You are midway through a busy shift when a colleague approaches you and utters the dreaded “Remember that patient you saw…?!”. This time, it is about an elderly patient you saw the previous week with chest pain that you sent home. And now they are back! You finish the rest of your shift – a bit distracted – and you start reflecting back on that patient. Did I miss anything? You wonder about what could be learned to improve your practice from patients that return to your emergency department (ED), and what the utility of that feedback truly is. Could it improve the quality of care of your patients? Is there a program in your ED for return visits or is there a regional program that supports these activities?

Welcome to another HiQuiPs special post, where we take a wider lens with QI in the ED. This two-part series discusses Ontario’s ED Return Visit Quality Program (RVQP), a provincial-level continuous quality improvement program.

Background

The ED environment often leads to disposition decisions made under imperfect conditions: limited information, language barriers, and a somewhat chaotic environment. We make these disposition plans, including discharge home, largely without much feedback afterwards to calibrate our judgement, and by extension improve our quality of care. If we do discharge patients home and they return, how does this reflect on our quality of care? Patients sometimes return to the ED after their initial visit for a variety of reasons. However, ED return visits that lead to an admission may be potentially high risk.1 There are a multitude of contributing factors such as condition persistence, adverse events due to initial treatment, missed diagnoses, persistent symptoms, physician errors, misdiagnoses, limited resources, fewer beds, no social worker present, or patient visits on a weekend.2–6 Patient characteristics that contribute to this include higher rates of old age, non-ambulatory status, and higher-grade triage.7 Moreover, patient reports have noted fear, uncertainty about their condition, and the perception of expedited care as contributing factors to their return.8

Therefore, it may be valuable for ED physicians to know of return visits of their patients – just as surgeons may want to know surgical site infection rates. But do return visits actually reflect quality of care?

Rationale

Unscheduled return visits are not synonymous with quality problems or provision of poor care.9 However, they can be used as triggers for quality improvement initiatives.10 Triggers are clinical events that may indicate the possibility of an adverse event.11 Therefore, unscheduled ED return visits can be used as a trigger to investigate the care provided in the initial ED visit for potential quality improvement opportunities.12

Not only is this an important potential source of feedback for individual providers, it may also be important at the departmental level as an opportunity to improve the environment or policies that support the provision of care. In addition, it may help instil a culture of quality and safety where providers are learning and sharing their adverse events and lessons learned with colleagues with the aim to improve care.

The focus of the program is not the rate of return visits itself but the opportunity to implement quality improvement initiatives to improve care. The overall philosophy of the ED RVQP is to “promote high-quality ED care by helping clinicians and hospitals identify, audit and investigate underlying causes of return visits to their ED and take steps to address these causes, preventing future return visits and harm”.13

History

The majority of return visit programs have historically focused on one ED.2,12,14,15 However, depending on the geographic location and mobility of patients, they may return to other acute care facilities or EDs for care after the initial visit. Internationally, linkage of these cases has been fraught with challenges on a population level (city, state, etc.). However, with increasing electronic record interoperability and data linkage algorithms, larger populations have been studied across hospitals, U.S. states, and large health information exchanges.16–18

In the Canadian context, provincial health insurance numbers, like in the province of Ontario, act as a unique identifier to enable linkage across the province and the ability to investigate return visits to any facility across the province. This allowed for the formation of Ontario’s ED RVQP, which began in 2016 and has spanned across 86 EDs in Ontario (including the 74 largest ones as part of a mandatory pay-for-result program). The program includes over 3.6 million ED visits per year (and over 36,000 return visits, i.e. approximately 1% of ED visits). It covers approximately 85% of Ontario’s ED visits.19

Return Visits

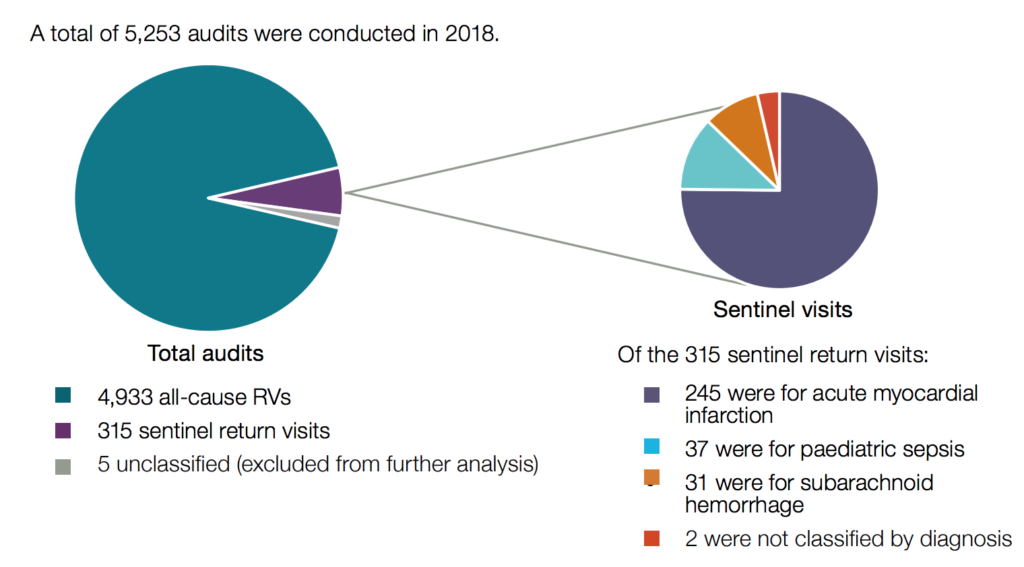

There are a variety of ways to investigate return visits, as a method is needed to choose which cases to audit since the majority may not reflect quality issues. The RVQP investigates two types of ED return visits:13

- All-cause ED return visits within 72 hours of discharge from the initial ED non-admit visit, to any of the hospitals in the province, and resulting in an admission to an inpatient unit on the second visit.20

- ED return visits within 7 days of discharge from the initial ED non-admit visit, to any of the hospitals in the province, resulting in an admission to an inpatient unit in the second visit with a sentinel diagnosis and with a related diagnosis documented in the initial ED non-admit visit. Sentinel diagnoses are associated with potentially high morbidity and mortality, and higher potential for QI initiatives. They include three specific diagnoses: pediatric sepsis, subarachnoid haemorrhage, and acute myocardial infarction, with a related diagnosis or presenting problem in the first visit (e.g., fever, headache, or chest pain, respectively).21–23

Reflection

In summary, Ontario’s ED RVQP is a provincial-wide continuous quality improvement program that allows ED providers to identify return visits to any ED in the province. These cases are then audited to identify any potential opportunities for QI initiatives. It is a large-scale program reflecting a priority to improve patient care.

Join us next time where we look at the program from a health informatics perspective and describe its architecture, as well as some of its accomplishments.

Special thank you to Ivan Yuen, Emily Hayes, and Lisa Fuller from Ontario Health, as well as Dr. Lisa Calder and Dr. Michael Schull for their input.

Senior Editor: Lucas Chartier

Junior Editor: Ed Mason

**UPDATE (November 2020): The HiQuiPs Team is looking for your feedback! Please take 1 minute to answer these three questions – we appreciate the support!**

- 1.Lerman B, Kobernick M. Return visits to the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1987;5(5):359-362. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(87)90138-7

- 2.Pierce J, Kellerman A, Oster C. “Bounces”: an analysis of short-term return visits to a public hospital emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(7):752-757. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81698-1

- 3.O’Dwyer F, Bodiwala G. Unscheduled return visits by patients to the accident and emergency department. Arch Emerg Med. 1991;8(3):196-200. doi:10.1136/emj.8.3.196

- 4.Wu C, Wang F, Chiang Y, et al. Unplanned emergency department revisits within 72 hours to a secondary teaching referral hospital in Taiwan. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(4):512-517. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.03.039

- 5.Verelst S, Pierloot S, Desruelles D, Gillet J, Bergs J. Short-term unscheduled return visits of adult patients to the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2014;47(2):131-139. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.01.016

- 6.McCusker J, Ionescu-Ittu R, Ciampi A, et al. Hospital characteristics and emergency department care of older patients are associated with return visits. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(5):426-433. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.020

- 7.Hu K, Lu Y, Lin H, Guo H, Foo N. Unscheduled return visits with and without admission post emergency department discharge. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(6):1110-1118. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.01.062

- 8.Rising K, Padrez K, O’Brien M, Hollander J, Carr B, Shea J. Return visits to the emergency department: the patient perspective. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(4):377-386.e3. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.07.015

- 9.Abualenain J, Frohna W, Smith M, et al. The prevalence of quality issues and adverse outcomes among 72-hour return admissions in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(2):281-288. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.11.012

- 10.Griffin F, Resar R. Global trigger tool for measuring adverse events (Second Edition). IHI. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/IHIGlobalTriggerToolWhitePaper.aspx. Accessed March 13, 2018.

- 11.Resar R, Rozich J, Classen D. Methodology and rationale for the measurement of harm with trigger tools. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12 Suppl 2:ii39-45. doi:10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_2.ii39

- 12.Gordon J, An L, Hayward R, Williams B. Initial emergency department diagnosis and return visits: risk versus perception. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(5):569-573. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70034-4

- 13.Introductory Guidance – the ED Return Visit Quality Program. Health Quality Ontario.; 2017:.

- 14.Cheng J, Shroff A, Khan N, Jain S. Emergency Department Return Visits Resulting in Admission: Do They Reflect Quality of Care? Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):541-551. doi:10.1177/1062860615594879

- 15.Zimmerman D, McCarten-Gibbs K, DeNoble D, et al. Repeat pediatric visits to a general emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28(5):467-473. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70107-5

- 16.Shy B, Kim E, Genes N, et al. Increased Identification of Emergency Department 72-hour Returns Using Multihospital Health Information Exchange. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(5):645-649. doi:10.1111/acem.12954

- 17.Duseja R, Bardach N, Lin G, et al. Revisit rates and associated costs after an emergency department encounter: a multistate analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):750-756. doi:10.7326/M14-1616

- 18.Jiménez-Puente A, Del R-M, Arjona-Huertas J, et al. Which unscheduled return visits indicate a quality-of-care issue? Emerg Med J. 2017;34(3):145-150. doi:10.1136/emermed-2015-205603

- 19.Chartier L. P037: the Ontario Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program: a provincial initiative to promote continuous quality improvement. CJEM. 2017;19:90. doi:10.1017/cem.2017.239.

- 20.Calder L, Pozgay A, Riff S, et al. Adverse events in patients with return emergency department visits. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(2):142-148. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003194

- 21.Vermeulen M, Schull M. Missed diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage in the emergency department. Stroke. 2007;38(4):1216-1221. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000259661.05525.9a

- 22.Schull M, Vermeulen M, Stukel T. The risk of missed diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction associated with emergency department volume. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(6):647-655. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.025

- 23.Vaillancourt S, Guttmann A, Li Q, Chan I, Vermeulen M, Schull M. Repeated emergency department visits among children admitted with meningitis or septicemia: a population-based study. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(6):625-632.e3. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.10.022

- 24.Health Quality Ontario. The Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program: Report on the 2018 Results. . Health Quality Ontario, Toronto; 2019:4.