Introduction

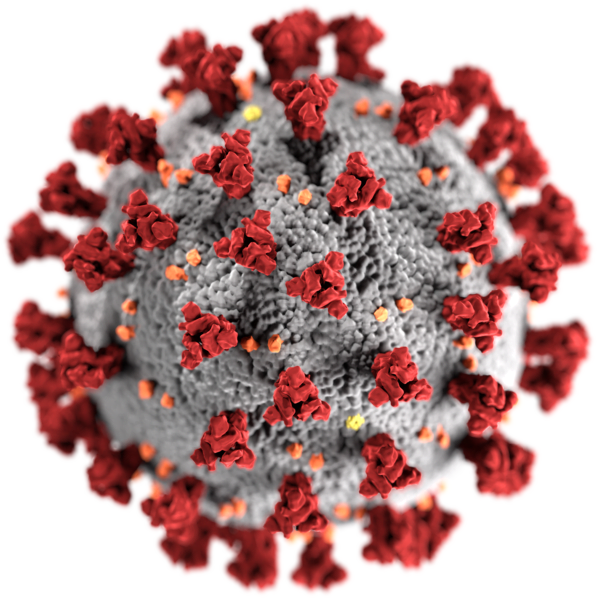

The novel coronavirus, known as COVID-19, was originally reported in a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan (China) near the end of 20191. Over the next 6 months, COVID-19 has emerged as the world’s newest pandemic disease with over 7 million cases worldwide1. The clinical presentation of COVID-19 is broad and classically involves fever, cough, dyspnea, malaise, and bilateral infiltrates on chest imaging. Less typical symptoms including diarrhea, myalgia, confusion, anosmia, and ageusia were also reported in the literature2. In terms of investigations, patients with COVID-19 infection may have lymphopenia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase level, and elevated inflammatory markers such as ferritin or C-reactive protein3. There has been increasing evidence that suggested COVID-19 is an endothelial disease with pro-thrombotic properties4. This article aims to discuss the hypercoagulability of COVID-19 infection and management of patients without evidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Pathogenesis of COVID-19 Hypercoagulability

The pathogenesis of COVID-19-associated hypercoagulability is not fully understood. Several studies proposed mechanisms where COVID-19 directly invades endothelial cells or indirectly causes cell injury via a cytokinetic inflammatory response or complement reactivation4. Patients with severe COVID-19 infection were found to have elevated fibrinogen and D-dimer levels5,6, though it was unclear whether this reflects hypercoagulability or an underlying inflammatory condition such as sepsis. Several studies showed that elevated D-dimer was associated with poor outcomes and prognosis in admitted patients with COVID-19 infection7,8. In contrast to disseminated intravascular coagulation that involves bleeding and reduced fibrinogen levels, the distinguishing feature of COVID-19 pertains to thrombosis formation and inflammation without significant consumption of coagulation markers5. A case-series study showed an increased risk for VTE, mostly pulmonary embolism, among intensive care unit (ICU) patients with COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) than those with non-COVID-19 ARDS, despite being on prophylactic anticoagulation9. Similar studies showed an incidence of VTE up to 30% within 7 days of admission among critically ill COVID-19 patients10–12.

Evidence of Anticoagulation in Patients with COVID-19 Infection

The management of COVID-19-associated hypercoagulability is evolving and challenging. According to the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis, all patients admitted to the hospital with medical and surgical concerns should receive standard VTE prophylaxis, unless contraindicated13. Low molecular weight or unfractionated heparin have been the main choice of therapy due to their shorter half lives. On top of its anticoagulation properties, heparin was noted to down-regulate interleukin-6 and its associated cytokinetic effects in a pre-clinical study14. However, the clinical utility of anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients without evidence of VTE was limited, especially in the outpatient setting. It was noted that therapeutic dose of anticoagulation should be considered for critically ill inpatients in the absence of VTE15. An early study in China showed that the use of therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with reduced 28-day mortality (40.0 vs 64.2%) in a subgroup of 97 COVID-19 patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy or significantly elevated D-dimer15. More recently, a retrospective study of 2,773 inpatients, of which 786 received therapeutic anticoagulation, showed that the use of therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with improved in-hospital mortality among intubated patients (29.1% vs 62.7%), after adjusting for multiple confounders16. However, patients who were fully anticoagulated were more likely to require mechanical ventilation than those without (29.8% vs 8.1%, p<0.001).

The Management of COVID-19 Hypercoagulability in the Emergency Department

Given the limited evidence, the practical management of COVID-19 hypercoagulability varies amongst centers and practitioners. The decision to initiate prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation should be based on numerous factors including patient hemodynamic status, need for respiratory support, and laboratory investigations such as D-dimer and fibrinogen levels. All patients admitted with moderate COVID-19 infection should receive a weight-adjusted prophylactic anticoagulation (refer to Figure 1 for dosing regimen), unless contraindicated17. Although controversial, COVID-19 patients who are hemodynamically unstable, with any signs of thrombosis, or signs of end-organ damage (e.g. on renal replacement therapy) may have a low threshold to receive therapeutic anticoagulation (refer to Figure 1 for inpatient anticoagulation algorithm)18. There is insufficient data to support the use of thrombolytics (e.g. tissue plasminogen activator) in critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection19. In patients with complex co-morbidities and abnormal coagulation panels, the thrombosis team may be consulted prior to initiation or augmentation of anticoagulation therapy. For patients with COVID-19 infection but hospitalization is not warranted, the use of anticoagulation is controversial in the absence of VTE due to very limited evidence. The National Institute of Health recommended against the use of prophylactic anticoagulation in outpatients unless there are other indications17. Currently there are no published randomized control trials to support the outpatient use of prophylactic anticoagulation.

Conclusion

In summary, COVID-19 is the newest emergent pandemic disease with unique hypercoagulable properties and multi-organ involvement including the respiratory system. Despite the study limitations, the current evidence recommends for prophylactic dose of anticoagulation for patients admitted with moderate COVID-19 infection without clinical findings of VTE, unless contraindicated. An observational study showed that therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with improved hospital survival within a selected population of critically ill patients. Patients with COVID-19 infection who do not require hospitalization should not receive prophylactic anticoagulation due to insufficient data. As more studies and trials unfold, emergency physicians should be vigilant for new developing guidelines to shape their clinical practice.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO Director-General’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. WHO Director-General’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. Published February 11, 2020. Accessed May 31, 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020

- 2.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. Published online February 7, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

- 3.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-1720. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

- 4.Magro C, Mulvey J, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. Published online April 15, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- 5.Panigada M, Bottino N, Tagliabue P, et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in Intensive Care Unit. A Report of Thromboelastography Findings and other Parameters of Hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. Published online April 17, 2020. doi:10.1111/jth.14850

- 6.Ranucci M, Ballotta A, Di D, et al. The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. Published online April 17, 2020. doi:10.1111/jth.14854

- 7.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844-847. doi:10.1111/jth.14768

- 8.Yin S, Huang M, Li D, Tang N. Difference of coagulation features between severe pneumonia induced by SARS-CoV2 and non-SARS-CoV2. J Thromb Thrombolysis. Published online April 3, 2020. doi:10.1007/s11239-020-02105-8

- 9.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. Published online May 4, 2020. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x

- 10.Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van H, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. Published online May 5, 2020. doi:10.1111/jth.14888

- 11.Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. Published online April 9, 2020. doi:10.1111/jth.14830

- 12.Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, et al. Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19 Patients: Awareness of an Increased Prevalence. Circulation. Published online April 24, 2020. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430

- 13.Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023-1026. doi:10.1111/jth.14810

- 14.Mummery R, Rider C. Characterization of the heparin-binding properties of IL-6. J Immunol. 2000;165(10):5671-5679. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5671

- 15.Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094-1099. doi:10.1111/jth.14817

- 16.Paranjpe I, Fuster V, Lala A, et al. Association of Treatment Dose Anticoagulation with In-Hospital Survival Among Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. Published online May 5, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001

- 17.National Institutes of Health . Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with COVID-19. Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with COVID-19. Published May 12, 2020. Accessed May 30, 2020. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/antithrombotic-therapy/

- 18.Klok F, Kruip M, van der, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145-147. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

- 19.Massachusetts General Hospital . Hematology Recommendations and Dosing Guidelines during COVID-19. Hematology Recommendations and Dosing Guidelines during COVID-19. Published April 30, 2020. Accessed May 30, 2020. https://www.massgeneral.org/assets/MGH/pdf/news/coronavirus/guidance-from-mass-general-hematology.pdf

Review with the Expert

Dr. de Wit is an Emergency Medicine/Thrombosis physician, researcher, and educator. She received dual specialty training in Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine in the UK. At the McMaster University, Dr. de Wit remains actively involved in research on the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism and coagulopathy.