Approaching the complaint

Occipital neuralgia is a headache disorder characterized by shooting neuropathic pain secondary to greater or lesser occipital nerve pathology. The diagnosis should be considered in a patient presenting with the following:

- Unilateral or bilateral pain originating at the skull base

- Sharp, shooting, lancinating, or burning pain that radiates forward along the dermatomes supplied by the greater or lesser occipital nerves

- Paroxysmal pain lasting seconds to minutes

- Dysesthesia or allodynia over the affected area

- Positive Tinel’s sign over the origin of the greater occipital nerve near the skull base

Image reprinted with permission

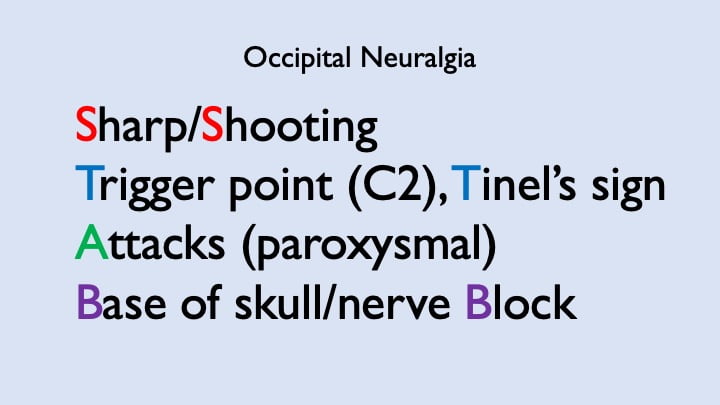

We propose the following useful mnemonic to assist in making a diagnosis:

STAB

Sharp/Shooting

Trigger point (C2), positive Tinel’s sign

Attacks (paroxysmal)

Base of skull/nerve Block

Additionally, patients may complain of pain with neck rotation or direct pressure over the nerve trunk, as may occur when sleeping on a pillow (“pillow sign”).1,2

Skimming the textbook

The condition is attributed to nerve compression caused by sub-occipital muscle hypertrophy, tensing, or spasm.2 Approximately 90% of cases of occipital neuralgia involve the greater occipital nerve (GON), while the remaining 10% of cases are thought to be attributable to lesser occipital nerve (LON) pathology.3

Limited literature exists on the affected demographic; however, one Dutch study demonstrated an incidence of 3.2 per 100 000 with slight, non-statistically significant female dominance.3

Differential diagnosis

The headache described in occipital neuralgia should be distinguished from those caused by referred pain from the atlanto-axial or facet joints, cervicogenic, and other primary headache disorders.4 Masses, infection, and congenital anomalies, including Chiari malformations, should be considered and, if clinically relevant, ruled out through radiographic investigation such as open-mouth C-spine x-rays or CT of the craniocervical junction.4 Features characteristic of neuralgia (lancinating, burning, intermittent pain) may help to distinguish occipital neuralgia from the nociceptive-type (constant, aching) pain underlying the numerous differential diagnoses, although patient descriptions may have significant overlap.4

Treatment

While evidence-based treatment of occipital neuralgia remains elusive, pain relief with occipital nerve block may be both diagnostic and therapeutic.2–4 A nerve block may consist of local anesthetic alone (e.g. lidocaine or bupivacaine, with or without epinephrine), or include injectable steroid (e.g. depo-medrol). The needle should be inserted approximately 2cm inferior and 2cm lateral to the occipital prominence, at the emergence of the greater occipital nerve.2,4 Of note, false-positive results may occur with primary headache disorders such as migraine, cervicogenic, cluster, or tension-type headaches.2–4

Relief provided by the nerve block may persist for hours to several weeks, at which time the procedure may be repeated in office.2,4 Alternatively, initial conservative management may involve any of a number of modalities to reduce muscle tension and improve neck posture, including warm or cold compresses, massage, and physiotherapy.2–4

Pharmacotherapy may lessen the frequency and severity of acute episodes, including anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications (NSAIDs, acetaminophen), anti-epileptics (gabapentin, pregabalin), and tricyclic antidepressants; however, there is minimal published evidence to support the efficacy of these interventions.2–4 Anecdotal evidence suggests therapeutic benefit with gabapentin 300-600mg qhs or nortriptyline 30-50mg qhs.2

This post was copyedited and uploaded by Josiah Butt