You have just finished seeing a 12-year-old boy who fell off the monkey bars about an hour ago. He has an obvious deformity to his right elbow and you suspect a displaced fracture that will require reduction. You would like to use procedural sedation to facilitate the reduction, but an empty granola bar wrapper stops you in your tracks. “We missed dinner rushing here and he couldn’t resist,” his mom says. Staring at the granola bar wrapper, you wonder if it is truly necessary to delay the intervention to keep him NPO prior to the procedural sedation.

What is NPO?

Nil per os (NPO), a latin term meaning “nothing by mouth,” is a medical order to withhold fluids and food. Patients in the emergency department (ED) are commonly given a default NPO status when they arrive and prior to being seen by a physician. For multiple reasons, they are often kept NPO as the default even after physician assessment. The issue is complex; eating within an NPO timeframe may mean possible cancellation and subsequent delay of study or intervention, whereas excessive fasting can contribute to patient “hangriness,” dehydration, poor glucose control, and inappropriate withholding of routine medications.1 A retrospective study from the Mayo Clinic found that, due to either the overly long or unnecessary nature of the NPO status, approximately half of missed meals could have been avoided.2

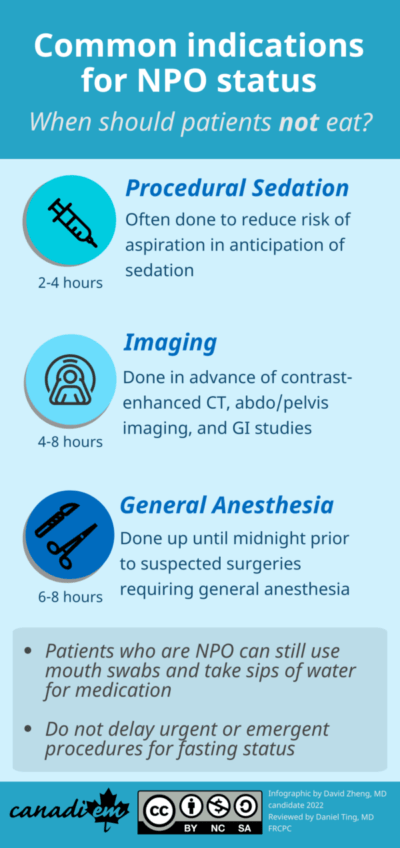

In this article, we will go over conventional indications for NPO orders, the appropriate NPO status durations, and highlight contentious NPO indications to equip you with a framework to better answer a common question from patients: “Can I eat?”

Note: Even patients who are NPO are still permitted to take sips of water for medication and mouth swabs to assuage dry mouth.

NPO Scenarios

Surgery under general anesthesia

Many patients and their family members may express worry about undergoing procedures requiring general anesthesia and have heard of the “nothing by mouth after midnight” rule for daytime procedures. In the ED, patients are often diagnosed with conditions requiring surgeries or procedures in the morning (e.g., endoscopy for a stable GI bleed), and are held overnight in the ED for various reasons, including hospital overcapacity. Due to the changing standards among anesthetic societies worldwide, answering the question of, “Can I eat or drink before my surgery or procedure?” requires more nuance.

General anesthesia reduces esophageal sphincter tone and attenuates reflexes that prevent asphyxiation.3 While rare, this may lead to respiratory sequelae ranging from mild coughing to acute respiratory distress syndrome or even death.4

In the past, many hospitals have enforced the NPO rule by midnight prior to a patient undergoing general anesthesia at any time the following day. However, as procedures may often be delayed, patients may end up waiting for significant periods of time leading to the previously listed adverse effects of fasting. As such, newer recommendations from the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society (CAS) aim to minimize time spent fasting prior to undergoing surgery.5

Caution: For fasting guidelines, it is imperative to distinguish whether a procedure is deemed urgent/emergent versus an elective procedure. For emergent cases, it is probably better to err on the side of caution and keep patients NPO. In the interim, maintenance fluids including dextrose can be given.

Broadly speaking, it is safe for patients to eat up until midnight prior to the procedure. In the case of patients held in the ED, it can be helpful to clarify and specify NPO status with the consulting service. For elective procedures the CAS has recommended the following minimal durations for fasting prior to the procedure:

| Adult | Pediatric |

| Eight hours after a large meal of solids particularly containing protein (e.g., meat) or fatty foods Six hours after a light meal (e.g., non-fatty meal such as toast) Two hours after ingestion of clear fluids for adults | Six hours after ingestion of infant formula, non-human milk, or expressed breast milk fortified with additions Four hours after ingestion of breast milk One hour after ingestion of clear fluids for infants and children |

Ultimately, to reduce unnecessary strain on the patient and their family members, we should be aware of the minimal durations of fasting with respect to the patient’s oral intake. Although seemingly simple, a thorough patient history may help us prevent unnecessary restrictions on a patient’s oral intake and thereby improve their overall quality of stay.

Procedural sedation in the ED

Similar to general anesthesia, fasting is often done prior to a procedural sedation (or even “just in case”). This practice is somewhat supported by published guidelines for fasting, though evidence shows that the risk for adverse events in procedural sedation is very low.6

Dr. Justin Morgenstern’s wrote an excellent review on First10EM, and in brief, he concluded that “procedural sedation is incredibly safe.”7 As thorough as First10EM is, we can add even more to the literature review. In a study of propofol and etomidate for sedation, Miller et al. showed no major adverse events related to PO intake, regardless of fasting status.8 In a pediatric population, Stewart et al. showed both a low rate of adverse events and that fasting status made no difference in the rate of adverse outcomes during procedural sedation.9

Another literature review showed much of the same: procedural sedation carries a very low risk for aspiration. The authors did identify some risk factors, the type of procedure being one (upper endoscopy is the largest culprit), and patient comorbidities being another.10 Overall, the authors concluded that aspiration “appears largely idiosyncratic and unpredictable.” Aspiration isn’t the only risk with sedation; hypoxia, hypotension, and laryngospasm might also be on our minds. However, yet another meta-analysis concluded that the incidence of these events are still “exceedingly rare,” and the reviewers found no deaths in any of the thousands of cases reviewed.11

For further guidance, we can turn to our colleagues in anesthesia. The International Committee for the Advancement of Procedural Sedation has made a guideline for fasting for procedural sedation.6 The authors provide some helpful risk factors to guide decision-making, and the article itself is worth a full read, but a good take-home message from this is don’t delay urgent or emergent procedures for fasting status.

Awaiting Imaging

What if, instead of falling from the monkey bars, our 12 year-old presents after an 8 hour history of severe abdominal pain localized to the right lower quadrant? You are certain that you would like to image his abdomen to rule out appendicitis, but more importantly, can he eat?

Imaging is another frequent reason for NPO status. Similar to procedural sedation, NPO status is often traditionally recommended for imaging requiring intravenous contrast which may cause nausea and subsequent aspiration. Beyond preventing aspiration, NPO status may also be recommended to optimize visualization; for imaging of the abdomen, gastrointestinal tract contents might obscure the intestinal lumen. For ultrasonography, the postprandial contraction of the gallbladder and presence of bile gas and food may make the biliary tree less visible. Other common traditional imaging indications for NPO status are listed in Table 1. However, several studies have questioned whether eating creates an adverse risk during contrast-enhanced CT imaging,12,13 or if eating obscures image quality during ultrasonography.14,15 In addition, NPO policies vary from institution to institution. With this in mind, while ordering an imaging study in the ED, it may be worth asking your local radiologist and asking whether they need the patient to be NPO for the purpose of visualization.

| Requires NPO | Doesn’t require NPO | |

| XR | Routine XR | |

| CT | Contrast-enhanced CT | Non-contrast enhanced CT |

| Ultrasound | Biliary tract (Gallbladder) Aorta Liver (including hepatic doppler) Pancreas Spleen | Carotid (Doppler) Testicles DVT (Doppler) Kidney Pregnancy Soft tissue Pelvis |

| MRI | Abdo/Pelvis MRCP | All other MRIs (e.g., Spine, Brain) |

| Other | GI studies (e.g., Esophagram, upper GI study, Endoscopy, Barium enemas) | Feeding tube checks Nephrostogram Cystogram |

Miscellaneous Indications

| Requires NPO |

| Hyponatremia – Mostly done to prevent iatrogenic exacerbation of the hyponatremia Stroke (Prior to swallowing screen) Esophageal perforation Necrotizing enterocolitis Abdominal compartment syndrome |

| Doesn’t require NPO |

| Pancreatitis – Although NPO was traditionally recommended for pancreatitis, most experts suggest early oral diet (potentially low fat).16 |

Bottom Line

While firm NPO restrictions to prevent aspiration events have long been institutionalized for medical procedures, practice guidelines are gradually easing to be more permissive. It’s also important to consider that keeping patients NPO is itself not without its own risks, with concerns for hypoglycemia, hypovolemia, and falls. In the ED, considerations around NPO status revolve largely around impending surgical procedures, conscious sedations, and imaging studies. While evidence is shifting towards permissiveness in oral intake, keep in mind local protocols and practices. When unsure, it’s usually better to err on the side of caution by keeping patients NPO. Clarify with your attending, consultant, and/or radiologist at the earliest opportunity, and take it upon yourself to reassess fasting status when more information is available.

References

- 1.Wickerham AL, Schultz EJ, Lewine EB. Nil per Os Orders for Imaging. JAMA Intern Med. Published online November 1, 2017:1670. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3943

- 2.Sorita A, Thongprayoon C, Ahmed A, et al. Frequency and Appropriateness of Fasting Orders in the Hospital. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Published online September 2015:1225-1232. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.07.013

- 3.COTTON BR, SMITH G. THE LOWER OESOPHAGEAL SPHINCTER AND ANAESTHESIA. British Journal of Anaesthesia. Published online January 1984:37-46. doi:10.1093/bja/56.1.37

- 4.Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical Significance of Pulmonary Aspiration during the Perioperative Period. Anesthesiology. Published online January 1, 1993:56-62. doi:10.1097/00000542-199301000-00010

- 5.Dobson G, Chow L, Filteau L, et al. Guidelines to the Practice of Anesthesia – Revised Edition 2020. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth. Published online November 27, 2019:64-99. doi:10.1007/s12630-019-01507-4

- 6.Green SM, Leroy PL, Roback MG, et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus statement on fasting before procedural sedation in adults and children. Anaesthesia. Published online December 2, 2019:374-385. doi:10.1111/anae.14892

- 7.Morgenstern J. NPO for sedation? Don’t swallow the myth. First10EM. Published online May 7, 2018. doi:10.51684/firs.5875

- 8.Miller KA, Andolfatto G, Miner JR, Burton JH, Krauss BS. Clinical Practice Guideline for Emergency Department Procedural Sedation With Propofol: 2018 Update. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Published online May 2019:470-480. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.12.012

- 9.Stewart RJ, Strickland CD, Sawyer JR, et al. Hunger Games: Impact of Fasting Guidelines for Orthopedic Procedural Sedation in the Pediatric Emergency Department. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. Published online April 2021:436-443. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.10.038

- 10.Green SM, Mason KP, Krauss BS. Pulmonary aspiration during procedural sedation: a comprehensive systematic review. British Journal of Anaesthesia. Published online March 2017:344-354. doi:10.1093/bja/aex004

- 11.Bellolio MF, Gilani WI, Barrionuevo P, et al. Incidence of Adverse Events in Adults Undergoing Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. Carpenter C, ed. Acad Emerg Med. Published online January 22, 2016:119-134. doi:10.1111/acem.12875

- 12.Neeman Z, abu Ata M, Touma E, et al. Is fasting still necessary prior to contrast-enhanced computed tomography? A randomized clinical study. Eur Radiol. Published online September 8, 2020:1451-1459. doi:10.1007/s00330-020-07255-0

- 13.Tsushima Y, Seki Y, Nakajima T, et al. The effect of abolishing instructions to fast prior to contrast-enhanced CT on the incidence of acute adverse reactions. Insights Imaging. Published online October 23, 2020. doi:10.1186/s13244-020-00918-y

- 14.Ehrenstein BP, Froh S, Schlottmann K, Schölmerich J, Schacherer D. To eat or not to eat? Effect of fasting prior to abdominal sonography examinations on the quality of imaging under routine conditions: A randomized, examiner-blinded trial. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. Published online January 2009:1048-1054. doi:10.1080/00365520903075188

- 15.Zhou W, Chen D, Jiang H, et al. Ultrasound Evaluation of Biliary Atresia Based on Gallbladder Classification: Is 4 Hours of Fasting Necessary? J Ultrasound Med. Published online January 25, 2019:2447-2455. doi:10.1002/jum.14943

- 16.Farkas J. Acute Pancreatitis. The Internet Book of Critical Care (IBCC). Published September 28, 2021. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://emcrit.org/ibcc/pancreatitis/#nutrition

Reviewing with the Staff

\"Can I eat?\" is one of the most common questions I get asked by patients when I am on shift. I do not recall ever being formally taught the indications for keeping patients NPO in the Emergency Department, and I believe many trainees and staff physicians are in the same boat. This article addresses this knowledge gap by outlining a general \"Rule of Three\" for keeping patients NPO: 1) Expected need for surgical management, 2) Expected need for procedural sedation, and 3) Expected need for abdominal imaging studies. By using this general Rule of Three as a starting point, one can start to build up a more nuanced understanding of why (and why not) patients should be kept NPO and give patients who should be allowed to eat an improved experience in the Emergency Department.