Mark is a 7-year old boy who was brought into the ED by his mom who noticed he has been more fatigued than usual over the past day. Three days ago, he had rhinorrhea and a cough, and since then has been complaining of generalized abdominal pain, nausea, 2 episodes of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis today, and increased thirst. He is otherwise healthy, takes no medications, has no allergies, has up to date immunizations and has not travelled recently. Other family members including parents and a 4-year old sister are healthy without symptoms. Mark’s initial vital signs are T-37.2, BP 90/60, HR 140, RR 30, SpO2 98% RA, cap refill 2 seconds, with dry appearing mucous membranes. His weight is 30kg. He is able to answer your questions, but appears quite fatigued, lying supine on the examination stretcher.

What are your next steps?

The child in this stem appears unwell, so it is appropriate that you are concerned. Mark’s systolic BP is around the borderline minimum value for his age (a quick way of calculating minimum SBP = > 70 + (age x 2), which would be 84 in this case), he is tachycardic and appears dehydrated. Mark should be placed in a monitored bed with adequate nursing support, and 2 lines for IV/IO access should be established. A cap glucose should be taken for any child who appears to have features of DKA or altered level of consciousness. A thorough assessment of the ABC’s should be performed, and continuous cardiac and O2 monitoring with frequent reassessment of his vital signs and neurological status is important. Bloodwork containing a CBC, lytes, BUN, Cr, ext lytes, VBG, HbA1c, serum bHB/ketones and urinalysis for ketones should be expedited1. In cases such as this, consider other targeted investigations if there are any indications of infection (blood, urine, throat), ECG for baseline assessment of K+ status if the serum K+ is delayed)

[bg_faq_start]Mark’s bedside cap blood sugar is 35. Now what?

The diagnosis in this case is DKA. All cases of Pediatric DKA should be managed very carefully according to a pediatric specific DKA protocol at your center. Pediatrics consultants should be notified of the patient once management is underway for disposition planning. [bg_faq_end]

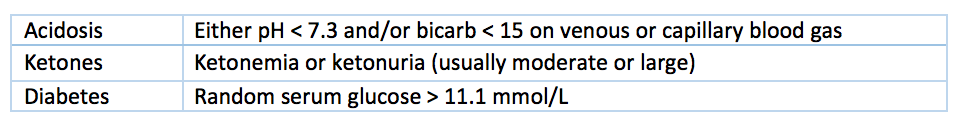

The diagnostic criteria for DKA

To establish the official biochemical diagnosis of DKA, the 3 following diagnostic criteria must be met2:

What are the general principles behind pediatric DKA management?

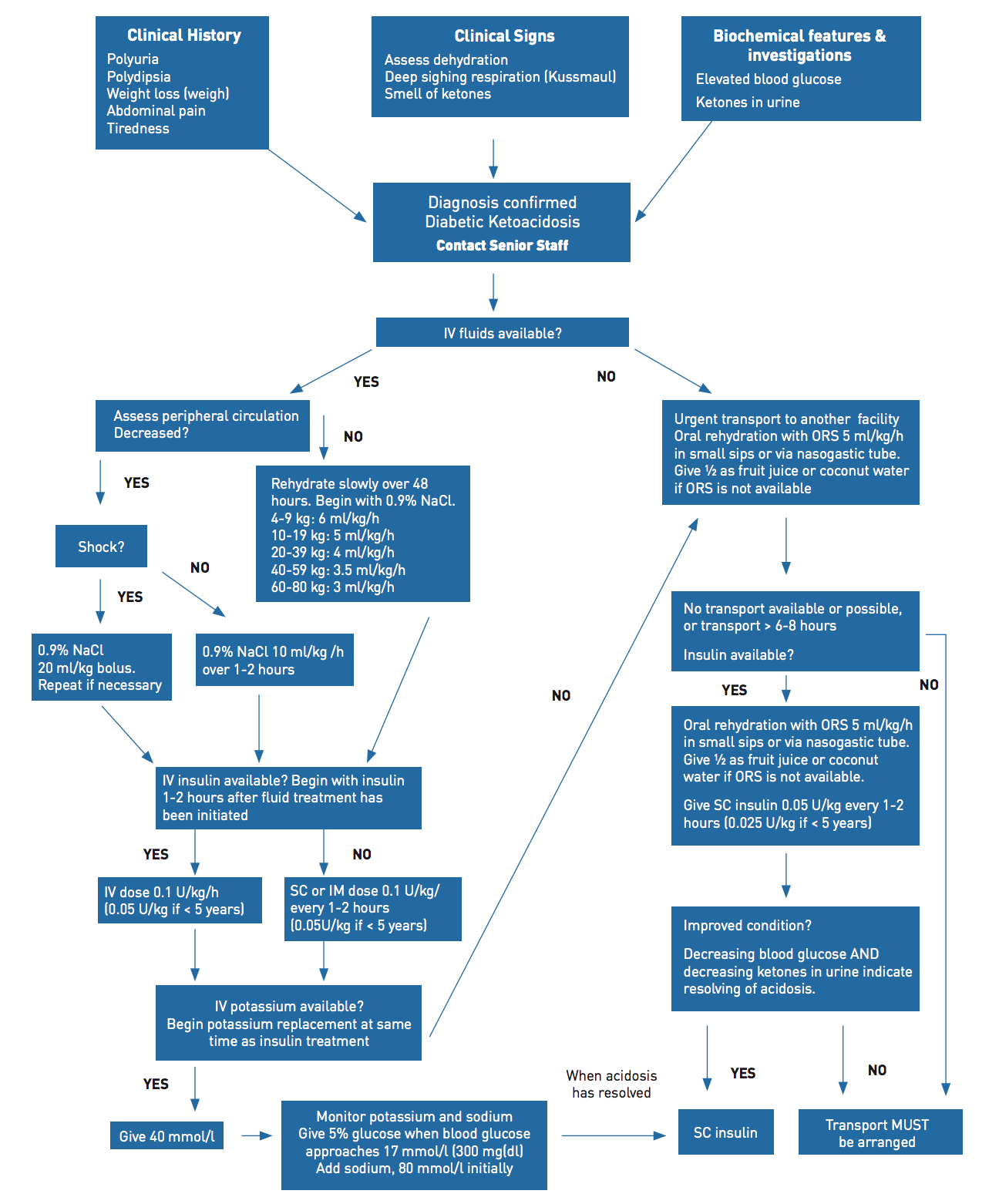

Fluid therapy

0.9% NaCl IV boluses should only be used to treat shock (hypotensive, delayed cap refill >2 s) and cardiovascular compromise. In general, each bolus should not exceed 10 mL/kg. In the majority of kids who are not in shock, fluid deficits should be replaced evenly over 48 hours, and the infusion rate should not ever exceed double the maintenance rate. See the algorithm below for weight-based infusion rates. Initial fluid choice should be 0.9% NaCl with as per hospital protocol. Potassium should be added to maintenance fluids only once the patient is voiding and serum K is <=5 mmol/L. The fluids should be changed to D5W+NS once the blood glucose drops below 15, or decreases by >5 mmol/L/hour. Ins & outs should be monitored stringently.

[bg_faq_start]The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) & International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) have an easy to use flow-chart for fluid calculation.

IV insulin infusion

Insulin should never be given as an IV bolus in pediatrics- as it leads to increased risk for cerebral edema1–4. Insulin infusion should be started 1-2 hours after IV fluid has been initiated due to an association of early insulin infusion with cerebral edema3. Usually the infusion rate is between 0.05-0.1U/kg/hour of regular insulin (R)1. The goal of the insulin infusion is to close the anion gap, not to normalize the blood glucose level.

Electrolyte monitoring

The electrolytes (most importantly K), VBG and glucose level should be regularly monitored. The glucose should be checked hourly, while the electrolytes and VBG should be checked every two hours. To correct for Na in hyperglycemia, an easy calculation is for each 10mmol/L the glucose is above 8, add 3 to the serum Na. The other way is, corrected Na = measured Na + 2(plasma glucose – 5.6)/5.6 2

Consultation with a pediatric specialist or PICU

If the patient presents to a peripheral hospital or a hospital that does not admit pediatric patients, transfer should be arranged with a critical care paramedic team. Alternatively, they can be transported with a healthcare professional who can manage an insulin infusion and any worsening in the patient’s condition.

*Of note, bicarb should not be administered to pediatric patients with DKA as this can increase the risk of cerebral edema2.

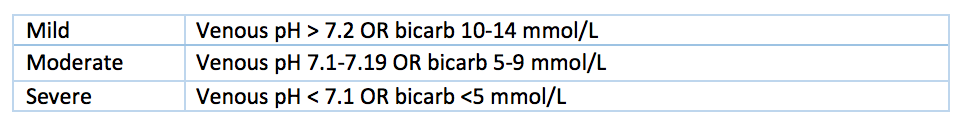

Mild, Moderate, and Severe DKA

Typically, these are organized in relation to the degree of acidosis on a VBG4:

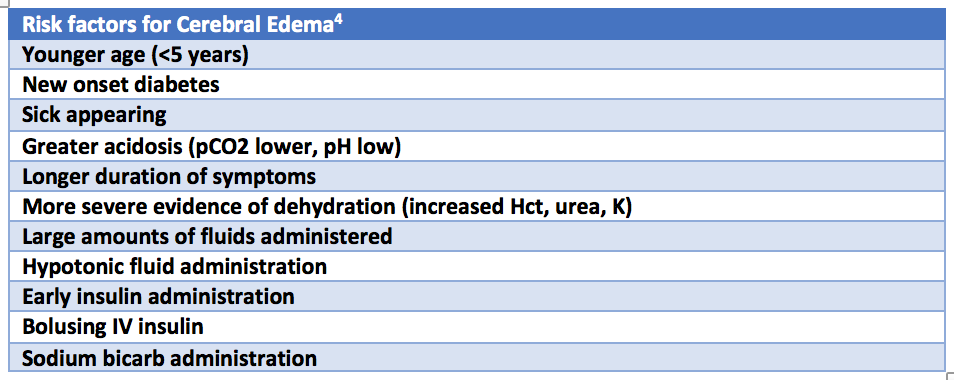

Cerebral Edema and DKA

Cerebral edema is almost exclusively a pediatric phenomenon, complicates up to 1.5% of DKA episodes, and is linked with morbidity and mortality4. Cerebral edema refers to the accumulation of water in the brain parenchyma. Risk factors for cerebral edema are both patient and treatment related4.

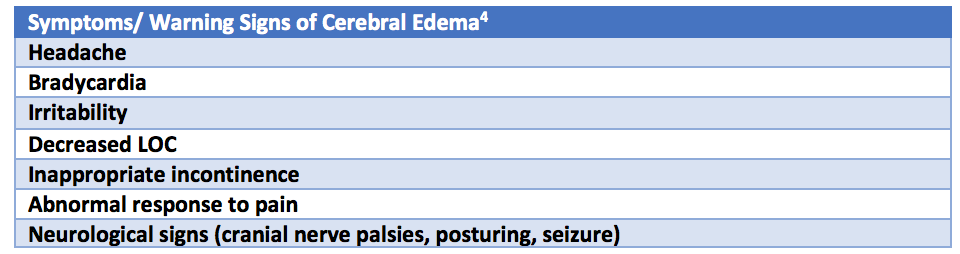

The symptoms/ warning signs of impending cerebral edema are listed below. Ensure you check the blood glucose if any of these symptoms arise as they could also be related to hypoglycemia.

If cerebral edema is suspected, the management of ABC’s, restriction of IV fluids to maintenance, elevation of the head of the bed, Mannitol at 0.5-1g/kg IV over 20 mins, and/or 3% NaCl (5-10 cc/kg IV over 30 mins) is recommended4. Intubation is rarely required and is a high risk procedure in DKA patients, as rising CO2 can lead to arrest, so be cautious, and do so in consultation with PICU/ Provincial transport service. The most experienced operator should establish a definitive airway if needed, and the patient would need to ventilated at pre-intubation RR (EtCO2 of 30-35) as a temporizing measure for increased ICP. A brief period of hyperventilation may be considered in the setting of acute herniation. Once the patient is stabilized, a head CT should be performed at a pediatric centre.

[bg_faq_start]The overlap between hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS) and DKA

Typically, HHS may occur in young patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, but it is also rarely possible in type 1 diabetes patients. It is more likely in obese individuals who have type 2 diabetes. HHS can also occur in type 1 diabetes when the patient has been drinking high-glucose drinks. Children can have a mixed picture of both DKA and HHS.

The criteria for HHS include2:

- plasma glucose > 33.3

- arterial pH < 7.3

- serum bicarb > 15 mmol/L

- small ketonuria, absent to mild ketonemia

- serum osmolality > 320 mOsm/kg

- stupor or coma

It is important to know that fluid losses in these patients usually greatly exceed those of patients in DKA. These patients should be managed along the same principles as those with DKA.

[bg_faq_end]What now?

Almost all new cases of DKA get admitted to hospital for IV fluids, insulin, and monitoring. Rarely In some older children with mild DKA requiring only subcutaneous insulin, resolution of acidosis, and close follow-up with pediatric endocrinologist, there is a possibility of discharge from ED3,4. Cases of severe DKA, cerebral edema, and children < 5 years of age should have strong consideration for admission for close observation4.

Back to the Case

In this case, Mark was immediately placed in a pediatric monitored bed and 2 large bore IV’s were established. The Pediatric DKA order set protocol was followed, with continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring. Initial labs drawn included a CBC, HbA1c, lytes, glucose, Cr, urea, VBG, urine ketones and urine glucose, and then repeat lytes, glucose, Cr, urea every 1-2 hours.

Initial labs showed a glucose of 32, pH of 7.05, PaCO2 20, Na 133, K+ 4.5, Cl 96, CO2 5, urine showed 4+ glucose and large ketones. This categorized Mark into that of severe DKA.

Mark was given 4cc/kg/hour (x 30kg) = 120 cc/hour over 48 hours. 40 mmol/L of KCl was added to the maintenance fluids. A continuous insulin R infusion of 3U/h (0.1U/kg/h x 30 kg) was started after the initial 0.9% NS IV fluid bolus had ran through the IV. The Pediatrics consultants admitted Mark to the hospital. He was discharged 2 days later after being started on subcutaneous insulin by the Pediatric Endocrinology team who will be following Mark as an outpatient.5

References

Reviewing with the Staff

This case highlights the important issues related to DKA in pediatric patients. While rare, cerebral edema is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients and thus emergency physicians must remain vigilant for signs of this complication. Remembering to perform a blood glucose in any sick child, those with the classic history of polyuria/polydipsia/weight loss and/or those with tachypnea NYD will help identify diabetes and DKA in the ED.

Following a pediatric DKA protocol will ensure you are providing the standard of care for these patients. The slow repair of metabolic derangements over 48 hours is the mainstay of DKA treatment. IV fluid (0.9% NS to start) is given to replace moderate dehydration + maintenance. IV fluid is reduced to maintenance in the setting of cerebral edema. Insulin infusion is started 1-2 hours after IV fluid is started. Elevation of the head of the bed and the use of 3% NS and/or Mannitol is added to the treatment of those with cerebral edema. Vital signs, neurologic status and blood work are monitored closely. In the extremely rare situation of a DKA patient with decompensated shock, bolus fluid would be given until BP/perfusion is normalized. Airway management would be considered in a DKA patient with severely impaired level of consciousness or impending herniation but should only be undertaken with consultation given the high risk nature of this procedure.

Most children with DKA do very well and are discharged from hospital within about 48 hours. As emergency physicians, our job is to identify diabetes and DKA, assess patients for signs of cerebral edema and treat these children according to a pediatric-specific published protocol.