A 55 year-old primarily Punjabi-speaking man presents to the Emergency Department (ED) and describes a three day history of fever, cough, with five days of myalgia and general fatigue. He is not in acute distress, his vital signs are within normal limits, and he does not meet testing criteria for COVID-19. You suspect he could have COVID-19, and he is worried about infecting his wife. Your priority is to give him advice he can understand and apply on how to self-isolate and care for himself.

Communicating information to patients at discharge is critical to outcomes, and the COVID-19 pandemic has made this clearer than ever. Since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, a large number of patients with symptoms concerning for COVID-19 started presenting to EDs, with no capacity to test them. Many patient assessments are rapidly performed in assessment zones, with a limited opportunity to discuss self-management or usual discharge instructions.

We developed easy to understand, visual instructions that can be printed in black and white on a single one-sided standard page to support people in caring for themselves at home and through self-isolation.

[bg_faq_start]Methods

A group of clinicians and the Health Design Studio at OCAD University had been collaborating on redesigning the discharge process after ED care when the pandemic was declared. They temporarily redeployed their work toward developing easy to understand educational material for patients, intended to be given at ED discharge.

Based on the clinical experiences of the team’s ED physicians and survey of other frontline clinicians, an initial need was identified to support patients on 1) how to care for COVID-19 at home and 2) how to self-isolate.

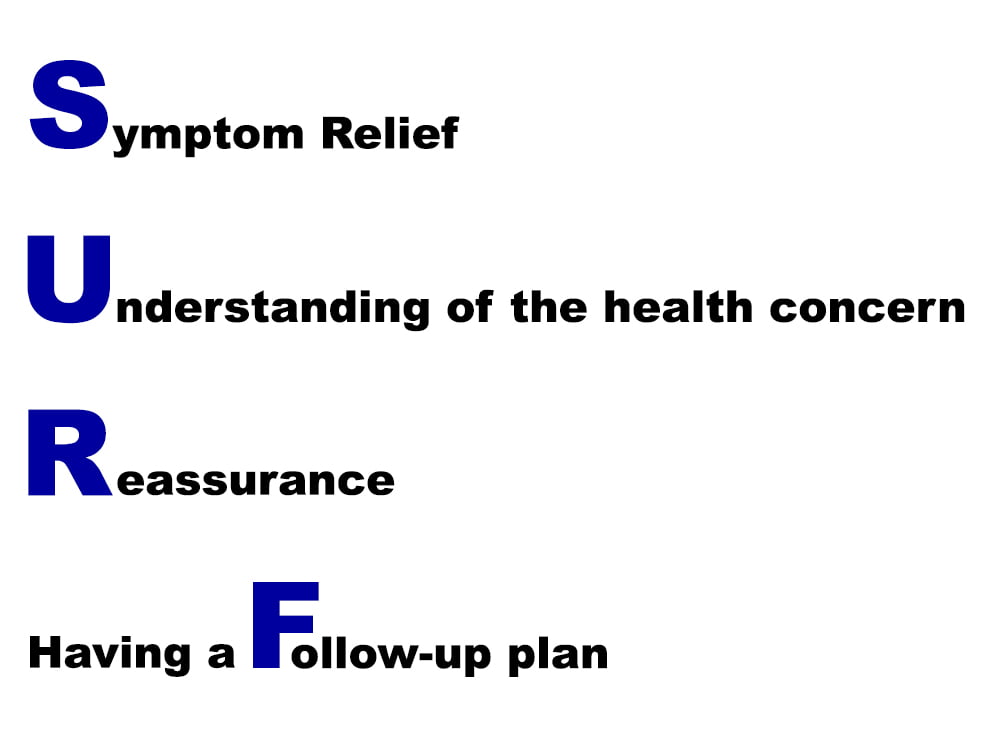

Our work was informed by the previously developed SURF framework on patient outcomes after ED care1:

We used a rapid iterative design method, using principles of inclusive design to develop the documents2. This design was also informed by prior research on designing effective communication materials for patients/family caregivers3,4. We focused on using visual language, including infographics, simple layout, and a plain language style. The content was informed by guidelines from Toronto Public Health, Ontario Public Health, and the Public Health Agency of Canada. We subsequently reviewed how information was conveyed in different provinces, certain American states, and the United Kingdom.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]Results

The initial versions of the first two documents were posted to our website on March 19, 2020 (six days after project conception). We used an open innovation approach to facilitate the rapid sharing and spread of the materials5. They were originally added to the website in a PDF format. We quickly learned from initial feedback that the end-user clinicians using these documents wanted to be able to customize them for their local institutions. We, therefore, made the decision to change to Google Document versions. We highlighted specific sections of the documents to encourage local modification and branding, spread, and sharing.

We identified the need for documents to be translated to make them more accessible. Translations in five languages were released on March 20 by members of the team, family, and friends. One of the team members coordinated an open call to University of Toronto medical students, bringing the total number of languages to 26 by March 23.

As there were rapid changes to Public Health guidelines and feedback was given to improve language, the documents, in all languages, went through three rounds of updates. Over time, the translation services took on a grassroots spread. Individuals from across Toronto, from different provinces, and from the Czech Republic reached out to team members directly or through our website volunteering to translate or requesting that the documents be translated into more languages. With the help of medical students, their family/friends, and different community organizations, the total was brought to 43 languages.

Finally, at the beginning of April, our team collaborated with Access Alliance, a Community Health Centre in Toronto, who provided professional translation of our documents. The documents are now available in 45 languages, with 39 languages having been professionally translated, and can all be found on our website as Google Docs, shared under Creative Commons license5.

The documents, in English and French, can also be found here:

ENGLISH – COVID-19 Self-Management Sheet

FRENCH – COVID-19 Self-Management Sheet

ENGLISH – COVID-19 Self-Isolation Sheet

FRENCH – COVID-19 Self-Isolation Sheet

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]Conclusion

These one-page printable documents have been recognized as recommended resources by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) and the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and have been used across Canada and in other countries, including the United States, Ecuador, Australia, Latvia, and the Czech Republic. Originally intended for ED discharge, they have been used by groups in community settings as well, including Community Health Centres, agencies aiding refugees, and family physicians.

Our makeshift efforts that started with a small team now includes a working group made up of 20 members from design, medical, and public health backgrounds. We have been approached with requests for infographics on: eligibility for COVID-19 testing; social distancing in apartment/condominium buildings; the differences between social distancing, self-isolation, and isolation; and hospital visitation. These documents have/are being professionally translated into a number of languages.

The team continues to monitor Public Health guidelines and is developing strategies to more robustly evaluate the use and impact of the infographics. An initial need for a discharge information tool has now become a way for us to improve health communication using simple, editable, and shareable documents. We hope that you can use, edit, and adapt to your needs!

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]Additional Team Members

Christopher Rice, Victoria Weng, Yesmeen Ghader, Habiba Soliman, Christina Dery, Joanna Rios, OCAD University; Galo Ginocchio, Unity Health Toronto; Dr. Jaspreet Khangura, Alberta Health Services.

[bg_faq_end]This post was copyedited and uploaded by Maham Khalid.

References

- 1.Vaillancourt S, Seaton M, Schull M, et al. Patients’ Perspectives on Outcomes of Care After Discharge From the Emergency Department: A Qualitative Study. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(5):648-658.e2. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.05.034

- 2.Clarkson J, Coleman R, Keates S, Lebbon C. Inclusive Design: Design for the Whole Population. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013.

- 3.Borba MR, Waechter HN, Borba VR. Contributions of Graphic Design for Effective Communication in the Health Campaigns. In: Proceedings of the 7th Information Design International Conference. Editora Edgard Blücher; 2015. doi:10.5151/designpro-cidi2015-cidi_86

- 4.Waisman Y, Siegal N, Siegal G, Amir L, Cohen H, Mimouni M. Role of diagnosis-specific information sheets in parents’ understanding of emergency department discharge instructions. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12(4):159-162. doi:10.1097/00063110-200508000-00003

- 5.Avital M. The generative bedrock of open design. In: Open Design Now: Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers; 2011:48-58.