This post is part two of a two-part series. You may review the previous post here.

In the last post, we followed Lucas, a 26 year old male who presented to the ED with bizarre behaviour and aggression. When we left off, he was becoming increasingly agitated and paranoid despite your best efforts in de-escalating the situation. He is beginning to yell at staff and refuses to cooperate with any questioning.

Approach to Restraints

Indications and General Principles

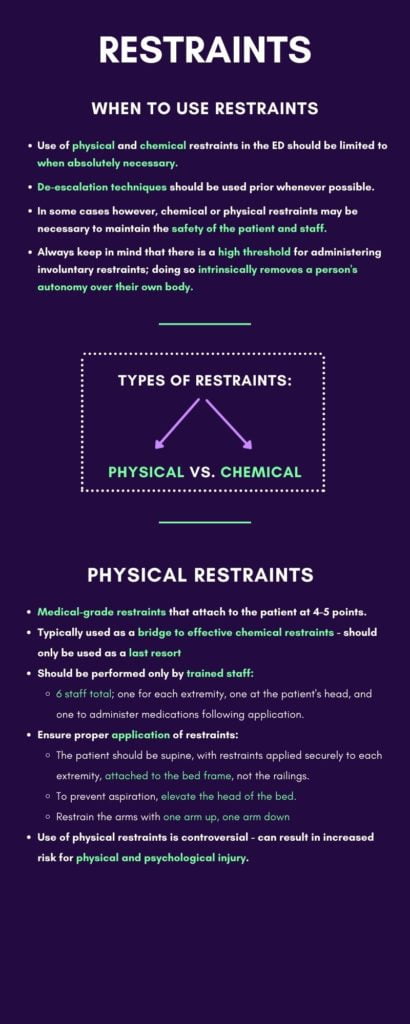

The use of physical and chemical restraints in the Emergency Department should be limited to when absolutely necessary. When possible, de-escalation techniques, behavioural techniques, and shared-decision making in medication administration should be utilized. Of course, there are instances where these techniques are ineffective, or the threat of imminent harm to staff or patient necessitates application of restraints. When these situations occur, it’s important for practitioners to be knowledgeable and comfortable with the interventions used.

There is a high threshold for administering involuntary restraints; after all, doing so intrinsically removes a person’s autonomy over their own body. Restraints may not be applied for reasons such as convenience or retaliation. Under the Patient Restraints Minimization Act of Ontario, patients may only be restrained “if it is necessary to prevent serious bodily harm to him or her or to another person”.1 Restraint use in the ED is much higher than in other inpatient settings2, likely owing to the acute presentations of its patients and the lack of therapeutic support established so early in the visit. However, it’s important to be cognizant of the deleterious effects of restraint use to therapeutic rapport throughout the patient’s admission.

Types of Restraints

Physical Restraints

Physical restraints are medical grade restraints that typically attach to the patient at 4 or 5 points. These should be used only as a last resort, typically as a bridge to effective chemical restraints. The continued use of physical restraints in the Emergency Department is controversial, with studies demonstrating that its use can result in increased risk for physical and psychological injury.3

Application of restraints should only be done by trained staff. There should be at least 6 staff to assist; one for each extremity, one at the patient’s head, and one to administer medications (application of physical restraints should always be followed by chemical sedation).4 It is best to have one team leader giving instructions at this time. The patient should be positioned supine, with restraints applied securely to each extremity and attached to the bed frame rather than the railings . To prevent aspiration, it is best to elevate the head of the bed while the patient remains supine.5

Chemical Restraints

Chemical restraints are medications used to calm severely agitated patients. Commonly used medications include benzodiazepines like lorazepam (Ativan) and midazolam (Versed), first-generation antipsychotics like haloperidol (Haldol), second-generation antipsychotics like olanzapine (Zyprexa) and risperidone, and ketamine. Routes of administration can vary from oral, intravenous, intramuscular, and sublingual.

When selecting a medication, it is important to consider time and ease of administration required. Different clinicians will have their own preferred “cocktail” of medications that they turn to. One might colloquially hear of the “B-52,” or “5 and 2,” typically referring to 5 mg of haloperidol and 2 mg of lorazepam (a combination of a first generation antipsychotic and a benzodiazepine, with the ability to mix both in the same syringe) +/- diphenhydramine, an anticholinergic that may prevent EPS. Remember to always consider the etiology of the presentation in front of you when considering medication choices. UpToDate guidelines suggest the following approach5:

For severely violent patients who require immediate sedation:

- Rapidly acting first generation antipsychotic alone.

- Benzodiazepine alone.

- A combination of a first generation antipsychotic and benzodiazepine.

For patients with agitation from drug intoxication or withdrawal:

- Benzodiazepine alone.

For patients with undifferentiated agitation:

- Preferred: benzodiazepine.

- First generation antipsychotic.

For agitated patients with a known psychotic or psychiatric disorder:

- Preferred: First Generation antipsychotic.

- Second generation antipsychotic.

As alluded to in the de-escalation segment, it is always preferable to involve the patient in decision-making; offering choices like choosing between a dissolving tablet and an injection can help the patient maintain their sense of autonomy.

Following administration, it is important to monitor patients for potential side effects to given medications. With benzodiazepines, be aware of any respiratory depression or abnormal somnolence. With antipsychotics, be aware of acute extrapyramidal effects (EPS) such as acute dystonias characterized by sudden, sustained contractions of the mouth, tongue, and eye muscles which should be addressed promptly. First generation antipsychotics may also prolong the QT interval, and thus should be used with caution in patients taking other medications also prolonging QT interval or with congenital disorders prolonging the QT interval, and in patients with likely electrolyte disorders such as hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia.5

Special considerations:

- Alcoholic intoxication: beware of the synergistic effects of alcohol intoxication and benzodiazepines on respiratory depression. These patients may benefit from continuous monitoring or alternative medications.

- Geriatric: benzodiazepine use in the elderly population leads to increased risk of delirium, significantly increasing morbidity and mortality. In these patients, use antipsychotics like haloperidol; start low and go slow.

- Pediatrics: pediatric patients often respond better than adult patients to verbal de-escalation. Should restraints be necessary, home medications (if applicable) should be trialled first, and if ineffective, a second dose administered rather than mixing medications.6 Antihistamines and benzodiazepines may also have a paradoxical effect on young children or children with autism, where agitation is worsened.

When offered the choice between an oral medication or an intra-muscular injection, Lucas expresses that he would prefer the oral route. You administer oral lorazepam, after which his agitation ebbs. After building some rapport, he is now amenable to some medical investigations.

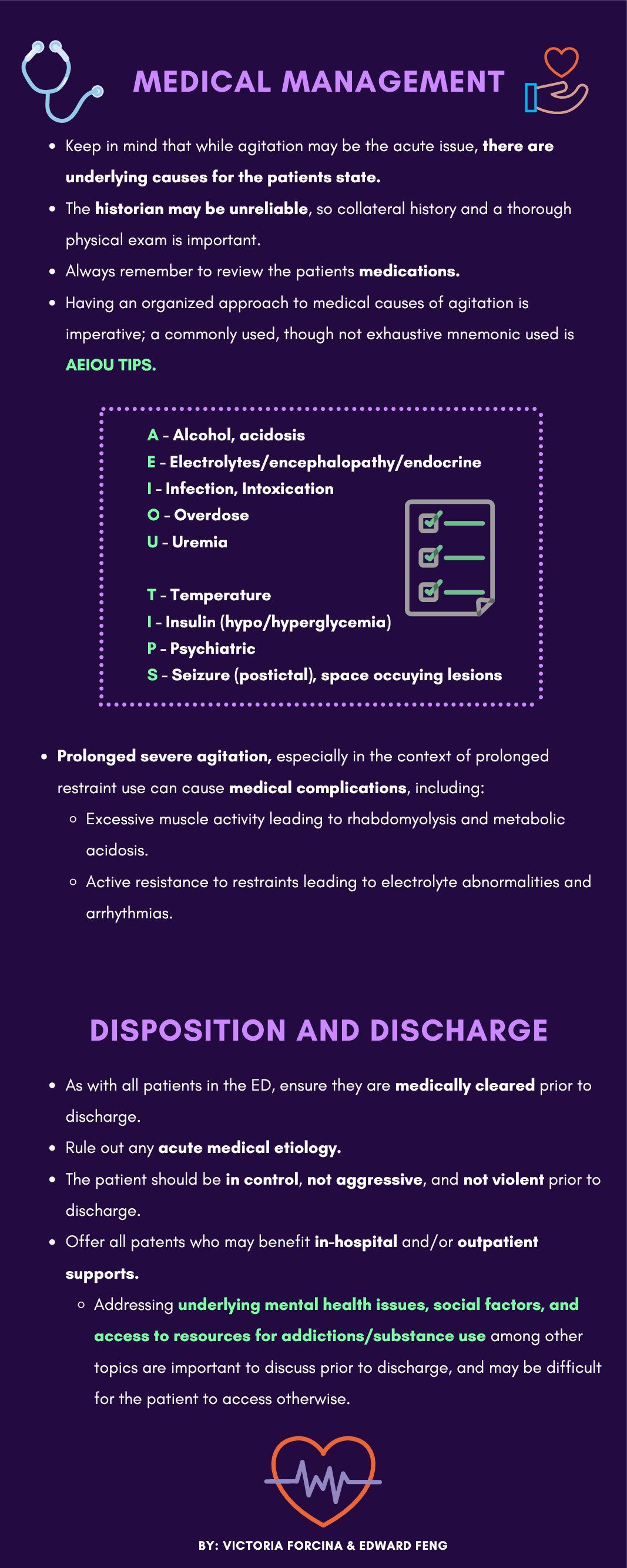

Brief Overview of Medical Management

When assessing acutely agitated patients, have a broad differential in mind and assess for organic (medical) aetiologies for the patient’s presentation. Collateral history and a thorough physical exam is incredibly important, especially in the absence of a willing historian. While severe agitation may be the acute issue that needs intervention immediately, it’s important to keep in mind that there are underlying causes for the patient’s state. The assessment and treatment of the patient continues well after the acute agitation is resolved.

Having an organized approach to medical causes is invaluable in creating an effective plan for investigations and treatment. Make sure to consider primary diagnoses, such as thyrotoxicosis, encephalitis, and sepsis. As the differential diagnosis for agitated patients is nearly identical to altered LOC, below we review a common mnemonic (AEIOU TIPS) for the latter that can be applied to agitated patients.

- Alcohol, acidosis

- Electrolytes/encephalopathy/endocrine

- Infection, intoxication

- Overdose

- Uremia

- Temperature

- Insulin (hypo/hyperglycemia)

- Psychiatric

- Seizure (postictal), space occupying lesions

Make sure to review the patient’s history and medications, and obtain a full set of vitals if possible. Different aetiologies may dramatically alter your interventions. For example, antipsychotic medications would be contraindicated in patients who present with features concerning for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. If a patient was presenting with agitation secondary to alcohol agitation, benzodiazepines should be used with caution given the combined risks of respiratory depression.

Medical complications of severe agitation

Prolonged severe agitation, particularly in the context of prolonged restraint use, can cause medical complications. Excessive muscle activity caused by extended agitation can lead to rhabdomyolysis and metabolic acidosis. Active resistance against restraints may also lead to electrolyte abnormalities and arrhythmias. Of course, do not neglect potential traumatic injuries sustained as a result of agitation or the application of restraints.

Over the next 3 hours, Lucas becomes much more calm and his vitals normalize. He is currently awaiting a psychiatric consultation.

Disposition and Discharge

As with all patients in the ED, the agitated patient must be medically cleared prior to discharge home. The emergency physician should ensure that proper medical investigations have been done to rule out an acute medical etiology accounting for the patient’s presentation. The patient should also be in control, not aggressive, and not violent prior to discharge. It is important to offer all patients struggling with substance use both in-hospital and outpatient supports – addressing underlying mental health issues, social factors, and accessing resources for addictions among other topics are important to discuss and may be difficult for the patient to access otherwise.

You can download the infographics for this article here:

Further Reading on CanadiEM:

- https://canadiem.org/violence-and-agitation-in-the-emergency-department/

- https://canadiem.org/the-agitated-patient-in-the-ed-part-1/

- https://canadiem.org/the-agitated-patient-in-the-ed-part-2/

This post was copy-edited by Casey Jones (@CaseyMAJones).

References

- 1.Government of Ontario . Patient Restraints Minimization Act. Government of Ontario. Published 2017. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/01p16

- 2.Zun L. A prospective study of the complication rate of use of patient restraint in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2003;24(2):119-124. doi:10.1016/s0736-4679(02)00738-2

- 3.Knox D, Holloman G. Use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint: consensus statement of the american association for emergency psychiatry project Beta seclusion and restraint workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):35-40. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6867

- 4.Helman A. Emergency management of the Agitated Patient. Emergency Medicine Cases. Published 2018. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/emergency-management-agitated-patient/

- 5.Moore G, Pfaff J. Assessment and emergency management of the acutely agitated or violent adult. UpToDate. Published 2020. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/assessment-and-emergency-management-of-the-acutely-a gitated-or-violent-adult

- 6.Gerson R, Malas N, Feuer V, Silver G, Prasad R, Mroczkowski M. Best Practices for Evaluation and Treatment of Agitated Children and Adolescents (BETA) in the Emergency Department: Consensus Statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(2):409-418. doi:10.5811/westjem.2019.1.41344

Reviewing with the Staff

The agitated patient spans a range of bio-psycho-social challenges to themselves, physicians, nurses and allied healthcare staff.

Often stigmatized, their presentation can mask severe underlying pathology requiring timely intervention. While protecting the ED team is paramount, the main focus should remain with the patient. A calm, measured approach to de-escalation, restraints and sedation is necessary. A compassionate, open-minded approach to their subsequent management and disposition will ensure the best outcome for all involved.