All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

CanMEDS Roles addressed: Expert, Leader

Case Description

You have just diagnosed a 55-year-old male with an acute proximal deep vein thrombosis in the emergency department. The event was unprovoked, and he has symptoms of leg swelling and pain. He is otherwise healthy and takes no regular medications. He has no symptoms suggestive of PE, and his blood pressure and oxygen saturation are normal.

You note incidentally that he has microcytic anemia, with hemoglobin (Hb) 110 g/L and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 79 fL. He denies any rectal bleeding or melena, and there is no hemoptysis or hematuria. His last bloodwork from 12 months ago demonstrated Hb 138 g/L and MCV 90 fL.

He tells you that he recently had a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) ordered by his family doctor that came back with a POSITIVE result. You confirm this upon reviewing his regionally linked electronic patient record.

Now you’re stuck, right? How reliable is the FOBT as an indicator of acute bleeding? And if the result is positive, is it safe to use full dose anticoagulation?

Main Text

How reliable is the FOBT as an indicator of active GI bleeding in the acute care setting?

The FOBT is a screening test whose main (and really, only) purpose should be to screen for colorectal cancer. It is not intended to be a diagnostic test for colorectal cancers or gastrointestinal bleeding. Notwithstanding, 8-30% of FOBT tests are performed to assess for causes for anemia or iron deficiency. This is an inappropriate application of this test; in symptomatic individuals (including patients such as ours who have overt anemia) the FOBT likely postpones endoscopies investigations, leading to diagnostic delays while increasing cost 1.

Even in patients with visible blood or melena, the results of FOBT lack sensitivity and specificity. In a recent JAMA Rational Clinical Examination systematic review 2, the presence of fecal occult blood was not diagnostic of upper GI bleeding requiring urgent intervention. Meanwhile, fecal occult blood results are not particularly sensitive, meaning that you can’t rely on a negative FOBT to rule out active GI bleeding either 2. Instead, several clinical factors increased the likelihood of upper GI bleeding – patient reports of melena, melena stools on examination, nasogastric lavage with blood or coffee grounds, and a serum urea : creatinine ratio or more than 30. Finally, a recent audit in acute care settings determined that FOBT results in patients with anemia or suspected bleeding were not correlated with real-life decision-making – two-thirds of patients with positive results did NOT undergo further GI investigations, and many people underwent endoscopy even before the FOBT results were reported 3.

In summary, the FOBT has limited utility (if any!) in the emergency department in determining whether there is active bleeding because it is validated primarily as a screening test, and lacks sensitivity and specificity. These results have limited bearing in determining whether anticoagulant therapy is likely to be safe.

But the result is positive. Is it safe to prescribe full dose anticoagulation?

The likelihood that this patient will bleed when provided full dose anticoagulants is difficult to predict as the cause for his microcytic anemia is uncertain. However, as outlined above the results of an FOBT test should not have an impact on your judgment of whether your patient has an active bleeding source. Instead, you would make a judgment about anticoagulation based on clinical risk factors and patient history.

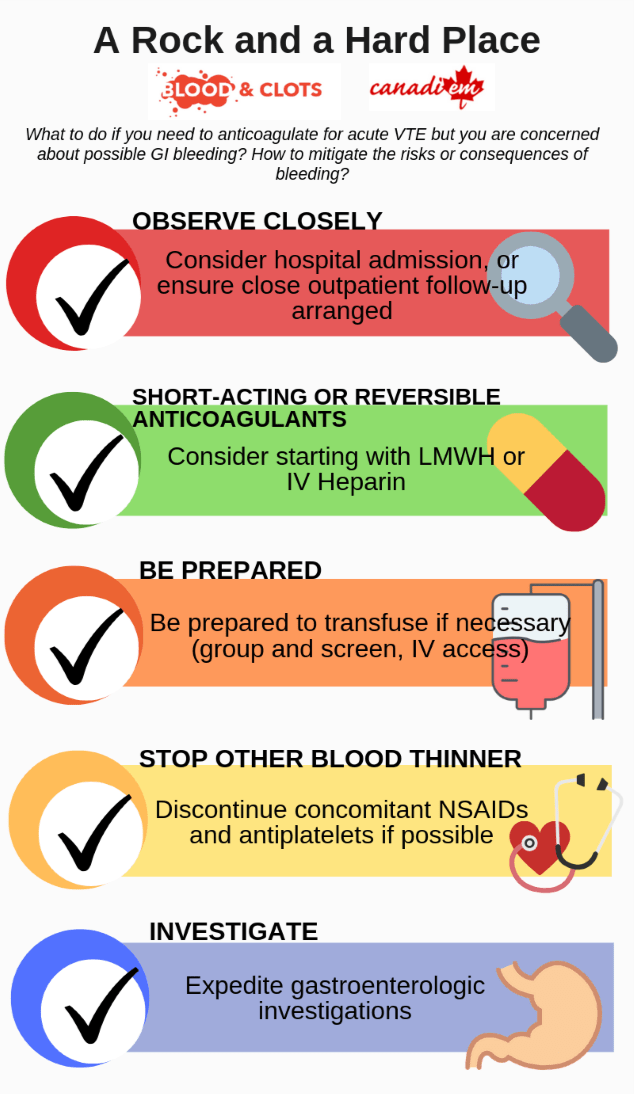

In this situation, given that this patient has an acute DVT, he merits anticoagulation to improve symptoms, reduce risk of local clot extension, reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism, and reduce mortality. If there is a clinical suspicion for a possible bleeding source but anticoagulation is needed, there are no consensus- or evidence-based guidelines about how to handle this challenging situation. However, in my clinical experience/opinion, steps to mitigate the risk or consequences of bleeding would include:

- Close observation: either hospital admission (if overt bleeding or bleeding risk factors), or close outpatient follow-up.

- Choose short-acting, reversible anticoagulants: Consider initially using low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH), as they have shorter half-lives than DOACs or Warfarin and are potentially reversible with protamine sulphate (UFH is fully reversible, LMWH is partially reversible)

- Be prepared: Prepare to transfuse if necessary (group and screen, intravenous access)

- Stop concomitant antiplatelet medications or NSAIDs: these medications will increase the risk of bleeding, and should be stopped if possible. This may require discussion with a cardiologist if there is a competing indication for the antiplatelet agent 4

- Investigate: Expedite gastrointestinal investigations / endoscopy to rule out or treat an active bleeding source 5

Case Conclusion

Despite this patient’s anemia and positive FOBT, you decide to start him on full dose low molecular heparin as there is no history of overt bleeding. He is discharged with close outpatient follow-up, with strict instructions to return to the Emergency Department if there are signs of overt bleeding. He undergoes a colonoscopy three days later and is found to have adenocarcinoma of the colon. He decides to remain on low molecular heparin during his investigations and treatment for his cancer.

Main Messages

- The FOBT is a screening test for colorectal cancer screening, not a diagnostic test for GI bleeding. As such, results lack sensitivity and specificity for active GI bleeding, and the test should not be done in the acute hospital setting as implications of results are unclear

- If you have a suspicion for an active bleeding source in someone with an acute VTE, consider monitoring the patient closely either via hospitalization or close outpatient follow-up. Also consider using shorter-acting, reversible anticoagulants while observing for stability

All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

This post was reviewed by Teresa Chan, Anson Dinh and copyedited by Rebecca Dang.