The Canadian CT Head rule is a great rule. Really. Yet, time and time again we see it applied erroneously, or learners fail to appreciate the population for whom this decision rule was meant. Patients with head injury are often seriously over investigated, and this likely is secondary to a lack of appreciation regarding decision making. Here, we seek to dissect some of the nuances.

The vast majority of literature examining the utilization of imaging in patients with head injury is focused on patients with minor head injury1.

Minor head injury is defined as a loss of consciousness, definite amnesia or witnessed disorientation in patients with a GCS 13-15.

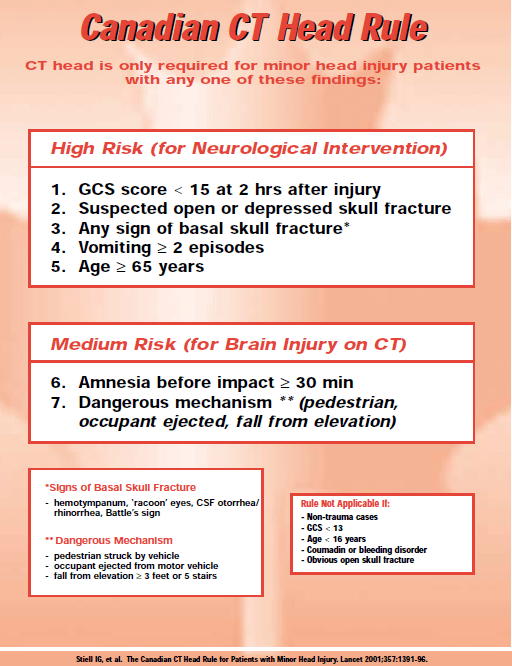

In all cases of head trauma, it is the role of the ED physician to rule out intracranial pathology. Fortunately, the Canadian CT Head Rules (CCHR) helps to provide further clarification on who requires neuroimaging in patients with minor head injury1. Notably, the vast majority of patients presenting to the ED do not meet the inclusion criteria for minor head injury, but rather, have suffered a minimal head injury.

If we were to examine an isolated case, presume a 25 year old male football player had a hit to the head, and was knocked unconscious, and then presented to your Emergency Department, GCS 15 and neurologically intact. It would not be a stretch to assume that a number of physicians would perform an CT scan of this patients head, under the ‘gestalt’ that an loss of consciousness is concerning, however, this component to the history only puts us in the minor head injury category and allows us to actually apply the CCHR.

Canadian CT Head Rule

The CCHR has a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 68.7% to identify patients requiring neurosurgical intervention following minor head injury. While it was anticipated that neuroimaging would decrease following implementation, a multicentre prospective implementation study found that imaging actually increased from 63-68% to 74-76%, despite adequate promotion and education of the decision aid2.

So what gives? Why so many more scans, despite a decision rule providing us with the utility to decrease imaging? A number of studies have evaluated this, but physician practice habits are difficult to study, however, it appears that the CCHR are being erroneously applied to patients with minimal head injury, or that features from the CCHR are being inappropriately incorporated into physician “gestalt”. Dr. Ian Stiell also recently discussed this on an edition of Canadian EMRAP.

There are no decision rules to help us with what to do with minimal head injury patients. Fortunately, the vast majority of these patients are unlikely to have pathology, so it is important to determine which high risk patients do require further investigation.

Minimal Head Injury

One of the largest studies on patients with minimal head injury was a prospective cohort study on over 1100 patients following head injury, and they found that3:

- Without any risk factors present

- 1.8% had an intracranial finding

- 0.4% required neurosurgical intervention

- With risk factors present*:

- 5% had an intracranial finding

- 0% required neurosurgical intervention

*Risk factors 4:

- Persistent nausea and vomiting

- Suspected child/elder abuse

- Seizure

- Palpable depressed skull fracture

- Anticoagulation or bleeding diasthasis

- Age <2 or >65 WITH a severe headache, nausea/vomiting

- Extracranial injuries that alone require admission

The authors ultimately concluded that a minority of patients with minimal head injury will have pathology, and that there is clearly a need for guidelines to help minimize the over-utilization of imaging in these patients.

Scandinavian Guidelines

Since then, only guidelines created to help us in the management of the patient with minimal head injury come from the working group that created the Scandinavian Guidelines5,6. A robust systematic review led the working group to recommend:

“that adult patients after minimal and mild head injury with GCS 15 and without risk factors (loss of consciousness, repeated (≥2) vomiting, anticoagulation therapy or coagulation disorders, post- traumatic seizures, clinical signs of depressed or basal skull fracture, focal neurological deficits) can be discharged from the hospital without a CT scan (moderate quality, strong recommendation).” 5

These guidelines have subsequently undergone a validation study at 6 ED’s in New York/Pennsylvania in the form of a retrospective nested cohort study, and found that in 662 patients presenting with head injury, 93 met their inclusion criteria for minimal head injury without risk factors and 0% of patients had findings on CT head6.

Bottom Line:

Ultimately, it appears that patients without significant neurological risk factors and minimal head injury are unlikely to have significant pathology, so do not likely require neuroimaging. However, the more important point is to remember not to erroneously apply the Canadian CT Head Rule to these patients. The individual who falls down and hits their head, but doesn’t lose consciousness, is fully alert/with a normal neurological exam, and no other complaints is unlikely to have significant pathology. To help develop a more conservative imaging strategy, the utilization of these high-risk features may help you determine who ultimately requires further imaging.

Furthermore, to help educate physicians further, the utilization of integrated clinical support tools can help to ensure these rules are being applied appropriately. A recent study demonstrated decreased inappropriate CT ordering and enhanced diagnostic yield for patients with minor head injury when employing physician education and integrated decision-making tools (i.e.: on electronic medical records or online test ordering)7.

What if the patient is anticoagulated?

In the majority of studies looking at head injury, patients are typically excluded if they are anticoagulated or have a bleeding diathesis, so when they come in with a minor head injury these patients can present a diagnostic dilemma. In one historical cohort study over two years, patients were included if they had minor or minimal head injury in the setting of anticoagulation use with a primary outcome of intracranial bleeding. They excluded any patients with an INR < 1.5, penetrating injuries or with a focal neurological deficit8.

Of 176 patients enrolled, 89.2% had a CT head, and of these 15.9% had an intracranial bleed.

- 21.9% of the minor head injury group had intracranial bleeding

- 4.8% of the minimal head injury group had a rate of bleeding

This evidence suggests that anticoagulated patients, even with minimal head trauma, can have significant morbidity and mortality, and correlates well to existing literature on the topic [9,10]. We should maintain a low threshold for neuroimaging in these patients. It should also be noted that patients on Plavix also have an elevated bleeding risk, and we should maintain caution around these patients with head injury9. A recent publication suggested that patients with ground level falls on ASA have increased rates of intracranial hemorrhage10, however, this study had a litany of design falls, that make it difficult to ascertain the true effect of ASA in head injury. While controversial, the jury is still on the risk of clinically relevant intracranial events in patients on ASA.

[bg_faq_start]