Rembrandt’s portrait of Gerard de Lairesse (1641–1711) (Click here to see full image)

In 1665, Rembrandt painted an honest portrait of his younger colleague Gerard de Lairesse, unknowingly immortalizing this painter’s unique physical appearance for contemporary speculation. Like Rembrandt, de Lairesse was a celebrated Dutch artist who was widely influential in his time for his French-style paintings. Today, many believe that he shows facial manifestations of this infectious disease. Do you know what disease he may have had?

While you’re giving it some thought, please consider taking 5 minutes to give us feedback on the “Spot the Diagnosis!” series. From newcomers to loyal fans, we would love to hear about how you use the series and what we can do to improve!

Click here to provide feedback on the “Spot the Diagnosis!” Series!

[bg_faq_start]What disease does this man have?

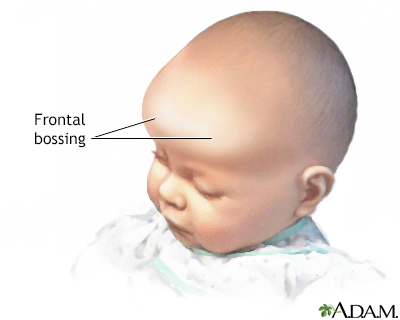

Gerard de Lairesse has uncharacteristically boyish looks for a 25-year-old man, with his large forehead and small bulbous nose. Based on the facial features depicted in this painting, he is widely speculated to have suffer from congenital syphilis. The late manifestations of this disease include the following facial deformities: 1) frontal bossing, 2) saddle nose, 3) short maxilla, 4) protuberant mandible1. In the painting above, de Lairesse presents with all of these features.

Left: frontal bossing, right: saddle nose

Unfortunately, de Lairesse completely lost his sight at 49 years old and was forced to give up his painting career for art theory. His blindness is speculated to due to late ocular complications from syphilis, potentially interstitial keratitis.1 However, for de Lairesse to have been as intelligent and successful as he was, his central nervous system must have been spared from his syphilis infection.

What is this disease and what are risk factors?

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete bacterium treponema pallidum. It is usually transmitted via direct contact with infectious lesions.2 Congenital syphilis is usually transmitted from the infected mother to the infant transplacentally, although it may also be passed to the infant at birth from direct contact with a lesion.3

Syphilis is known as “the great imitator” for its ability to present in a myriad of ways. Although the prevalence of syphilis is low in the general population, there should be high suspicion for this disease in patients with the following risk factors:2

- Men who have sex with men (81% of syphilis patients)4

- HIV co-infection

- Sexual partner tested positive for syphilis

What are the clinical stages of syphilis?

Syphilis is notoriously difficult to diagnose because its clinical manifestations vary drastically depending on the stage, from completely asymptomatic to a variety of potential complications involving different organ systems.

Primary syphilis is classically described as a single well-demarcated painless chancre (ulcer) at the point of sexual contact, sometimes associated with painless lymphadenopathy.5 The innoculation period is 3-90 days and the lesion generally resolves spontaneously in <6 weeks.6

Chancre on inner, upper lip

Secondary syphilis usually presents 3-5 months after the initial infection and occurs when the bacteria in the lesion enters the bloodstream via the lymphatic system. The clinical manifestations include 1) non-pruritic maculopapular rash of the palms and soles described as copper in colour, 2) painless lesions of the oral or genital mucosa, 3) general lymphadenopathy, and 4) constitutional symptoms, including fever, malaise, nausea, and headache.6

Asymptomatic maculopapular rash seen in secondary syphilis

Complications from secondary syphilis occur due to immune complex deposition in various organs.5 Ocular manifestations include uveitis, scleritis and keratitis and generally present with decreased visual acuity and “prostitute’s eye.” Ocular syphilis is highly worrisome for central nervous system infection and should be treated empirically for neurosyphilis. The ears, kidneys and liver may also be affected.6

Latent syphilis is an asymptomatic period that may last years and is non-infectious.5

Tertiary syphilis occurs in one third of untreated patients 5-25 years after the initial infection but is exceedingly rare in North America. It may have cardiovascular, gummatous and neural manifestations:

- Cardiovascular – aortitis is the most common diagnosis and presents with anginal-like pain or heart failure. It may result in an ascending aortic aneurysm and aortic valve regurgitation, although dissection is very rare.

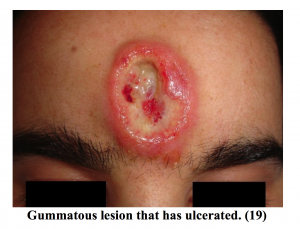

- Gummatous – granulomatous lesions of the skin, bone and organs.

- Neurosyphilis presents in a variety of ways. It is most commonly asymptomatic, but may present as general paresis or tabes dorsalis in late stages.

- General paresis – personality change, dementia, psychosis.

- Tabes dorsalis – affects posterior column of the spinal cord, resulting in ataxia and lancinating pain.6

What are the diagnostic tests?

There are two types of tests for syphilis. Non-troponemal tests, including RPR (rapid plasmin reagin) and VDRL (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory), are used for initial screening because they are fast and cheap. Treponemal tests such as FTA-ABS and dark field microscopy are generally not available at emergency departments but are used to confirm positive RPR or VDRL result.7

If neurosyphilis is suspected, a lumbar puncture should be performed to obtain CSF for VDRL or RPR testing. In addition, an elevated CSF lymphocyte count is suggestive of neurosyphilis.

Patients who test for syphilis should also be screened for HIV due to the high rate of co-infection, as well as other sexually transmitted infections such as gonorrhoea, chlamydia and hepatitis B.8

What is the treatment?

The best treatment for syphilis is Penicillin G. Primary and secondary syphilis is treated with a single dose of penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million units IM. If a patient is allergic to penicillins, penicillin desensitization is warranted; doxycycline is an alternative antibiotic. Patients who test positive for syphilis are required by public health to notify all sexual partners within 60 days of symptom onset.8

[bg_faq_end]Want more Spot the Diagnosis! posts? Click here!

References

- Johnson H. Gerard de Lairesse: genius among the treponemes. J R Soc Med. 2004;97(6):301-303. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1079501/.

- Syphilis – CDC Fact Sheet. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Published 2017. Accessed January 27, 2018.

- Dobson S. Congenital syphilis: Clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/congenital-syphilis-clinical-features-and-diagnosis. Published January 4, 2017. Accessed January 27, 2018.

- Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/Syphilis.htm. Published 2016. Accessed January 27, 2018.

- Barakat R. Syphilis in the ED: Presentations, Diagnosis, and Management of the Great Imitator – emDOCs.net – Emergency Medicine Education. emDOCs.net. http://www.emdocs.net/syphilis-ed-presentations-diagnosis-management-great-imitator/. Published August 10, 2017. Accessed January 27, 2018.

- Hicks C, Clement M. Syphilis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations in HIV-uninfected patients. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/syphilis-epidemiology-pathophysiology-and-clinical-manifestations-in-hiv-uninfected-patients. Published October 28, 2017. Accessed January 27, 2018.

- Hicks C, Clement M. Syphilis: Treatment and monitoring. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/syphilis-treatment-and-monitoring. Published August 15, 2017. Accessed January 27, 2018.

- Swanson J, Welch J. The Great Imitator Strikes Again: Syphilis Presenting as “Tongue Changing Colors”. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2016;2016:1607583. [PubMed]