You are getting handover at the beginning of a shift in the emergency department (ED) and hear about a 71 year old woman who presented with a hip fracture. You’ve read about the benefits of nerve blocks for hip fractures, but still don’t feel prepared or supported to perform one. You text message a couple of colleagues and realize you are not alone. Others also understand that there are clear benefits, but don’t feel prepared to perform this skill. You think: it’s time to start a quality improvement (QI) project to improve access to fascia iliaca nerve blocks for patients with hip fractures in your ED. But how can you measure the current state in your ED and whether you’ll be making progress?

Welcome to another HiQuiPs post, where we will explore the different types of measures that can be used in a QI project!

Where does measurement fit within the organizational change process?

Measurement is a critical element of improvement. Without measurement, improvement is invisible. But there is also no limit to how complex measurement can be (think of research studies). For these reasons, getting the right measurement plan for your project is critical.

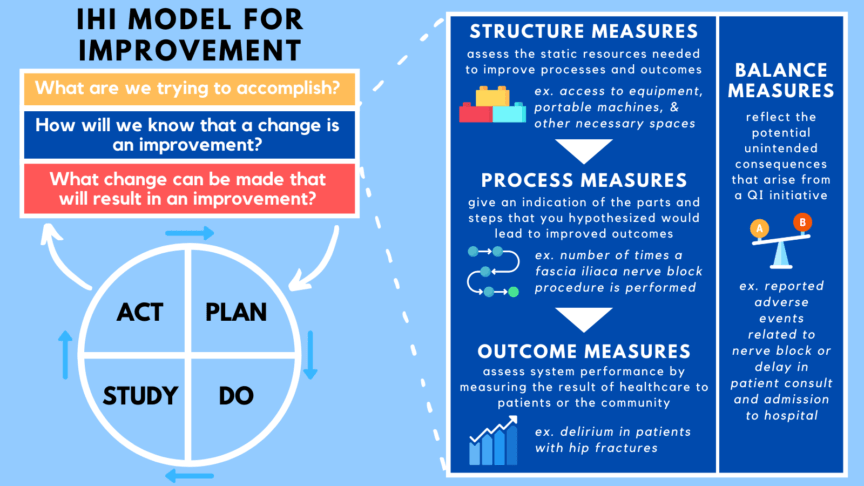

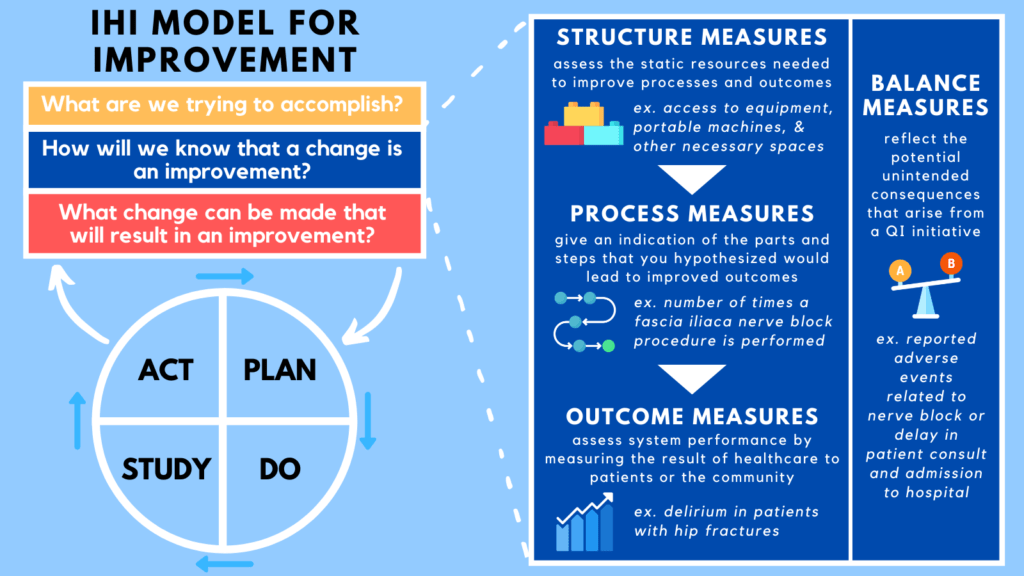

As we’ve seen in previous posts, there are many models for QI work. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s model for improvement (MFI)1 has been created specifically for QI in the health care setting. Figure 1 demonstrates the MFI and the measures that contribute to it which are discussed in this article.

The model consists of three questions to set your project on the right track, along with the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle which provides a way to move your project forward. You can learn more about this model in this previous CanadiEM post. The second question of the MFI, “How will we know that a change is an improvement?” asks you to choose the measures used in the project. Measurement enables a team to identify results and adapt interventions in order to accomplish organization-specific goals effectively.

What types of measures should I use in my QI project?

Previously we discussed Donabedian’s framework for healthcare quality that includes a model of structure, process, and outcome measures. In this post we further explore these concepts.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures were originally defined as measures related to, “recovery, restoration of function and of survival”2. Now, outcome measures have a more broad definition of system performance, and ask questions including, “How does the system impact patients’ health and wellbeing?”.3 In short, this is the end result of the intervention to patients or the community. Outcome measures are limited, however, as there is a time lag before relevant outcomes manifest and there are many factors outside of a project or even the healthcare system that affect patient outcomes (e.g. quality of life)2. The more meaningful the outcome (e.g. improving quality of life), the more multifactorial the causation, the harder to measure, and the more lag you can expect between cause and effect.

For this reason, it is important to bring the concept of outcome measures to a level more amenable to QI. These indicate events or states that precede survival or functional outcomes, but have a good basis of evidence supporting their link to patient-centred outcomes. You could think of them as intermediate outcomes. For instance, using an evidence-based therapy may be a suitable outcome in the setting of a QI intervention as long as prior evidence is strong. In your QI project on fascia iliaca nerve blocks, outcome measures may include a patient-reported pain scale, or amount of opioid use for pain control.4

Process Measures

Process measures were originally defined as components of care delivered, where judgments are based on considerations such as appropriateness and justification of diagnosis and management, among other factors.2 In the context of QI, process measures are the parts and steps that you hypothesized would lead to improved outcomes. Process measures are indicators of the specific ways through which outcomes are changing. Process measures for your project may include the percentage of hip fractures receiving nerve blocks in your ED, or time to initiation of a hip block after hip fracture identification.4

Structure Measures

Donabedian’s final measure was structure measures which are used to assess the static resources needed to improve processes and outcomes.2 For instance, equipment availability, accreditation of hospital facilities and staff are all static and structure measures. In QI, these features are usually assumed and static and not part of ongoing measurement. In your QI project, a structural measure would be access to hip block related equipment, portable machines, and other necessary spaces. If these are modifiable during the duration of the project, they are usually considered process measures.

Balancing Measures

“Every action has an equal and opposite reaction.” Newton’s third law of motion is the basis of the fourth measure that is outside of Donabedian’s Framework: balancing measures. These reflect the potential unintended consequences that arise from a QI initiative. They answer the question: “are changes designed to improve one part of the system causing new problems in other parts of the system?”3 In your QI project, the balancing measures could be reported adverse events related to nerve block (such as local anesthetic toxicity, infection, or nerve damage), delay in patient consultation, or admission to hospital.

Each type of measure is important, and it is crucial to set them up from the onset of the project and have a plan for accessing this information. What you wish you could measure and what can be measured are rarely the same, here is how you may tackle your project.

Case resolution

After carefully considering the types of measures you could include in your QI project, you decide to use 2 measures. The first is the process measure of the percent of hip fractures receiving nerve blocks in your ED. The second is the outcome measure of a patient-reported pain scale for patients that present to the ED with a hip fracture. You chose these measures because both of them can be easily measured in your ED, and ultimately, can contribute to identifying the optimal way to provide care for patients presenting with hip fractures.

Conclusion

QI projects and research projects require the same rigour and logic, but a different level of complexity. It is important to develop a clear plan for measurement, analysis, and reporting at the outset of a QI project. Measurement will be your guide to understand what works and doesn’t throughout your project. Join us in the 2nd part of this post where we will discuss other practical tips with QI measurements.

Senior Editors: Dr. Shawn Mondoux (@DrShawnMondoux), and Dr. Ahmed Taher (@ak_taher)

This post was copyedited by Camilla Parpia (@camillaparpia)

**UPDATE (November 2020): The HiQuiPs Team is looking for your feedback! Please take 1 minute to answer these three questions – we appreciate the support!**

- 1.How to Improve. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Accessed November 8, 2020. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx

- 2.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691-729. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x

- 3.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Science of Improvement: Establishing Measures. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Accessed November 24, 2020. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementEstablishingMeasures.aspx

- 4.Watson P, Rugonfalvi-Kiss S. Improving analgesia in fractured neck of femur with a standardised fascia iliaca block protocol. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1). doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u202788.w1370