Introduction

In your first Emergency Department (ED) rotation, you are keen to practice your suturing technique. During a slow shift, you decide to take a look at the suture cart in minor treatment, and realize you can only recognize two of the types available. What is the difference between these sutures and how can you apply them to different presentations? What is the right suture choice?

Often, suture choice is not explicitly taught in medical school and is learned informally. This post aims to explain differences between basic suture types as well as how key patient and wound factors may influence choice. We use a few cases to illustrate, and have searched the literature for the best-available evidence.

The Clinical Question

In patients presenting with lacerations to the ED, how should physical characteristics of the suture type influence choice for primary closure?

[bg_faq_start]Objectives

- To review common suture types used in the ED.

- To describe applications of suture types and techniques based on anatomical location and depth.

Overview

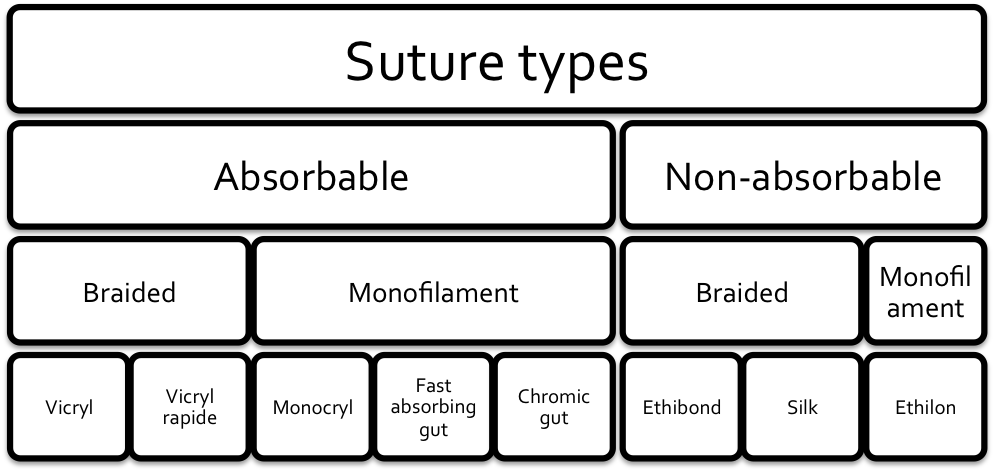

Conceptually, suture types can be divided into four categories: absorbable braided, absorbable monofilament, nonabsorbable braided and nonabsorbable monofilament.

Suture types available in the Kelowna General Hospital ED, divided by type. N.B., “Ethilon” is a nylon nonabsorbable suture. Prolene is a polypropylene nonabsorbable suture that is used in other EDs for similar applications as Ethilon/nylon

| Type of Suture | Time to 50% breaking strength retention | Time to complete absorption |

|---|---|---|

| Vicryl Rapide | 5 days | 42 days |

| Fast Absorbing Gut | 7 days | 21-42 days |

| Monocryl | 1 week | 91-119 days |

| Vicryl | 3 weeks | 56-70 days |

| Chromic Gut | 3-4 weeks | 90 days |

Absorbable sutures do not need to be removed, but are theoretically more inflammatory and may be more likely to be infected. Braided sutures are stronger and their knots are less likely to slip—thus requiring fewer throws and can be cut with short ends—but are more liable to become infected. For the absorbable types, long-lasting sutures provide durable tensile strength but again, have higher infection rates.

We can use this knowledge in the following cases!

The Cases

A series of cases designed to dive into choosing the right suture material!

Case 1- the uncomplicated adult laceration

An otherwise healthy 34-year-old female presents to the ED after cutting the anterior surface of her left leg in a kitchen accident. Following examination you are confident there is no tendon, nerve, or vascular involvement in this clean, 6 cm laceration. What is the best suture type to use?

[bg_faq_start]Answer

There are many factors that go into selecting a suture type. These include tensile strength required for wound closure, site anatomic location of the wound closure, and ability to return for follow up. It is generally accepted that if one uses sutures to repair an uncomplicated laceration, the best choice is a monofilament non-absorbable suture. Monofilament synthetic sutures have the lowest rate of infection [2]. Size 6-0 is appropriate for the face. 3-0, 4-0 or 5-0 may be appropriate for other areas including torso, arms, legs, hands and feet[1] [4]. In general, the smallest diameter that can effectively support the tension on the wound is preferable.

Bottom line: General consensus has been that, when using sutures to repair an uncomplicated laceration in an adult patient, a monofilament non-absorbable suture is preferable (e.g., Ethilon). Most current wound care practices are empirical or based on animal models. To date there are few well-designed clinical trials [5]. However, recent literature has shown similar cosmetic results when comparing absorbable versus non-absorbable suture repair in pediatric patients [6]. This may be generalizable to adult populations, although further research is needed (see case 3). [bg_faq_end]

Case 2- the macerated laceration

A 41 year-old male presents to the ED after he caught his hand on an exposed nail causing a 3 cm laceration with macerated edges that are not well approximated. How important is debridement?

[bg_faq_start]Answer

In a 2001 cross-sectional study by Hollander et al. involving over 5,000 patients with traumatic lacerations, there was a 3.5% wound infection rate [5]. Macerated wound edges were associated with increased rate of infection [7]. The authors postulated that debriding contaminated, macerated tissue to provide smoother wound edges may reduce risk of infection. A literature search revealed little evidence outside of surgical and military literature regarding traumatic lacerations. It is generally accepted, however, that removing devitalized tissue aids in wound healing [8]. If the macerated edges are viable, it is important to carefully bring the edges together with sutures to allow superior cosmesis [2].

Bottom Line: Lacerations with macerated edges are associated with higher risk of infection. Debridement of devitalized tissue to provide smooth wound edges is preferable for wound healing.

[bg_faq_end]

Case 3- the uncomplicated pediatric laceration

A 6-year-old girl presents with a 3 cm clean-appearing laceration over the left cheek after falling against a metal table. Is the use of an absorbable suture acceptable?

[bg_faq_start]

Answer

In cosmetically sensitive areas, sutures are often preferable to skin glue, because they provide more precise apposition of tissue, especially in the pediatric population, whose high skin elasticity predisposes to scar widening over time [9]. The traditional teaching has held that the use of non-absorbable sutures provide a better cosmetic result because they are less inflammatory and reduce the risk of “railroad track” scarring in the skin. However, in the pediatric population, suture placement and removal can be traumatic. Therefore, the use of absorbable sutures may be preferable since they do not need to be removed. A trio of studies performed in Pediatric EDs showed absorbable catgut sutures provided similar cosmesis to nonabsorbable nylon after several months, with no differences in parental satisfaction or wound complications [10-12].

In the adult population, absorbable sutures have long been accepted in the surgical fields, where numerous studies have shown no cosmetic difference between absorbable and nonabsorbable, although whether these results apply to the ED is debatable. Recently, a small ED study examined cosmetic outcomes for extremity repair in adults and found similar cosmesis between Vicryl Rapide and Prolene, although the Vicryl Rapide group had an 11% risk of infection [6]. Another prospective study found no cosmetic difference for facial wounds repaired by fast-absorbing gut, nylon or tissue adhesive, although the study lost almost half its cohort in follow-up [13]. Further study is likely required.

Bottom line: When sutures are indicated for a clean wound on a child’s face, fast-absorbing catgut sutures allow similar cosmesis to non-absorbable sutures. Thus, they are an acceptable alternative, especially if the provider perceives the child may have significant anxiety with suture removal.

[bg_faq_end]

Case 4- the deep laceration

A 52-year-old farmer presents to the Emergency Department after a mishap with a saw. He has a clean-appearing 6 cm laceration. After local anesthesia and irrigation, you notice that the laceration extends deep to adipose tissue. Is there a role for deep sutures?

A 52-year-old farmer presents to the Emergency Department after a mishap with a saw. He has a clean-appearing 6 cm laceration. After local anesthesia and irrigation, you notice that the laceration extends deep to adipose tissue. Is there a role for deep sutures?

Answer

When wounds extend to the deep dermis, they are often subject to higher tension. Closing a deep wound under tension increases the risk of scarring as well as complications, such as dehiscence [2,14]

A technique of using absorbable sutures in the dermis and subcutaneous layers can allow the relief of tension and approximate wound edges. Deep sutures can be done in an interrupted fashion. On the initial throw, the needle should be inserted in the deep dermal layer and exit in the superficial dermal layer (deep-to-superficial). On the second throw in the opposite margin of the wound, the needle first enters the dermis and exits the deep dermal layer (superficial-to-deep). This allows the knot to be buried deep in the wound, which prevents the knot from forming an uncomfortable bump and from interfering with dermal healing [2,14].

Keep in mind the following:

- The number of deep sutures should be kept to a minimum since each suture is a foreign body and a possible nidus of infection [2]. A wound under suspicion of contamination should be closed without deep stitches.

- Avoid suturing adipose tissue as it does not provide good purchase (grip) and only increases the risk of infection [2,14]

- In facial lacerations, an ED study found that using deep sutures in simple wounds smaller than 3 cm did not result in a cosmetically superior outcome than simply closing the skin with nonabsorbable suture [15].

Once deep sutures have been placed, the epidermis can be closed in the usual fashion.

Bottom line: When sutures are indicated in a deep laceration, the judicious use of interrupted, absorbable sutures (e.g., Vicryl) can relieve skin tension, ease closure and improve ultimate cosmetic outcome. Vicryl is often a good choice here because it provides long-term tensile strength and has a mid-range absorption time, which reduces foreign body infection risk (Table 1). [bg_faq_end]

Reviewing with Staff (Brian Lin)

Reviewer: Brian Lin, MD, FACEP. Dr. Lin is an attending physician at Kaiser Permanente, San Francisco, and a Clinical Assistant Professor at UCSF. He is the author of the awesome emergency medicine wound care website, www.lacerationrepair.com.

Bottom Line

The authors give an excellent summary of the ‘boring’ but essential topic of suture selection and basic closure techniques for many common wounds seen during an ED shift. While peering in to a suture cart and envisioning how to perform a closure can be intimidating for the new learner, the process is much simpler if some basic tenets are kept in mind:

- The best suture for a given laceration is the smallest diameter suture, which will adequately counteract static and dynamic tension forces on the skin.

- The stronger an absorbable suture is, the greater its absorption time, and the greater its risk of causing a foreign body reaction within a wound. This principle is especially important when considering the use of buried sutures (such as interrupted deep dermal sutures) or planned non-removal of epidermal sutures (as discussed in Case 3).

The authors briefly discuss the techniques of simple interrupted suturing, both for superficial skin closure and for deep dermal placement. These are essential techniques for the new learner to master, as almost any traumatic laceration can be repaired with knowledge of these techniques alone. As skills develop, additional techniques for more efficient and elegant closure can be added to the practitioner’s armamentarium.

References

- Retrieved from http://www.ethicon.com/healthcare-professionals November 14, 2014.

- Simon, B.C., Hern, H.G. (2014). Wound management principles. In: Marx, J.A., Hockberger R.S., Walls R.M., et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th Ed, Vol 1. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia. 2014, 756-763.

- Retrieved from http://www.pharmacopeia.cn/v29240/usp29nf24s0_m80200.html November 19, 2014.

- Thomsen, T. W., Barclay, D. A., & Setnik, G. S. (2006). Basic Laceration Repair. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(17), e18.

- Hollander J., & Singer, A. (1999). Laceration Management. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 34(3), 356-367.

- Tejani, C., Sivitz, A.B., Rosen, M.D, Nakanishi, A.K., Flood, R.G., Clott, M.A., …& Luck, R.P. (2014). A comparison of cosmetic outcomes of lacerations on the extremities and trunk using absorbable versus nonabsorbable sutures. Academic Emergency Medicine, 21(6), 637-643.

- Retrieved, from http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/tools/guidelines_prevention_and_management_wound_infection.pdf October 16, 2014.

- Retrieved from http://www.med.uottawa.ca/procedures/wc/e_treatment.htm#c3 October 16, 2014.

- Parell, G.J., Becker, G.D. (2003). Comparison of absorbable with nonabsorbable sutures in closure of facial skin wounds. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery, 5(6), 488-490.

- Karounis H., Gouin S., Eisman H., Chalut, D., Pelletier, H., & Williams, B. (2004). A randomized, controlled trial comparing long-term cosmetic outcomes of traumatic pediatric lacerations repaired with absorbable plain gut versus nonabsorbable nylon sutures. Academic Emergency Medicine, 11(7), 730-735.

- Luck, R.P., Tredway, T., Gerard, J., Eyal, D., Krug, L., & Flood, R. (2013). Comparison of cosmetic outcomes of absorbable versus nonabsorbable sutures in pediatric facial lacerations. Pediatric Emergency Care, 29(6), 691-695.

- Luck, R.P., Flood, R., Eyal, D., Saludades, J., Hayes, C., & Gaughan, J. (2008). Cosmetic outcomes of absorbable versus nonabsorbable sutures in pediatric facial lacerations. Pediatric Emergency Care, 24(3), 137-142.

- Holger, J.S., Wandersee, S.C., & Hale, D.B. (2004). Cosmetic outcomes of facial lacerations repaired with tissue-adhesive, absorbable, and nonabsorbable sutures. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 22(4), 254-257.

- Singer A.J., & Hollander, J.E. Methods for Wound Closure. In: Tintinalli, J., Stapczynski, J., Ma, O., et al. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A comprehensive study guide. 7th Ed. McGraw-Hill Medical, New York. 2011, 306-310.

- Singer A.J., Gulla J., Hein, M., Marchini, S., Chale, S., & Arora, B.P. (2005). Single-layer versus double-layer closure of facial lacerations: a randomized controlled trial. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 116(2), 363-368.

- “Michele’s Wound”. By Aaron. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.com/nqhqalb January 15, 2015.

- “A Wound”. By Max Sparber. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.com/nl26mfd January 15, 2015.

- “Such Fragile Beings”. By mi.a. Retrieved from http://tinyurl.com/jwxulhf January 15, 2015.

About the Authors:

This article was co-written by Dr. Daniel Ting (@tingdan) and Dr. Jared Baylis (@baylis_jared). The are both residents at the University of British Columbia.

Daniel is UBC Royal College Emergency Medicine resident at Kelowna General Hospital. He tweets about medicine and FOAM @tingdan.

Jared is also a UBC Royal College Emergency Medicine resident based in Kelowna, BC. He is a new contributor to #FOAMed and also a father of two busy boys.