Think back to your last three shifts. Did you see an alcohol related condition? You might even notice a pattern— the same patient, the “regular” who returns time and time again with the same presentation. You may even find yourself writing “discharge home when ambulatory” as you’ve “reached your wits end” and don’t know what to do anymore.

The use of alcohol is common and the emergency department is often where we see many of alcohol’s complications. Interestingly, despite alcohol’s massive impact and frequency, anti-craving medications for alcohol which are safe and effective are notoriously underprescribed and alcohol use disorder frequently goes untreated.

The emergency department may be a novel setting to intervene in alcohol use disorders.

Why Is Alcohol An Issue?

15% of the Canadian population would be consider at risk drinkers (consume alcohol in excess of the recommended low risk drinking guidelines).

At Risk Drinking versus Alcohol Use Disorders

Its important to recognize the spectrum of alcohol use.

At Risk Drinking:

- Drinks above recommended guidelines

- Men: 0-3 standard drinks/day with no more than 15 per week

- Women: 0-2 standard drinks/day with no more than 10 per week

- Does not meet criteria for alcohol use disorder

– At Risk Drinkers are frequently responsive to brief advice and motivational interviewing alone,

Alcohol Use Disorder:

- Characterized by a constellation of withdrawal symptoms, tolerance, time which is spent either recovering from alcohol, obtaining alcohol or using alcohol and social/functional impairment secondary to alcohol.

- Alcohol use disorder (AUD) requires pharmacotherapy, abstinence and formal treatment programs.1

How to identify Alcohol Use Disorders

History:

Use a validated tool such as:

- Sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 90% for identifying lifetime alcohol problems.

2. Binge Drinking Question:

“How many times in the past year have you had five or more drinks (four or more if a woman) on one occasion?”

- Sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 65% but only in a primary care population 1

Laboratory Manifestations of Heavy Drinking:

The two most reliable serum markers are:

- Gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT)

Frequently elevated in alcohol use disorders. Importantly, GGT does not necessarily indicate alcoholic hepatitis. GGT is frequently elevated because alcohol results directly in enzyme induction.

Utility:

- Corroborates a suspicion of heavy drinking (translated to >4 standard drinks per day)

- Reliably declines with abstinence with a half life of 2-4 weeks.

- Mean Cell Volume (MCV)

Alcohol directly impacts the maturation of red blood cells resulting in a slightly larger red blood cell.

Importantly, as individual measurements neither GGT or MCV are highly sensitive but together they can be important markers suggestive of a possible alcohol use disorder.1

Interventions

Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT)

It takes 5 minutes! Applying an SBIRT strategy has been shown to result in clinically significant decrease in the quantity of alcohol consumed at 6 weeks to 12 months (independent on pharmacotherapy).2,3

The approach:

- Ask for permission to talk about substance use and overdose.

- Screen for other substance use

- Screen for safety (suicidal ideation)

- Review low-risk drinking guidelines (the patient may be surprised to know how their drinking compares to the Canadian average)

- Link the patient’s drinking with their current health, mood, sleep and functional impacts of alcohol

- Express concern about drinking patterns.

- Ask about the connection to ED visit. “How do you think your alcohol use is connected to your visit to the emergency department today?”

- Enhance Motivation

- Ask the patient to identify readiness for change on a ruler/scale. “On a scale of 1 to 10 how ready are you to make a change today?”

- Ask why the patient chose this number and not a lower one (allows them to identify positive factors encouraging change)If the patient chooses 1 on the readiness ruler ask “what would make this a problem for you?”

- “Where do you want to go from here?”

- “What would make tomorrow better than today?”

- Develop a discrepancy between current behaviours and their goals.

- Negotiate and Advice

- Discuss what the patient would like to do (ex. reduce drinking to 3 drinks on Thursdays). Include in this plan an opportunity to connect to a treatment resource in the community. Treatment might include addictions counseling, a rapid access addictions clinic, alcoholics anonymous, detox centres, family medicine services.1–3

Strategies to Reduce Consumption

- Avoid your favourite drink

- Alternate between alcoholic and non alcoholic drinks

- Sip drinks, don’t gulp

- Start drinking later in the evening

- Dilute drinks with mixer

- Avoid drinking on an empty stomach 1

Pharmacotherapy in Alcohol Use Disorders

Anti-craving medications in AUD is associated with decreased inpatient days, emergency department visits and decreased overall healthcare costs.

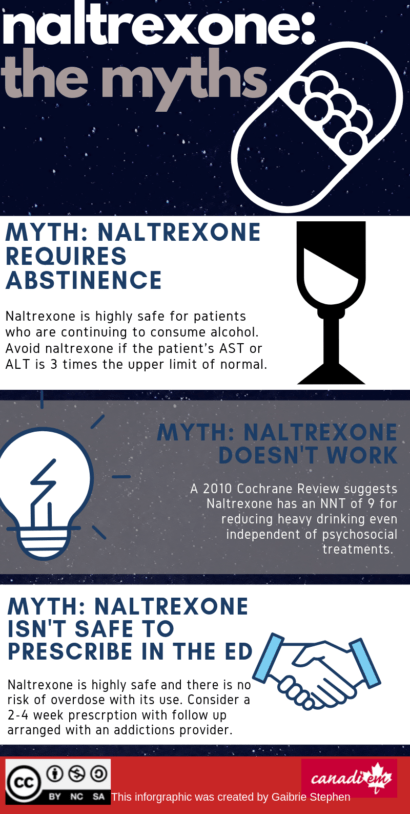

Naltrexone

Mechanism

- Competitive opioid antagonist thought to reduce the endorphin binding at these sites. Patients taking naltrexone therefore experience less pleasure from use of alcohol

Effectiveness

- A 2010 cochrane review shows a NNT of 9 for return to heavy drinking (>5 standard drinks per day in men or >4 standard drinks per day in women) 4**Comparatively ASA has a NNT of 50 in secondary prevention for ACS5.

Precautions

- Very safe and well-tolerated.

- Safety in patients with severe hepatitis or cirrhosis not well established. Avoid if the liver enzyme (ALT or AST) is 3 times the upper limit of normal.

How to Prescribe

- This medication is covered across Canada.

- Ensure patient is not in opioid withdrawal — naltrexone will potentiate this effect.

- Warn the patient about the most common side effect which is diarrhea and nausea

- Standard dose of treatment is 50mg per day. Consider starting 25mg daily for 3 days prior to 50mg daily dose to reduce GI side effects.

- Naltrexone can safely be started while the patient is drinking

- Prescribe 14-28 tablets of naltrexone and ensure follow up with a provider who can manage the prescription on an outpatient basis.

- You cannot overdose on naltrexone1.

Acamprosate

For patients who have contraindications to start of naltrexone there are other options, one of which is acamprosate.

Mechanism

This is a glutamate antagonist that works by reducing the subacute withdrawal symptoms associated with alcohol cessation (insomnia, dysphoria, cravings). Since the mechanism relies on relieving subacute withdrawal symptoms this medication’s efficacy is best when the patient has already been abstinent for several days prior to initiation.

Precaution

- Warn your patient about diarrhea which is the most commons side effect

- Avoid in severe renal insufficiency (CrCl <30) and pregnancy

How to Prescribe

- Similar to naltrexone, this medication is covered across Canada.

- Ensure the patient’s renal function is appropriate, the patient is not pregnant and is interested in abstinence (unlike naltrexone which does not require abstinence)

- Standard dose is 666mg oral, three times per day (a unique and interesting dose to remember!).

- Renal impairment or body weight <60kg suggests a decrease in the dose to 333mg oral, thee times per day1.

References

- 1.Kahan M. Safe Prescribing Practices for Addictive Medications and Management of Substance Use Disorders in Primary Care: A Pocket Reference for Primary Care Providers. Meta Phi. https://www.womenscollegehospital.ca/assets/pdf/MetaPhi/2017-04-03%20PCP%20pocket%20guide.pdf. Published 2017.

- 2.McGinnes RA, Hutton JE, Weiland TJ, Fatovich DM, Egerton-Warburton D. Review article: Effectiveness of ultra-brief interventions in the emergency department to reduce alcohol consumption: A systematic review. Emergency Medicine Australasia. July 2016:629-640. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.12624

- 3.Duong DK, O’Sullivan PS, Satre DD, Soskin P, Satterfield J. Social Workers as Workplace-Based Instructors of Alcohol and Drug Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) for Emergency Medicine Residents. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. May 2016:303-313. doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1164049

- 4.McAvoy B. Naltrexone Effective for Alcohol Dependence. Cochrane Review. https://www.cochraneprimarycare.org/pearls/naltrexone-effective-alcohol-dependence. Published 2010.

- 5.Walker G. Aspirin for Cardiovascular Prevention (After Prior Heart Attack or Stroke. The NNT. www.thennt.com/nnt/aspirin-for-cardiovascular-prevention-after-prior-heart-attack-or-stroke/.

EDITED on January 20th/2020: Clarification on use of naltrexone with opioids. Naltrexone is not to be used with someone who is using chronic opioids as it will potentiate opioid withdrawal.

Reviewing with the staff

Patients with alcohol use disorder present frequently to our emergency departments, and now more patients are admitted with complaints directly related to alcohol than those with ACS. Writing “discharge when alert, awake, and ambulating safely” is a missed opportunity to help our patients make a meaningful change. Along with SBIRTa conversation around the first line anti-craving medication naltrexone should be part of every encounter with every patient you see with alcohol use disorder. It is a widely available medication with an excellent number needed to treat for reducing heavy drinking days. It has few side effects and only contraindicated in severe acute hepatitis or in those on chronic opioid or opioid agonist therapy (methadone or buprenorphine). Deferring the prescription of naltrexone to an addiction medicine specialist or family physician may delay appropriate and effective treatment.