What is the role of intravenous lipid emulsion in drug toxicity in the emergency department?

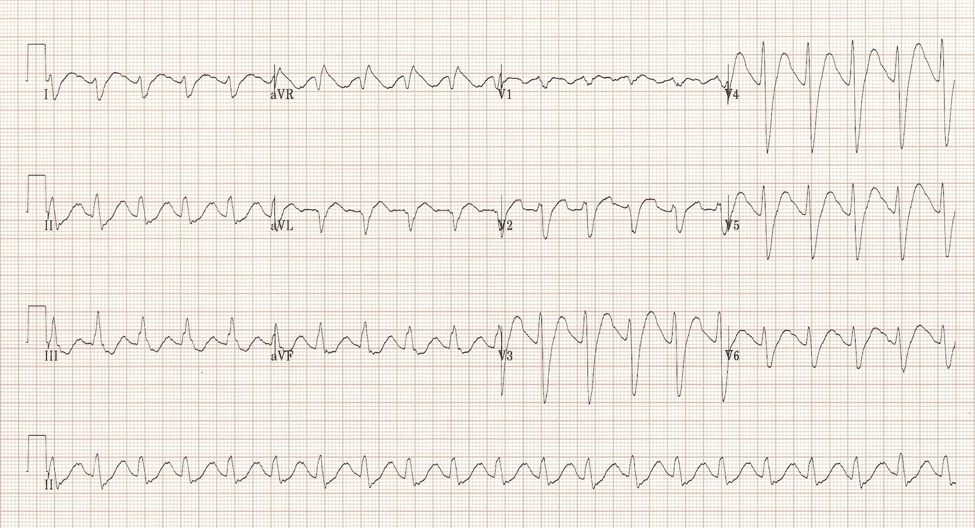

A 32-year-old male with depression and chronic neuropathic pain presents to your ED after an intentional overdose of 50 x 75 mg tablets of amitriptyline one hour ago. On exam, his blood pressure is 92/54 mmHg and his heart rate is 128 bpm. He is somewhat somnolent and gets rushed to your resuscitation bay from triage. His initial ECG shows a wide complex tachycardia (QRS duration of 122msec) with an R’ of greater than 3mm in aVR [Figure 1].

Figure 1: 12 lead ECG showing characteristic changes related to tricyclic antidepressant toxicity.1

Background

Intravenous lipid emulsion [Figure 2] has been around for a long time in the form of total parenteral nutrition and as a vehicle for lipophilic drugs; most notably propofol.2 Its use in toxicology dates to the late 1990s when rat models demonstrated a survival benefit in bupivacaine toxicity.2 This led to further studies involving dogs and eventually humans.

In 2006, the first case report was published in which an adult male patient was inadvertently injected intravenously with 20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine and 20 mL of 1.5% mepivacaine in the context of a brachial plexus block for rotator cuff repair. Shortly after injection the patient had a generalized tonic-clonic seizure followed by a 20-minute cardiac arrest with various cardiac dysrhythmias. Shortly before cardiopulmonary bypass was to be performed, 100 mL of 20% lipid emulsion was given intravenously, followed by 0.5 mL/kg/hr for 2 hours. Following this treatment, the patient was successfully electrically cardioverted. He was extubated 2.5 hours later.3

Since then, several other case reports have emerged and clinical guidelines have been developed for lipid emulsion therapy in severe local anesthetic toxicity.4–6 Case reports continue to be published highlighting lipid emulsion therapy for an ever-expanding number of drug toxicities including non-dihydropyridine calcium channel clockers, beta blockers, bupropion, lamotrigine, and tricyclic antidepressants.4

Figure 2: 100mL bag of 20% lipid emulsion. (Image courtesy of James Heilman, MD via Creative Commons license).

How does it work?

The short answer is, we don’t know. There are two prevailing theories that are most often quoted:

- Partitioning or “lipid sink” theory: Partitioning is thought to work by providing a “sink” for which lipophilic xenobiotics can reside thus removing them from accessibility to end organ receptors.2

- Enhanced cardiac metabolism theory: In situations of myocardial depression due to drug toxicity, it is thought that myocardial contractility might be improved by providing extra substrate in the form of fatty acids.2

When should I use lipid emulsion therapy?

At this point in time, there is no FDA approved indication for lipid emulsion therapy in drug toxicity.2 Formal guidelines do exist for lipid emulsion use in local anesthetic toxicity and the best evidence is for bupivacaine toxicity.5,6 Lipid Rescue (lipidrescue.org) offers case reports for lipid emulsion use in a multitude of drug toxicities including tricyclic antidepressants, cocaine, and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.7

When it comes to severe drug toxicity we are often dealing with a patient with unstable hemodynamic parameters and a poor prognosis. Lipid emulsion therapy can be considered as a last resort in drug toxicity when:

- appropriate high quality supportive care has been administered,

- there are no further conventional therapy options,

- the patient continues to be unstable or in cardiopulmonary arrest,

- and the offending drug is lipophilic (i.e., has an octanol-water partitioning coefficient of logP > 2).4

An in-depth review of octanol-water partitioning coefficients is beyond the scope of this article. See Table 1 for several reference values.

Table 1: A selection of lipophilic medications and their partitioning coefficients.2

What dose should I be giving?

This is where it gets challenging. Virtually all the case reports mentioned above have variations regarding dosing and every drug class has unique factors such as lipophilicity, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. Fortunately, the protocols published by the American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA) and the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) are quite similar.5,6

ASRA recommends the following:

- Lipid Emulsion Therapy (20%)

- Bolus 1.5 mL/kg of lean body mass (height in cms – 100) over 1 min

- Continuous infusion to follow at 0.25 mL/kg/min

- Repeat bolus 1-2 times for persistent cardiovascular collapse

- Double infusion rate to 0.5 mL/kg/min if BP remains low

- Continue infusion for at least 10 mins after circulatory stability

- Recommended upper limit of 10 mL/kg over the first 30 mins

Simplified protocol based on 70kg person:

- 20% lipid emulsion 100mL bolus over 1 min

- 18mL/min infusion afterwards

Don’t forget that these are guidelines based on local anesthetic toxicity. Case reports have wide dosing ranges and infusion times of up to 19 days depending on the offending drug!9

Are there any adverse effects?

Most of the evidence regarding adverse effects from lipid emulsion infusion comes from the use of total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Infusion rate and total infused dose are associated with adverse reactions.10 TPN guidelines recommend:

- maximum infusion rate of 0.55 mL/kg/min and

- maximum total daily dose of 10 mL/kg/day;

- compliance with these guidelines makes adverse effects a rare occurrence.10

Nonetheless it is important to be aware that adverse effects including hypoxia, ARDS, fat overload syndrome, pancreatitis, and fat emboli can occur and that, when we venture into higher dose regimens than recommended, the risk of adverse effects increases.10,11

Case resolution

Unfortunately, your patient has had 3 episodes of cardiac arrest requiring defibrillation and repeated doses of sodium bicarbonate. In conjunction with your local poison centre, you choose to go ahead with lipid emulsion therapy given several recent case reports [Table 2] and a new guideline regarding lipid emulsion therapy in amitriptyline toxicity.9,10,12–15 You administer a 100mL IV bolus of 20% lipid emulsion followed by an infusion of 18mL/min. Your patient has return of spontaneous circulation with sinus rhythm at a rate of 135 bpm and a QRS of 132 msec requiring a continuous sodium bicarbonate infusion. Your intensive care colleagues arrive in the resuscitation bay and admit the patient to ICU.

Table 2: Case reports involving human ingestions of toxic Amitriptyline doses treated with intravenous lipid emulsion therapy in the last 10 years.9,13–15

Summary

- Lipid emulsion therapy has provided an exciting avenue of therapy with potential survival benefit in severe drug toxicity

- Most of the evidence is from case reports which are subject to several biases including positive reporting bias

- The ASRA guidelines provide the most agreed upon guidance for dosage (100mL 20% lipid emulsion bolus followed by 18mL/min infusion for 30 mins)

- Consider lipid emulsion therapy in patients presenting with refractory cardiovascular collapse secondary to drug toxicity where the offending agent is lipophilic and there are no further viable options for treatment

- Adverse effects are rare if your infusion rate is less than 0.55 mL/kg/min and your daily dose is less than 10mL/kg

Recommended resources

http://lipidrescue.org

https://www.aliem.com/2015/lipid-rescue-why-arent-we-using-it/

http://lifeinthefastlane.com/intralipid-myth-or-miracle/

http://www.emdocs.net/lipid-emulsion-therapy-tox-emergencies/

* Fictitious case based on existing literature.

This post was copy-edited by Michael Bravo (@bravbro).

[bg_faq_start]References

Intralipid: The Rule of Threes

One of my colleagues used to have a rule of threes: tell me three things in the differential, one - the most likely, two- the most lethal, and three - the most interesting.

Before considering using Intralipid I propose another round of three questions one might ask:

1. Have I maximized conventional therapy? Have I aggressively resuscitated cardiogenic shock with crystalloid, alkalization where indicated, and at least maximal doses of a vasopressor? Have I maximized status seizures with intubation, and the addition of Propofol or barbiturates?

2. Is the patient likely to deteriorate further based on what I know about the amount ingested, and natural history of this drug overdose? Clearly an early rapid deterioration may require Intralipid, but a slow decline over 24 hours may just warrant either upward adjustment of therapy, or acceptance of suboptimal goals of therapy such as a MAP slightly less than 65 mmHg. Other metrics may need to be assessed - do signs of vital organ perfusion, urine output and CNS function, remain normal?

3. Is the putative substance responsible likely to be lipid soluble? While it may not be possible to know the partitioning coefficient for every substance, an assumption may be that if the drug easily crossed the blood brain barrier causing CNS effects, it more likely than not is lipid soluble.

In the attached case presentation 5 medications for which supportive evidence suggests a benefit have these listed (Medication/Partitioning coefficient[logP]):

-Bupivicaine - 3.9

-Amitriptyline - 5.04

-Bupropion - 2.61

-Verapamil - 2.31

-Propanolol - 3.09

An easy way to remember these may be the last of a rule of 3’s:

-Sodium Channel Blockers (Tricyclic antidepressants, Local anesthetics, Lamotrigine, Class I antidysrhythmics)

-Beta-blockers (The exception here is only atenolol is highly water-soluble)

-Calcium Channel Blockers (Mostly the NON dihydropyridines)