“Spinal cord syndromes? I love those, and never forget them!” – Said nobody, ever. Despite the fact that spinal cord syndromes can be difficult to remember, they are important to recognize and can yield a significant amount of clinical information. We seek to break spinal cord syndromes into an easy to digest and understand discussion.

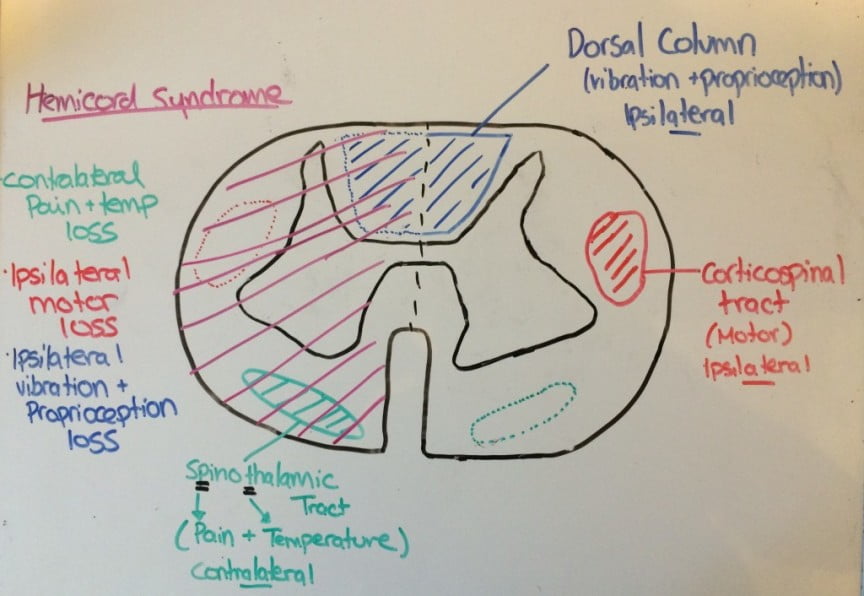

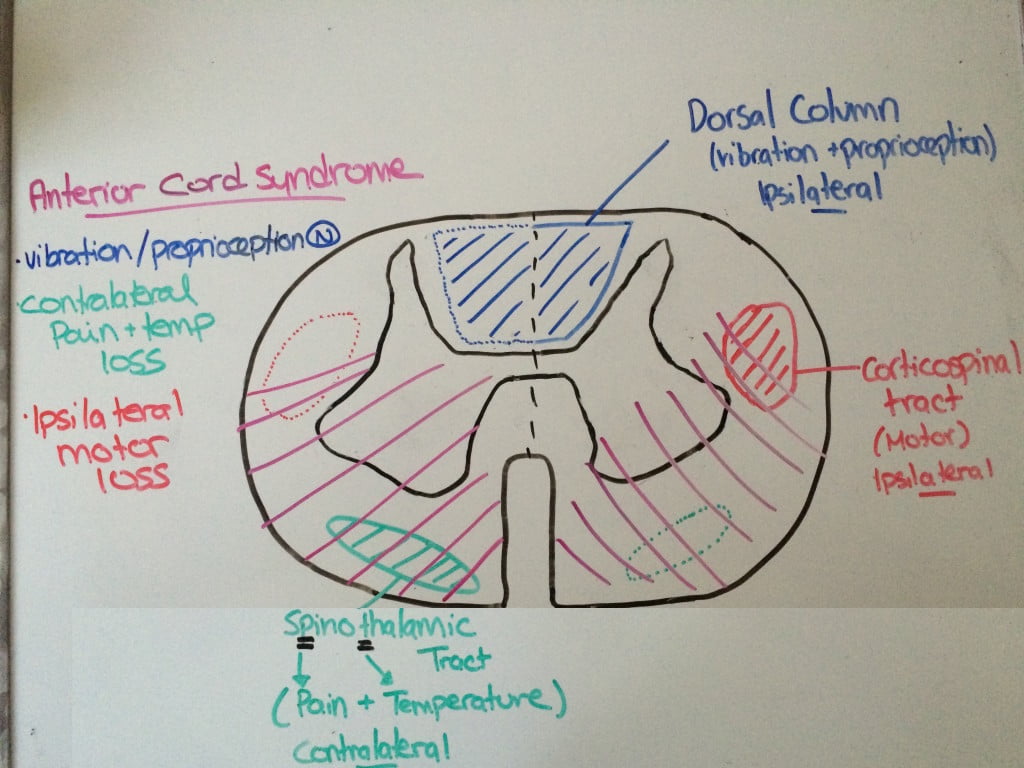

The basis of this discussion is highlighted by the importance of remembering the anatomy, and once you recall this simple diagram, the syndromes become significantly easier to recall:

The spinothalamic tract is intentionally drawn on the opposite side of the cord, to represent that those nerve fibres crossover in the cord, providing contralateral pain and temperature sensation.

On the opposite side of the cord, the dorsal column carries ipsilateral proprioception/vibration, while the corticospinal tract contains ipsilateral motor function.

Spinal Cord Syndromes: Anterior Cord Syndrome

Anterior cord syndrome often occurs as a result of flexion injury, or due to injury to the anterior spinal artery. This may occur as a result of vascular or atherosclerotic disease in the elderly, or iatrogenic secondary to cross clamping of the aorta. These patients have preserved function of their posterior column, and so their proprioception and vibration sense is intact. However, the anterior portion of their cord is affected, and therefore they tend to have bilateral loss of motor function, light touch, pain and temperature below the level of the lesion.

Spinal Cord Syndromes: Central Cord Syndrome

Remember MUD-E!

Motor > Sensory

Upper extremity > Lower extremity

Distal > Proximal

Extension injury

The classic mechanism is the elderly patient who falls, and hits their chin – causing an extension injury of the neck. Distal upper extremity motor function is most medial in the spinal cord, these are the areas that are typically most effected with patchy sensory loss.

Central cord syndrome can often be missed in the ED, as the imaging in these patients is often unremarkable, and their sensory deficits can be patchy. Because it is a clinical diagnosis, it is important for the emergency physician to consider this entity during their assessment, particularly in trauma patients, where this may be overlooked.

Spinal Cord Syndromes: Brown-Sequard Syndrome

Brown-Sequard is a hemi-cord injury, typically noted in the setting of penetrating trauma.

The patient will have injury to their dorsal column, corticospinal tract and spinothalamic tract – therefore causing ipsilateral loss of motor function, and proprioception/vibration. Since the spinothalamic tract crosses over, they will have contralateral loss of pain and temperature.

Spinal shock vs Neurogenic shock

These two terms are often erroneously used interchangeably, however, they apply to two distinct concepts.

Spinal shock is not a true ‘physiologic shock’, and should be thought of more as a ‘spinal concussion’. It is manifested by a flaccid areflexia post spinal cord injury. As edema around the cord resolves, symptoms will improve over a period of days to months, noted by return of the bulbocavernosus reflex (anal sphincter contraction in response to tugging on a foley catheter).

Neurogenic shock is a true distributive shock, in which the patient becomes hypotensive and bradycardic, usually noted with lesions above T6. It is typically a manifestation of decreased vascular resistance and increased vagal tone secondary to autonomic disruption.

Management is focused around optimizing perfusion to the spinal cord, thereby preventing secondary cord injury and ischemia. No great evidence here, but expert opinion suggests targeting a MAP of 85-90.

Bradycardia may be treated with atropine or pacing, while hemodynamic therapy is supportive with fluids and vasopressors to help increase perfusion. There is a potential risk of reflex bradycardia with the use of phenylepiprhine, but this is considered theoretical, and a recent CAEP position statement suggests any vasopressor should be used just to optimize perfusion to the cord. If available, norepinephrine is probably your best option.

Steroids in spinal cord injury remains controversial, with conflicting evidence. The Congress of Neurological Surgeons has suggested that steroid therapy “should only be undertaken with the knowledge that the evidence suggesting harmful side effects is more consistent than any suggestion of clinical benefit”. The Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians is now recommending against the use of high dose steroids as standard of care. Therefore, the administration of steroids should be undertaken in consultation with local neurosurgeons/established protocols.

[bg_faq_start]References

- Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Hellenbrand KG, et al. Methylprednisolone and neurological function 1 year after spinal cord injury. Results of the National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. J Neurosurg. 1985 Nov. 63(5):704-13.

- Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, et al. Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the Third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Randomized Controlled Trial. National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. JAMA. 1997 May 28. 277(20):1597-604.

- Bracken MB. Steroids for acute spinal cord injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002. CD001046.

- Djogvic D, MacDonald S, Wensel A, Green R, Loubani O, Archambault P, Bordeleau S, Messenger D, Szulewski A, Davidow J, Kircher J, Gray S, Smith K, Lee J, Benoit JM, Howes D. Vasopressor and Inotrope use in Canadian Emergency Departments: Evidence Based Consensus Guidelines. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2015; 17(S1)1-16.

- Hadley MN, Walters BC, Grabb PA, et al. Pharmacological therapy after acute spinal cord injury.Neurosurgery. 2002. 50 Suppl:63-72.

- Hurlbert RJ, Hamilton MG. Methylprednisolone for acute spinal cord injury: 5-year practice reversal. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008 Mar. 35(1):41-5.

- Jia X, Kowalski RG, Scuibba DM, Geocadin RG. J Intensive Care Med. 2013 Jan;28(1)12-23.

- Levi L, Wolf A, Belzberg H. Neurosurgery. 1993; 33(6)1007.

- Nesathurai S. Steroids and spinal cord injury: revisiting the NASCIS 2 and NASCIS 3 trials. J Trauma. 1998 Dec. 45(6):1088-93.

- Vale FL, Burns J, Jackson AB, Hadley MN. J Neurosurg. 1997;87(2)239