Electrolyte imbalances like hyponatremia can be the cause of a variety of vague complaints. At the same time, patients may present with electrolyte abnormalities that are asymptomatic and are incidental findings on bloodwork. Here’s an approach to deciding when and how to treat hyponatremia in the emergency department. We also thank Drs. Joel Topf (@kidney_boy) and Dr. John Neary (@jddneary) for their valuable input on this article!

The Case

Marjorie, an 83-year-old female, presents to the ED with a chief complaint of progressively worsening weakness and fatigue over the past week, associated with a loss of appetite, nausea, and occasional confusion. Marjorie denies shortness of breath, chest or abdominal pain, cough, pain or swelling in her legs, other neurological symptoms, fever, vomiting, or diarrhea.

Her son reports that Marjorie lives independently at home and is usually active, enjoying cooking for her family and spending time outdoors. Over the past week she has “not been herself”, unable to get out of bed, taking no interest in her usual activities, and at times confused about where she is.

Her medical history is significant for hypothyroidism, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. According to family, she was hospitalized for three days a few months ago due to “dehydration”, at which time she was given “fluids”. No further details are available. Her medications include L-thyroxine, a statin and a thiazide diuretic.

Vitals are normal. On exam, Marjorie is weak and is unable to sit up without assistance. Strength testing reveals bilateral weakness in the arms and legs. A walk test is not attempted. No focal neurological deficits are noted. Cardiac, respiratory, and abdominal exams are normal.

Investigations are ordered and results reviewed.

- Electrolytes: sodium 110 mmol/L, potassium 3.4 mmol/L, chloride 76 mmol/L, bicarbonate 24 mmol/L

- Glucose: 4.3 mmol/L

- CBC: Normal

- TSH: Normal

- Urinalysis: Normal

- Troponin I: Normal

- CXR: Normal

- ECG: Normal

Definition, classification, and causes of hyponatremia

Hyponatremia occurs when there is an excess of water relative to sodium, defined as a serum sodium concentration below 135 mmol/L. Specific cut-offs can vary between guidelines and other sources1–4

- Mild – 130-135 mmol/L

- Moderate – 120-129 mmol/L

- Profound/Severe – <120 mmol/L

Hyponatremia can also be classified as acute (having developed over <48 hours) or chronic.1 However, although there is some correlation between duration and severity, recent treatment algorithms classify hyponatremia by severity of symptoms. which more appropriately guides treatment in most cases4 (see Treatment below).

- Severe: cardiorespiratory arrest, seizures, coma, deep somnolence

- Moderate: nausea, confusion, headache, vomiting

In adults, the most common causes of hyponatremia include thiazide use, SIADH, primary polydipsia, and water intoxication (intentional or unintentional). In infants and children, GI fluid loss and unintentional ingestion of excessive water are most common5. Besides thiazide and SSRIs, medications that can cause hyponatremia include other anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, anti-epileptics, and NSAIDs1.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Why does this matter? Pathophysiology and Complications of Hyponatremia

Left untreated, hyponatremia can be a life-threatening condition. Hypotonic plasma leads to a shift of water from the extracellular to the intracellular space, leading to brain edema and a resultant increase in intracranial pressure. This can lead to coma, seizures, cardiorespiratory distress, brain herniation, and death1,2.

However, hyponatremia that has developed gradually allows cells to adjust to the hypotonic environment by reducing intracellular concentration of solutes. In these patients, it is overzealous rapid treatment, rather than lack of treatment, that poses the most danger.

It is estimated that 3-6% of patients present to the ED with hyponatremia, which is associated with higher mortality and increased length of hospital stay.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of hyponatremia depend on the level of sodium deficiency and whether the hyponatremia developed acutely or over a longer period of time5. Signs and symptoms include2:

- Nausea, vomiting

- Headache

- Confusion

- Seizures

- Abnormal somnolence, coma

- Cardiorespiratory distress

- Hiccups

- Ataxia, falls

- Slow decision making

Brain cells adjust to hyponatremia within 24-48 hours by reducing intracellular concentration of other solutes. Therefore, in many cases, patients with acute severe hyponatremia can be expected to present with more severe symptoms than those with chronic hyponatremia1.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Investigations

The presence of hyponatremia is established by the standard serum electrolyte test. Caution must be taken of other plasma abnormalities or sampling errors that can mimic hyponatremia:

- Pseudohyponatremia – an elevation in non-osmolar plasma proteins or lipids, leading to a falsely low sodium reading. If pseudohyponatremia is suspected, direct ion detection can be used through the ABG lab.

- Euosmolar/Isotonic or hyperosmolar/hypertonic hyponatremia – presence of other effective osmoles (e.g. glucose, mannitol, glycine), leading to water being pulled into the plasma and lowering the serum sodium. These patients have no clinical manifestations of hyponatremia because they do not have hypoosmolar plasma.

Hyponatremia and Volume Status

Additional testing can be performed to identify whether the hyponatremia is hypo-, hyper-, or euvolemic. which is crucial in identifying the underlying etiology and guide treatment. Failure to identify the underlying cause of hyponatremia can lead to therapy that harms the patients4.

| Hypovolemic | Euvolemic | Hypervolemic | |

| Definition | Loss of sodium and relatively lesser loss of body water | Normal total body sodium and excess total body water | Increased sodium with relatively greater increase in body water |

| Etiologies | Vomiting, diarrhea, diuretic use | Syndrome of inappropriate anti diuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), drugs (most frequently SSRIs), hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, primary polydipsia, Water intoxication (e.g., endurance athletes), beer potomania, MDMA use | Heart failure, kidney disease (e.g., advanced chronic kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome), cirrhosis |

| Signs, Symptoms | Volume depletion (orthostatic hypotension, decreased skin turgor) | Absence of signs and symptoms of hypo- or hypervolemia. | Edema, ascites, pulmonary effusion |

| Investigations | Urine sodium excretion (<20-30 mmol/L), fractional excretion of uric acid, trial of volume expansion | Urine sodium excretion (>20-30 mmol/L), trial of volume expansion | Urine sodium excretion (<20-30 mmol/L), Elevated BUN |

| Notes on Treatment | Correction of volume deficit, treatment of underlying disease, avoiding over-rapid correction. In case of cerebral salt wasting, do NOT restrict fluids See guidelines for recommended treatment by specific underlying pathology4 | Chronic SIADH most common cause, in which case isotonic saline is not effective and fluid restriction is first line therapy. Patients with severe symptoms require correction of sodium levels. Those with milder symptoms may only require treatment of the underlying etiology. See guidelines for recommended treatment by specific underlying pathology4 | Causes are often chronic, increasing risk of overcorrection. HF patients with severe symptoms require hypertonic + diuretic. Focus on treating underlying cause. Increase sodium levels in patients with severe symptoms in most cases. Vaptans can be used where fluid restriction does not work, except in some cases of liver cirrhosis. See guidelines for recommended treatment by specific underlying pathology4 |

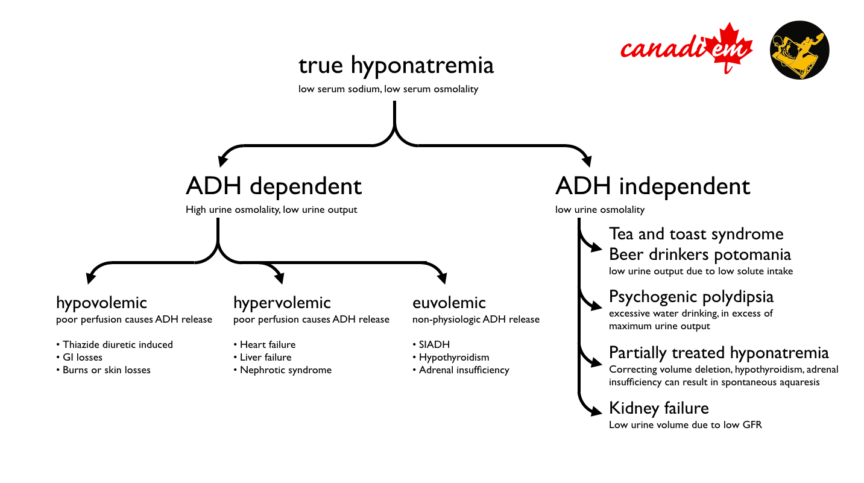

Differentiating between these types is not always possible. Additional discussion of the specific treatments for hyponatremia in special cases is covered in additional detail in the guidelines and elsewhere1,2,4,5. Dr. Joel Topf, a nephrologist and the author of the staff review of this article, also provided a flowchart of his basic approach to hyponatremia.

Treatment

If the decision is made to go ahead with treatment, keep the following principles in in mind.

- Decide whether treatment is required in the ED at all. Treatment should be focussed on the individual patient, not lab values. Not all patients presenting to the ED with hyponatremia require rapid treatment, particularly in cases where the hyponatremia is thought to have developed gradually, with effective patient compensation, manifesting with no or sub-acute symptoms.

- Set up for success – if possible, weigh your patient in order to have as accurate an estimate of total body water as possible. Also, have an idea of what tonicity saline is available at your site.

- Go slow – when attempting to acutely correct hyponatremia, aim for sodium correction of 5-8 mmol/L over the first 24 hours, with an absolute limit of 10 mmol/L in 24 hours1,2.

- Overly rapid increase in sodium levels, particularly in patients with chronic hyponatremia, can lead to osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS), a profoundly debilitating condition. In 2011, a patient successfully sued her physician and nurse for overcorrection of sodium levels, leading to ODS and lifelong disability6.

- In all cases, avoid overcorrection of more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours.

- Water diuresis (i.e. high urine output) is often the first sign of impending rapid correction (e.g. primary polydipsia, correction of hypovolemia, resolution of thiazide diuretic effect). The development of water diuresis should prompt careful monitoring for a rising serum sodium

- Cue up medicine – while treatment for moderate to severe hyponatremia starts in the ED, patients may have to be admitted until symptoms regress. However, patients with asymptomatic, mild, and sometimes even moderate hyponatremia often do not require admission.

Treatment in the ED is generally guided by severity of symptoms. The below is a synthesis of guidelines and other sources, which can vary in their recommendations. Treatment of hyponatremia outside the ED is beyond the scope of this article.

Severely symptomatic2

- IV bolus 150 ml 3% hypertonic over 20 min, check serum sodium

- Repeat IV bolus 150 ml 3% hypertonic over 20 min, check serum sodium

- Provide up to two additional 150 mL boluses, spaced 20 minutes apart, until a 5 mmol/L increase in sodium concentration is reached

- If symptoms improve after a 5 mmol/L increase is achieved, stop infusion and attempt to treat underlying cause

- Monitor sodium concentration every 6 hours

- If symptoms do not improve continue IV 3% hypertonic saline at a rate leading to an increase of 1 mmol/L/hr.

- This rate depends on each patient’s weight and percentage body water (see appendix for formula and example calculation)

- Monitor sodium concentration every 4 hours

- Do not exceed an increase of more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours.

Moderately symptomatic1,2

- Where possible, discontinue use of medications that can worsen hyponatremia

- Treat underlying condition, if known. Some causes (e.g. primary polydipsia) will respond to doing nothing beyond fluid restriction, and acute treatment with hypertonic saline will expose the patient to unnecessary risk of harm.

- If correction is not expected by treating underlying condition, consider

- IV bolus 150 ml 3% hypertonic over 20 min

- 3% hypertonic infusion solution at 0.5 mL/kg/h until an increase of 5 mmol/L in 24 hours is achieved.

- Check sodium concentration at hours 1, 6, and 12.

- Do not exceed an increase of more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours.

Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic acute hyponatremia 2,4

- Where possible, discontinue use of medications that can worsen hyponatremia

- Treat underlying condition, if known

- If the sodium concentration has fallen by more than 10 mmol/L from normal, may consider IV bolus 150 ml 3% hypertonic over 20 min

- Check serum sodium at the 4 hour mark

- Do not exceed an increase of more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours.

Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic chronic (or “compensated”) hyponatremia 1,2

- Where possible, discontinue fluids or medications that can worsen hyponatremia.

- Treat underlying condition, if possible.

- Check serum sodium every 6 hours.

Overrapid correction4

- Often caused by water diuresis after resolution of underlying cause of hyponatremia

- Discontinue treatment if sodium has increased by more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours

- Call for a consult

- Monitor serum sodium every 2 hours until correction, then every 4-6 hours for the next 48 hours.

Additional guidelines have been developed for patients with expanded ECF, SIADH, and reduced circulating volume.2,4

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Case review

Marjorie’s history indicates that she is likely suffering from chronic, moderately symptomatic, severe euvolemic hyponatremia, likely secondary to the use of a thiazide diuretic. Because of the short half-life of hydrochlorothiazide, her sodium is expected to start correcting itself within 24 hours of stopping this drug together with fluid restriction. Her hyponatremia is severe but only moderately symptomatic, so overzealous acute correction should be avoided. She is given a single 150 mL bolus of 3% hypertonic saline, raising her serum sodium to 112 mmol/L, and referred to medicine for admission.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Conclusion

That’s hyponatremia in a nutshell. As always, clinical guidelines and emerg fanatic websites are not a substitute for clinical analysis and decision making. There is some disagreement even among experts and it is always best to tailor therapeutic strategies to each individual patient.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Appendix 1 – Calculating infusion rates

I have found calculating infusion rates challenging. I will try to explain it here as simply as I can.

To calculate an infusion rate, you need:

- Your patient’s weight in kilograms (let’s say our patient weighs 100kg)

- An estimate of your patient’s body water, usually derived by multiplying their weight by a fixed factor (0.6 in adult males and children, 0.5 in elderly males and females, and 0.45 in elderly females) (let’s say our patient is an adult, non-elderly female, so we use 0.5)

- Your goal for how much you would like to raise sodium concentration by, and over what period of time. Let’s say 6 mmol/L over the next 12 hours, or 0.5 mmol/L/hr.

- The fluid you would like to use. Let’s say normal 0.9% saline, which contains 154 mmol of sodium/Litre, as well as the patient’s current sodium level.

The formula:

- Weight x Correction factor +1 = (100*0.5)+1= 51L Estimated Total Body Water (ETBW)

- Targeted hourly increase in sodium concentration x ETBW =0.5mmol/L/h * 51L = 25.5mmol/h

- 25.5mmol/h / (154mmol/L – 110mmol/L) = 0.580L/h = 580mL/h

This article was copy-edited by Kevin Lam (@KevinHLam). This post was edited on March 27, 2018 to correct a calculation in Appendix 1. Thank you to Bee Key for spotting the error.

References

Reviewing with the staff

Hyponatremia in the emergency room. There are two types of hyponatremic patients: those that are dying and those that are just waiting to die. For the latter, please order the initial work-up, put away your normal saline, and wait for the medical team to see and admit the patient. For the patients that are seizing, not breathing, vomiting, or in a coma it is go time. These patients cannot wait for an ICU evaluation or the admitting resident to mosey down to the ED. They need immediate osmotic relief in the form of 3% saline.

I am a fan of the European hyponatremia recommendations outlined in the blog post. They are simple to understand; they dispense with the need for calculations and gets patients the therapy they need quickly. The guidelines call for 300 ml of 3% over 40 minutes and with a sodium check half way through. But understand, though you are supposed to draw the sodium after the first 150 mL, you are not supposed to slow or stop the infusion. It is just done so that you will have an idea how fast the sodium is going to correct with the 3%. For average size patients 100 mL of 3% will raise the sodium about 1 mmol/L so this will get you only a little way, so do not be surprised if you need to continue with the hypertonic saline boluses to stop the acute symptoms.

One important note about the case of Marjorie. We have little information besides the fact that she is on thiazide diuretics, and has concurrent hypokalemia. Let’s suppose this is thiazide induced hyponatremia. The cause of the hyponatremia is release of ADH in response to the decreased perfusion from the thiazide-induced volume depletion. 3% saline is an excellent resuscitation fluid because it not only delivers volume from the infusate (80 cc/hr in this example) the high osmolality will pull fluid from the intracellular compartment further increasing the intravascular volume. As soon as the volume is restored the hypothalamus will shut down ADH and the patient will start pouring out copious amounts of maximally dilute urine. This will cause the serum sodium to rush upwards and could cause osmotic demyelination syndrome. Doctors using 3% (or saline) in these cases need to be aware of this and be ready to slow the rise in serum sodium with D5W and/or DDAVP (pharmaceutical ADH).