It was an early morning shift at Janus General when I picked up the chart of a 36-year-old female with a two-week history of sore throat.

I walked into the room and see a healthy looking 36 year old woman. Her vitals were stable, but she was febrile. She was reclining on a stretcher, breathing normally and did not appear to be in respiratory distress. She presented with a two-week history of sore throat with intermittent fever, no cough, no dyspnea, and her voice sounds were a bit high pitched but not exactly muffled.

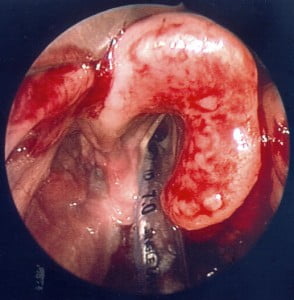

Looking at her, sitting on the bed, I was thinking viral URI or perhaps strep throat. I certainly was NOT thinking “epiglottitis,” a diagnosis I associate with stuff like this:

As I considered her differential she told me that she came into ED because she has been feeling increasingly uncomfortable for the past 2 days. She was taking naproxen for pain but has found that her “throat spasms” when she drinks water which has made swallowing pills hard. That gave me pause as I started my exam.

The left side of her neck was very tender and mildly edematous. She could only open her mouth a bit because her “throat spasms” every time she tries. I grabbed for a tongue depressor to get a better look and almost sent her into a chocking fit! That left me with no better of a look and an even more distressed patient.

The super-star staff physician working the ED that day noted that the presentation was not typical but that “We should scope to make sure he does not have epiglottitis.” ENT was consulted and she was quickly whisked away for flexible laryngoscopy. Twenty minutes later, I got a page from a very excited ENT physician, “You were so right! It’s epiglottitis!”

The lesson I took from this is that while children are not little adults, adults are not big children either. The presentations of “pediatric” diseases can be subtler and less typical the rare times they present in adults.

Quick and Dirty Facts About Adult Epiglottitis

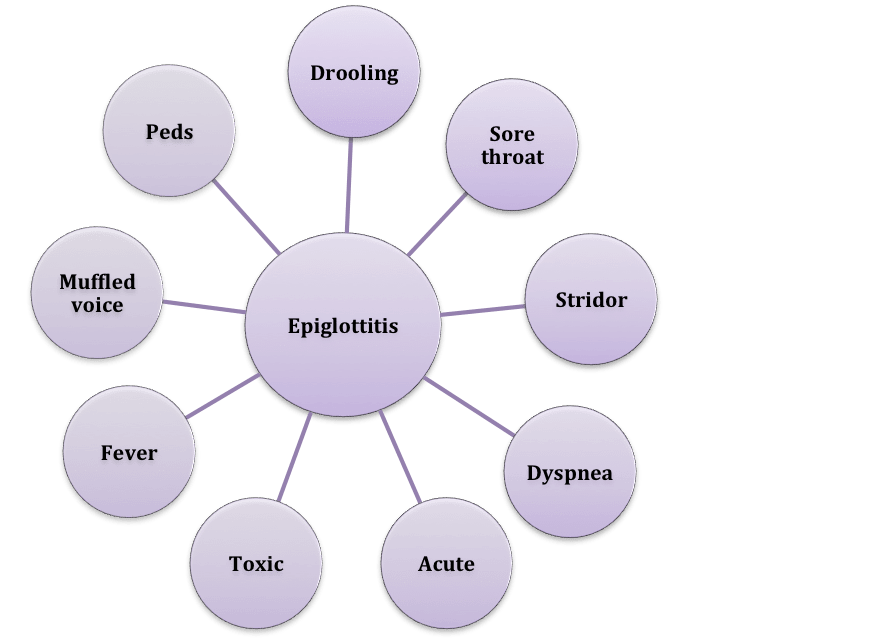

The incidence of epiglottitis is 1-4 per 100 000 (Solomon 1998) with a mortality of 7-20% (Carey 1996). Common causes can include bacteria (H. Flu type B), viruses (herpes simplex), fungi (candida albicans), and non-infectious irritation (trauma, chemicals, heat, inhalation of heated objects (smoking illicit drugs). Common clinical features include sore throat and painful dysphagia. Less frequent causes that may be predictrors of airway loss (this is controversial) include drooling and stridor.

Differential Diagnosis

- Deep space abscesses

- Lingual tonsillitis

- Laryngeal tumors

- Toxic/caustic inhalation, aspiration, or ingestion

- Acute angiodema

- Aortic dissection

Radiographic evidence

The thumb-print sign is the classical radiographic finding in epiglottitis and is named because the epiglottis seems to swell to the size/shape of a thumb print!

Laryngoscopy evidence

This picture shows an incredibly swollen epiglottis. Note that direct laryngoscopy is not advised because it may provoke airway spasm. This photo was taken with a fiberoptic laryngoscope.

Treatment

Patients are typically admitted to a monitored bed for close airway monitoring and intravenous antibioitics. Antibiotics should be started immediately and cover haemophilus influenza, staph aureus, streptococcus, and pneumococus. The drugs of choice are generally amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or a third generation cephalosporin (Ward 2002). NSAIDS can be used for symptomatic relief and corticosteroids are often recommended although the evidence is controversial. Two separate studies, Dort (1994) and Mayo-Smith (1995), have shown that their use does not reduce the need for and the duration of intubation, or the duration of ICU stay.

The role of airway intervention in adults is controversial and a more conservative approach is recommended (antibiotics, corticosteroids, and humidified oxygen). Some studies suggest basing the decision on patient’s clinical signs and symptom. Factors to consider include respiratory distress, stridor, sitting erect, inability to swallow secretions, and deterioration within 8-12 hours. Other studies propose management based on laryngoscopy findings. Intubate if signs of severe constriction of the supraglottic space and/or vocal cords not visible and/or endotracheal intubation not possible (Wick 2002).

For intubating a patient with epiglottitis, check out Dr. Rich Levitan’s great article from 2011 which offers the following tips:

- Rescue ventilation (LMA, King LT, mask ventilation) may not work in a patient with laryngeal pathology

- Supraglottic airways (LMA, King LT) may obstruct the airway further by pushing the swollen epiglottis over the laryngeal inlet

- If orotracheal or nasotracheal intubation fails, a rapid surgical airway might be required

- Mark the neck in an event that surgical airway becomes necessary

- Flexible fiberoptics are ideal for intubating a patient with laryngeal pathology

- Pharmacological adjuncts (small doses of benzodiazepines and ketamine) should be used to aid in intubation

- Topical medication can be used to help relax the surrounding structures (lidocaine 20cc of 2% can be nebulized)

- Maximize oxygenation efforts throughout the intubation by applying nasal oxygen

- After intubation, take care in preventing unintended extubation through the use of sedatives and muscle relaxants

- Equipment for a surgical airway should be kept at bedside, even after intubation, in case of unexpected extubation

Conclusion

Childhood incidence of epiglottitis has decreased significantly since the routine use of HiB vaccine. Despite an increase in adult cases, it still remains a rare presentation seen in the ED.Adult presentations tend to be subtler than that of children with sore throat, dysphagia, and odynophagia being the more common symptoms (Durell 2011). Often, adult patients not present with signs of airway obstruction, leading to an overall delay in diagnosis (Ng 2008). Prognosis is good, but it’s important to keep it on your differential diagnosis for an adult with a history of sore throat.

This post was edited and peer-reviewed by Teresa Chan (@TChanMD) and Brent Thoma (@Brent_Thoma).

—–

Addendum – Added September 2, 2014

We are proud to announce that this piece by Dr. Viaznikova has been awarded an endorsement by the ALiEM.com website as a certified “Approved Instructional Resource” (AIR). Click here to find out more about the AIR series. Congrats to Tanya on her great work!

![fig temp 5col 2 across [Converted]](http://canadiem.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Thumb-Print-Sign-1-300x272.jpg)