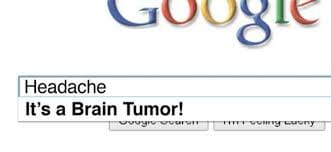

“Well, I looked up my symptoms on Google, and it said I was having a heart attack”, we’ve all had this patient interaction before. We live in an era where information is so freely and easily accessible. The danger comes in determining the intrinsic accuracy of data. An recent study has suggested that researching symptoms online is more likely to make one feel worse, and less informed. While this is of no surprise to physicians, here we seek to take a deeper look into why this is, and how we can better inform our patients.

How do search engines work?

To demonstrate how search engines work to generate content, we will use the following example; (while I wouldn’t recommend it) tea has been mentioned as a means of controlling bleeding. If you had an actively bleeding cut, and wanted to confirm that this was true, you would probably enter the following query: “does tea stop bleeding”.

The internet is a big place, and so search engines have to comb through endless amounts of data in an attempt to generate useful search findings. How descriptive the search is plays an significant role in this (too long a query, and you may get no data, while too short leaves you with too wide a net cast). Search engines will also tend to ignore overly common words or patterns of speech. For example, “does tea stop bleeding” – would only utilize the key words “tea, stop and bleeding”. As a result, the reader will capture all of the results that are most likely to incorporate those three words.

Search engines are designed (appropriately so) to provide one with the most relevant information for their query. As a result, search results are heavily biased towards whatever you’re looking for. Intuitively, we know this is why so many conspiracy theorists are able to find posts, blogs, websites etc. helping to corroborate their theory or belief.

Additionally, Google is often integrated into a lot of our technology and devices (emails, Google drive, search and even Google based phones) – and as a result, these integrated accounts may often bias the search results that Goole pulls for us. This is why you may often notice targeted advertisements on other platforms or social media. From an privacy aspect, this is also certainly concerning as Google/other search engines have no obligation to respect one’s privacy when you’re searching for something.

What about when it comes to healthcare?

Lets be honest, stories in which someone’s viral illness resolved within two or three days isn’t going to garner much attention online. However, cases or stories that revolve around the rare or unlikely condition are going to naturally be quite popular. This is a result of the availability bias; when an event is more emotionally or vividly recalled, individuals tend to give more power to that event.

As a result, when people search for medical advice online, they’re often seeing skewed and bias results, that are dramatic examples and deviations from the norm.

Lets take a look at an example, if you were to hit your head on a cupboard – most people would swear, rub their head and continue on with their day. However, if you’re used to looking everything up online or a particularly anxious person you may Google “head injury”, the first result you’ll find suggests:

While this may be reassuring to some individuals, others will read the bolded ‘traumatic brain injury’ – and come into the ER for further assessment, because ‘they’re not sure’.

While this may be reassuring to some individuals, others will read the bolded ‘traumatic brain injury’ – and come into the ER for further assessment, because ‘they’re not sure’.

While this is an isolated example, the internet is rampant with over-pathologizing pieces of information. When one searches “chest pain and shortness of breath” they’ll find an article with 26 rather concerning causes of chest pain.

So how can we help our patients and deal with Dr. Google?

The vast majority of patients presenting to the Emergency Department are not in extremis, and have often spent some time looking up their symptoms online (either at home, or during their wait). Often times, they suspect they have something benign, look up their symptoms, and are then worried about disease x – prompting their ED visit. Until you know that a patient is concerned about a particular diagnostic entity, you will be unable to alleviate their concerns. This comes down to one of the most powerful historical questions you can ask a patient; “is there anything that you are particularly worried about today”.

This question will often result in patients telling us about their Google searching – what they’re concerned about, and with the right physician education, you can help reassure the patient, and resolve their fears and concerns. Over-investigating, will not help to alleviate patient concerns, which is why having an discussion with your patients is perhaps the most useful thing one can do for them on their ED visit.

The other thing that is potentially very helpful is to provide patient’s with useful, evidence based information. Uptodate, for example, has patient information handouts that are typically quite robust. Additionally, just directing patients to the right sources of online information (that you know exist) will help to satisfy their curiosity and desire to look things up, while providing them with an reliable source of information.