive care. However, there are potential therapies on the horizon:

- Remdesivir is an anti-viral medication with weak evidence for MERS-CoV

- Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine are anti-virals and anti-inflammatory medications. These medications seem to directly interfere with the cellular receptor through which SARS-CoV-2 gains access to the body. There is limited animal, laboratory, and human evidence to support its effectiveness and it sounds like better controlled trials are being started. In addition, it may have additional benefits when combined with the antibiotic azithromycin – given relative short-term safety and lack of effective interventions for COVID-19 some clinicians think it is reasonable to use in severe hospitalized patients

- Tocilizumab is a medication that modulates the immune system to inhibit inflammatory reactions.

As his you look after Francesca, Jimmy asks what his wife’s prognosisis ?

This is a question that’s on everyone’s minds. Unfortunately, our limited testing resources make this a very difficult question to answer. Our testing strategy has emphasized the testing of hospitalized patients, who are innately sicker, over those with discharge home with cold symptoms and advice to self-isolate. So, our testing strategy is biased towards identifying the sickest of the sick who are more likely to die. This gives us a skewed calculation, with high numerator (deaths) and a low, but incomplete, denominator (everyone who has COVID). The numbers we have from other countries range from 0.9% to 12% – in addition to testing strategies, this is influenced by the population demographics, availability of health care resources, and potentially changes in the virus itself.1

- 1.McIntosh K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19?search=covid%2019§ionRank=1&usage_type=default&anchor=H1636679944&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=1~150&display_rank=1#H4156151029. Published April 4, 2020. Accessed April 6, 2020.