In an attempt to better understand the inefficiencies in the emergency department, Kristian Simsarian, a renowned professor in the field of design, feigned a foot injury.1 With a video camera hidden, he documented his experience from start to finish.1 The insights he brought back to his team were both expected and sobering.1 The video tape showed hours of Simsarian staring at a monotone ceiling with no idea of what to expect.1

In the midst of technological advances, clinicians and health service providers have begun to wonder whether computers will cause us to veer away from the human-centered approach to medicine. On the other hand, new technology can be used to improve the patient experience. How do we address issues that are commonly faced by physicians in the emergency department while giving adequate weight to the patient experience? Importantly, how do we make sure that we are improving on aspects of patient care that are valuable to patients themselves?

The patient experience is often seen as distinct from clinically relevant outcomes. We are trained to use the best available evidence to evaluate which drugs to use, when to admit, and when to intervene. It is rare to think of changes to the patient experience as being an intervention in and of itself. An interesting study published in Science in 1984 showed that patients recovering from cholecystectomy surgeries with window views of natural scenery had shorter postoperative stays than those who faced brick walls.2 It is interesting that a simple change in the environment can change the course of the patient’s hospital admission. The range of possible changes do not need to be drastic or cutting edge to make a difference–we only need to listen to patient groups about their frustrations and their identification of opportunities for improvement. It is integral, then, that patients are central to the innovation process and their subjective experiences in healthcare are made a priority.

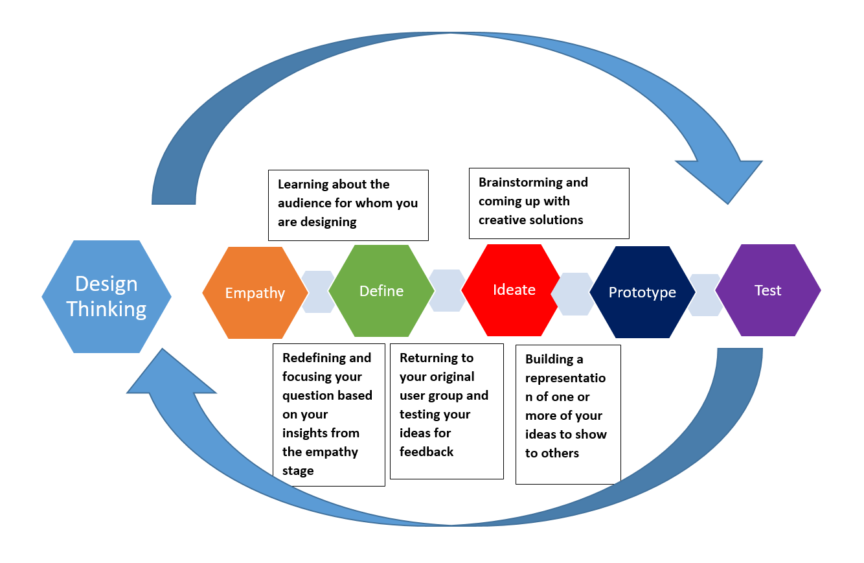

How do we improve healthcare while putting patients at the forefront of decisions? Perhaps a more reasonable question is to ask how we improve healthcare without the patient perspective? How does healthcare catch up in their provision of a “customer” centered experience while still providing high-quality care? A widely used approach for brainstorming and implementing new solutions in the business and technology world is known as design thinking.3 The process of design thinking involves empathizing with the client, defining a problem, sharing ideas, prototyping solutions, and testing what works.4 Importantly, it puts the client or patient’s experience at the core. There has been increasing interest in incorporating design thinking into medicine, with 95% of the NEJM Catalyst Insight Council supporting its use in the healthcare industry.5–7

The emergency department is a complex work environment in which clinicians need to make quick decisions with limited information. Being in the ED is a source of anxiety and confusion for patients who are already fearful for their health. Workflow issues, overcrowding, and lack of communication can further exacerbate this experience. Design thinking has been used in the literature to improve communication in the ED between patients and providers, with the end result being 33 training sessions with 289 clinicians on improving care in the ED.8 Importantly, in this study, patient safety reports were integral in identifying issues that patients cared about and could be addressed.8 At Thomas Jefferson University, medical student teams were tasked with applying design thinking principles to common ED problems, including patient-physician identification and managing patient expectations.8 Both students and faculty mentors reported a better understanding of patient experience design and clinical workflow optimization.9

As a medical student at McMaster, I have been involved in leading a program called MedxEng. This is a collaboration between the medical school, engineering school, and the St. Joseph’s Hospital patient interest group. In this semester-long program, groups of medical and engineering students learned design thinking principles in didactic sessions before moving on to interviewing patient advisors. Several interesting ideas have arisen in the two years since its conception, including an app that connects patients in inpatient wards to decrease feelings of isolation while in hospital. The patient advisors were enthusiastic about the results of the projects and their potential implementation.

In our prior example, Simsarian was a healthy man with no real injury. Despite this, the sheer number of hours spent in isolation, left with no information, and in the setting of an overly crowded and rushed environment was enough to evoke fear and anxiety. How would this differ for the elderly patient presenting with delirium, the refugee who does not understand English, or the patient with an intellectual disability? Are our emergency departments created to optimize their experience?

Let’s say we use Simsarian’s video tape in our design thinking process. The problem at hand may be defined in several ways–lack of information, prolonged wait time, or isolation. Let’s say that lack of information was identified as the largest concern for Simsarian. Going from there, we could create several solutions to disseminate information in a timely manner. A solution may be an app that allows for quick communication between the ED physician and the patient.

We would then present this app to Simsarian and other patients. Would this address your problem, is it accessible, and how can it be improved? By presenting the same solution to multiple patients who share the same frustration, it could be tailored to encompass a larger audience. The app may integrate translation services. It may allow information dissemination with the patient’s family. Perhaps the app is not the solution at all and we have to start from scratch.

Design thinking has shown exciting potential in innovating the healthcare sphere. There are several opportunities to use this approach in quality improvement and medical education. This change in focus can begin as early as at the undergraduate medical level. Importantly, we can empower both the future physician and the patient to see inefficiencies as potential avenues for future quality improvement rather than an unfortunate failure of the healthcare system.

This post was copy-edited by @alexsenger.

References

- 1.Collective D. An Exercise In Empathy – Going Undercover To Discover What It’s Like To Be The User. Medium. Published 2020. Accessed June 6, 2020. https://medium.com/@DCollective_BER/an-exercise-in-empathy-going-undercover-to-discover-what-its-like-to-be-the-user-93fe61845b5a

- 2.Ulrich R. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 1984;224(4647):420-421. doi:10.1126/science.6143402

- 3.Beckman SL, Barry M. Innovation as a Learning Process: Embedding Design Thinking. California Management Review. Published online October 2007:25-56. doi:10.2307/41166415

- 4.Steinke GH, Al-Deen MS, LaBrie RC. Innovating Information System Development Methodologies with Design Thinking. In: ; 2017.

- 5.McLaughlin J, Wolcott M, Hubbard D, Umstead K, Rider T. A qualitative review of the design thinking framework in health professions education. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):98. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1528-8

- 6.Ku B, Shah A, Rosen P. Making design thinking a part of medical education. NEJM Catalyst. 2016;2(3).

- 7.Kim S, Myers C, Allen L. Health care providers can use design thinking to improve patient experiences. Harvard Business Review. Published August 31, 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/08/health-care-providers-can-use-design-thinking-to-improve-patient-experiences

- 8.Aaronson E, White B, Black L, Sonis J, Mort E. Using Design Thinking to Improve Patient-Provider Communication in the Emergency Department. Qual Manag Health Care. 2020;29(1):30-34. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000239

- 9.Zhang X, Pugliese R, Hayden G, et al. Innovation per DiEM (Design in Emergency Medicine): A Longitudinal Medical School Design Co-Curriculum Led by Emergency Medicine Mentors for Real Emergency Department Issues. WestJEM. 2018;19(4.1). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8xn2g89d

Reviewing with the Staff

The paradigms of providing high-quality healthcare are indeed changing. So too are the tools we will be asked to use to make our environments, processes and teams more patient-centric. For many years, the “quality” of care has been defined by the effectiveness of the care. In other words, it has been governed by evidence of an increasingly demanding and robust nature. Despite our ability to provide the highest level of evidence to patients in our care, we have often had experiences where patients remain unhappy, unheard or unable to guide their own care.

The constructs provided by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in “Crossing the Quality Chasm” (2001) provide us a lens through which we may view the problem of effectiveness and the patient experience. They outline the 6 domains of high-quality care which include Safety, Timeliness, Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity and Patient-Centeredness. We can see here that the classic RCT design often does little for efficiency, timeliness and, perhaps most of all, patient-centeredness. The field of Quality Improvement (QI) has taken to improving these domains of quality and has broadly recognized efforts to improve non-traditional focus areas of health care provision.

Despite this reality, QI must also recognize where it expresses limitations. Surely patient-centeredness is more than including a few patient representatives on a working group as part of a GRADE process. And it is likely more than a broad stakeholder engagement with patients where they are key decision makers at every step of the process. In these instances where we are looking to improve our healthcare systems, QI must look to tools traditionally outside of its “envelope”. It strikes me that design thinking, along with its cousin Experience Based Co-Design, have much to teach us around processes that are designed by patients, according to their values.

I would be both shocked and disappointed if health systems, health teams and individual units did not begin to use Design Thinking as a fundamental redesign strategy in the coming years. Our challenge in healthcare is that we like to talk about things for 7-10 years before we actually use them or practice them. The implementation of design thinking in healthcare redesign will take strong leadership from health system leaders and advanced skillsets by those individuals who will be the change process owners. Articles that call us to think differently, from the patient perspective, are much needed in healthcare. My aspiration is to have several medical students and residents training in these concepts in the coming years to bring change to healthcare delivery.