Like all good trilogies, this too, must end. After a long hiatus due to budget negotiations, studio restrictions, and transitioning into staff-hood, it is time we discuss some of the complications that you may see from our pesky pacemakers in the emergency department (ED).

Before we begin, please review the prequels if you haven’t already. Check out Part 1, “Pacemaker Essentials: What we need to know in the ED” and Part 2, “Pacemaker Essentials: How to Interpret a Pacemaker ECG” . They are better than the Star Wars Prequels, promise.

THE CASE

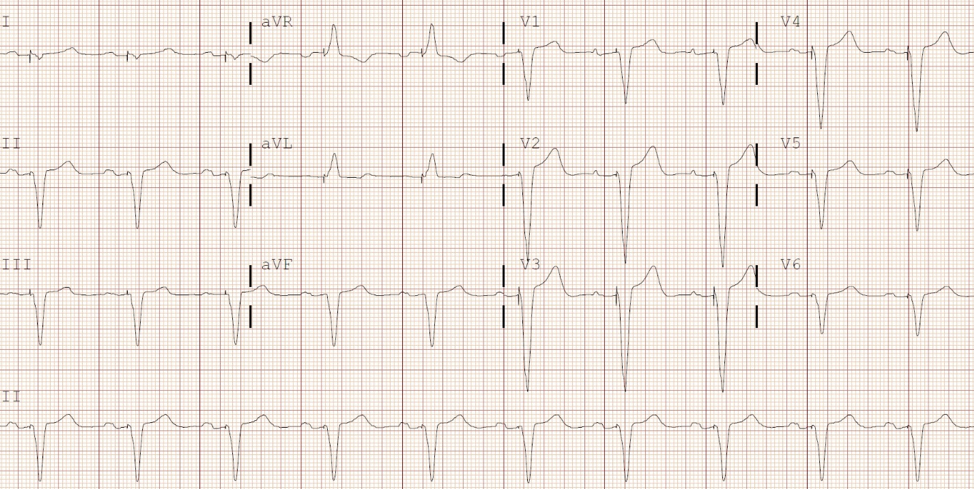

It’s 4 pm on a Tuesday and the triage nurse hands you an ECG. Your next patient is a 62-year-old female with pain and slight erythema over her pacemaker site. She had a permanent pacemaker implanted five days ago for intermittent complete heart block. She has no other relevant past medical history and her vital signs are normal.

Interpret the patient’s ECG

This patient’s ECG shows an atrial sensed and ventricular paced rhythm. Her P waves are normal but there is a long pause following each one; the PR interval is measured to be 250 milliseconds. Her pacemaker senses that the impulse is not conducted to the ventricles, so it delivers its own impulse and paces the patient. From her procedure note, you see that this patient had a DDD pacemaker inserted.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]What are 3 potential causes for her presentation?

- Expected post-procedural pain and erythema

- Pocket infection

- Systemic infection (e.g. endocarditis or bacteremia)

- Hematoma

You are reassured by her ECG – at least the pacemaker appears to be functioning normally. When you assess the patient, you note slight erythema and tenderness over the pacemaker pocket. You question if there is some fluctuance over the site. There is no murmur or systemic findings of endocarditis. You consider your differential above and order a chest x-ray and basic blood work including blood cultures. Now, back to the weak and dizzy patient in room six.

Complications

Before we move forward with this case, let’s discuss some of the more common pacemaker complications that we are likely to encounter in the ED. There are different ways to break these complications down. Some resources categorize complications based on whether they arose from the procedure itself and/or based on the timing of presentation. However, since many of these complications can occur at any time, we will focus on two categories: procedural complications and general complications.

Procedural Complications

- Bleeding/pocket hematoma

- Pneumothorax

- Hemothorax

General Pacemaker Complications

- Phlebitis, thrombophlebitis or deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

- Lead dislodgement

- Pacemaker malfunction

- Myocardial perforation

- Tricuspid regurgitation

- Pacemaker syndrome

Bleeding

Incidence: 0.5-3% 1

Description:

Most patients who undergo pacemaker insertion have minimal bleeding and the hematoma risk is low. Those who are on antithrombotic or anticoagulant therapy have slightly higher rates of bleeding and hematoma, but it still relatively rare.1

Management:

- Most hematomas are treated conservatively with a local compressive dressing.

- Exploration is ONLY indicated if the hematoma expands significantly and causes wound dehiscence and/or necrosis. However, exploring or draining a hematoma significantly increases the risk of infection so it should not be done haphazardly.1

- If you are concerned about a hematoma, you should consult cardiology and never attempt drainage by yourself in the ED.

Pocket or Systemic Infection

Incidence: 1-3.4% 2,3

Description:

Luckily infections are rare, but they can be detrimental to patients, especially if missed. Patients can have a pocket infection (where the pacemaker generator sits subcutaneously), systemic infection (e.g. endocarditis or bacteremia), or both. You should consider a systemic pacemaker infection in any patient with unexplained fever, bacteremia, pulmonary infiltrates or a pocket infection.4 Staphylococcus aureus or epidermidis are common culprit organisms.4–6

Management:

- Three sets of blood cultures

- Intravenous antibiotics (e.g. ceftriaxone and vancomycin)

- Cardiology consult –patients may require transesophageal echocardiography and removal and replacement of their pacemaker.

Tip 1: A pocket infection is endocarditis or bacteremia until proven otherwise!5

Incidence: 30-50%7

Description:

You may be surprised to find out how prevalent phlebitis and thrombophlebitis are with pacemakers. However, symptomatic presentations are rare because patients develop collateral blood flow (0.5-3.5%).7 If a patient presents with pain, swelling, or erythema to the ipsilateral arm (usually right-sided where pacemakers are often inserted) then a DVT must be considered.

Management:

- Usually, no treatment is needed for phlebitis or thrombophlebitis.

- Doppler ultrasound to rule out a DVT

- If the patient is confirmed to have a DVT, then they should be started on anticoagulation with the usual follow up for venous thromboembolism at your centre.

Pacemaker Syndrome

Incidence: 5-80%8

Description:

This syndrome is caused by the loss of atrioventricular (AV) synchrony. It is most commonly seen in VVI pacemakers where the atria and ventricles are not communicating. The atria contract against closed tricuspid and mitral valves resulting in increased jugular and pulmonary venous pressures, respectively. Patients can present with many, often vague, symptoms including fatigue, exercise intolerance, weakness, dizziness, palpitations, pre-syncope/syncope, and neck pulsations.7,8 Rarely, they can present in congestive heart failure (CHF).7

Management:

- All patients should receive cardiology follow-up as they usually require pacemaker interrogation. The severity of symptoms and clinical findings will determine whether the patient needs to be seen in the ED.

- If mild, patients may adjust to these new symptoms over time. Otherwise, they may require pacemaker parameter changes to decrease these symptoms.

- Some patients will go on to have their pacemaker changed to another type (e.g. VVI to a DDD).

- If the patient is in CHF, treat accordingly and consider other more common causes.

Tricuspid Regurgitation

Incidence: 16%9

Description:

Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) is a common pacemaker-related complication. It can occur from damage to the valve during pacemaker insertion or from the prevention of tricuspid valve closure during systole.9 Though it is not overly important for us to identify in the ED, it should be considered in those presenting with CHF. This problem should become less common if leadless cardiac pacemakers become more widely used (yes, you read that correct!).10

Management

- Loop diuretics (e.g. furosemide) are the first-line treatment for TR causing CHF.

- Consider consulting cardiology if the patient is not suitable for discharge. Otherwise, they should follow up with their cardiologist as an outpatient.

Lead Displacement

Incidence: 1-5%11

Description:

Lead displacement is not as rare as you may think. However, it is a rare reason for a patient to present to the ED. Patients can displace their pacemaker lead and even have myocardial perforation but remain asymptomatic! A chest x-ray (CXR) and ECG are two necessary investigations that may aid in diagnosis. There are two important caveats, however. First, if the patient’s native rhythm is normal, the pacemaker is inhibited so an ECG will not tell you about lead displacement. Secondly, a displaced lead may still be able to pace the endocardium so you could still see a paced rhythm. One helpful hint is if the patient’s paced morphology has changed from prior paced ECGs. Another helpful tip is if the paced ECG shows signs of malfunction, especially failure to capture, then lead displacement should be on your differential. A CXR can also be helpful for diagnosis. So carefully inspect the leads for any discontinuity in both your PA and lateral views.

Management:

- Any suspected lead displacement should be assessed by cardiology.

- Depending on the patient, they may adjust the lead, replace it, or leave it alone.

Tip 2: Consider lead displacement or perforation if the QRS morphology changes from a patient’s previously paced ECG.

Myocardial Perforation

Incidence: 0-6%12,13

Description:

If a patient with a pacemaker presents with chest pain, shortness of breath, or an equivalent, you should consider myocardial perforation on your differential diagnosis. As mentioned above, patients can even present asymptomatically! Patients can have perforation from the procedure itself or from the lead over time. Again, both an ECG and CXR are good starting points, with a CT scan being more sensitive than a CXR for detecting perforation if needed. For those who are savvy in point-of-care ultrasound, you may see a pericardial effusion and/or a lead floating outside the myocardium in the pericardial space.

Management:

- All perforations should be referred to cardiology and/or cardiac surgery. Evidence suggests that if a patient is asymptomatic no intervention is needed.14 Otherwise, it may be removed percutaneously or surgically depending on the case.

Pacemaker Malfunction

Incidence: Symptomatic malfunction <5%7

Description:

Pacemaker malfunction is a global term used when a pacemaker is not working properly. It usually involves failure of the pulse generator or the lead(s). It presents as failure to pace, failure to capture, inappropriate sensing (over- or under-sensing), or dysrhythmia. Inappropriate sensing and failure to capture are the two most common malfunctions.7 Life-threatening situations are rare with modern pacemakers due to longer lasting batteries, better fail-safe mechanisms, and frequent follow-up.7 Again, start with an ECG and CXR when considering malfunction. See Part 2 for more on pacemaker malfunction.

Management

- Pacemaker malfunction can be difficult to identify in the ED so patients should undergo a pacemaker interrogation if you are suspicious.

- If the patient is unstable, get the crash cart, place pads on the patient (at least 10 cm away from the pacemaker pocket), and proceed as per the ACLS algorithm.

BACK TO OUR CASE…

The patient’s blood work comes back within normal limits. Her blood cultures are pending. However, since you know that pocket infections can be devastating and difficult to diagnose early on, you consult cardiology with your concern. You hold off on broad spectrum antibiotics at this time so that cardiology can arrange for an aspiration of the pocket to guide antibiotic therapy.

You see the same cardiologist a couple days later who commends you on your great pick up. The patient’s blood cultures remain negative, but her aspiration sample was purulent and grew Staphylococcus aureus. The patient is currently on vancomycin and is scheduled to have her pacemaker removed and reimplanted on the opposite side. Great job outsmarting that pesky pacemaker!

Key take away points:

- Never attempt to drain a pocket hematoma in the ED!

- Most pocket and systemic infections require intravenous antibiotics and removal of the pacemaker.

- Phlebitis and thrombophlebitis are common but usually do not pose a problem due to collateralisation of veins. However, consider DVT in your differential for arm swelling or pain.

- Think of pacemaker syndrome whenever someone comes in with vague symptoms or CHF –especially if the pacemaker is new or has been recently adjusted.

- An ECG and CXR are always good starting investigations for pacemaker malfunction but findings may be subtle. If you suspect a malfunction, then patients should ultimately undergo a pacemaker interrogation.

This post was copyedited and uploaded by Kim Vella.

References

- 1.Nichols C, Vose J. Incidence of Bleeding-Related Complications During Primary Implantation and Replacement of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(1). doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004263

- 2.Olsen T, Jørgensen O, Nielsen J, Thøgersen A, Philbert B, Johansen J. Incidence of device-related infection in 97 750 patients: clinical data from the complete Danish device-cohort (1982-2018). Eur Heart J. 2019;40(23):1862-1869. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz316

- 3.Greenspon A, Patel J, Lau E, et al. 16-year trends in the infection burden for pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in the United States 1993 to 2008. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(10):1001-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.033

- 4.Karchmer A. Infections involving cardiac implantable electronic devices: Epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate . https://www.uptodate.com/contents/infections-involving-cardiac-implantable-electronic-devices-epidemiology-microbiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis?csi=d5cba49c-0116-49d8-b095-ecd863973113&source=contentShare. Published 2019. Accessed October 28, 2019.

- 5.Massoure P, Reuter S, Lafitte S, et al. Pacemaker endocarditis: clinical features and management of 60 consecutive cases. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30(1):12-19. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00574.x

- 6.Fakhro A, Jalalabadi F, Brown R, Izaddoost S. Treatment of Infected cardiac implantable electronic devices. Seminars of Plastic Surgery. 2016;30(2):60-65.

- 7.Marx J, Walls R, Hockberger E. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine-Concepts and Clinical Practice E-Book. 9th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- 8.Ausubel K, Furman S. The pacemaker syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103(3):420-429. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-103-3-420

- 9.Delling F, Hassan Z, Piatkowski G, et al. Tricuspid Regurgitation and Mortality in Patients With Transvenous Permanent Pacemaker Leads. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(6):988-992. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.12.038

- 10.Reddy V, Exner D, Cantillon D, et al. Percutaneous Implantation of an Entirely Intracardiac Leadless Pacemaker. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1125-1135. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1507192

- 11.Fuertes B, Toquero J, Arroyo-Espliguero R, Lozano I. Pacemaker lead displacement: mechanisms and management. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2003;3(4):231-238. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16943923.

- 12.Trigano J, Paganelli F, Ricard P, Ferracci A, Avierinos J, Lévy S. [Heart perforation following transvenous implantation of a cardiac pacemaker]. Presse Med. 1999;28(16):836-840. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10337335.

- 13.Banaszewski M, Stępińska J. Right heart perforation by pacemaker leads. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8(1):11-13. doi:10.5114/aoms.2012.27273

- 14.Vamos M, Erath J, Benz A, Bari Z, Duray G, Hohnloser S. Incidence of Cardiac Perforation With Conventional and With Leadless Pacemaker Systems: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017;28(3):336-346. doi:10.1111/jce.13140

Note: the featured image should be credited to implantate-schweiz.ch as outlined at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ICD_System.png under this CC license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ch/deed.en

Expert Review

A fitting conclusion to a highly informative trio of articles on a critical topic for every emergency physician.

Remember that a pacemaker—the generator and its wires—is a foreign body implanted in the body. Any concern for pocket infection must be worked up with systemic infection in mind—think “endocarditis until proven otherwise”. You should never attempt to incise the skin near or on top of the pacemaker insertion site—leave this invasive intervention to the experts.

Pacemaker syndrome and lead-related tricuspid regurgitation are tough diagnoses to make in the ED. Always suspect these pathologies when dealing with a patient who is in heart failure, but in the stable patient, the patient may only have vague symptoms. This underscores the need for expedited follow-up and asking your consultants the question: “could this be pacemaker syndrome or tricuspid regurgitation related?” You can’t diagnose a problem if you don’t suspect it!

One final plug for point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). The best window for assessing for pericardial effusion (if you are suspecting myocardial perforation) is the subxiphoid view. You’ve learned it in the context of the FAST exam, you can use it for this as well. Another note is that you should be able to visualize pacemaker leads sitting in the right ventricle in most standard cardiac views. Leads will appear as hyperechoic structures that produce significant shadowing artifact. Use it as a data point! Last, if you’re suspecting a pocket infection – use POCUS to determine if there’s an abscess. This could be extremely helpful in guiding management for your cardiology colleagues (does the patient need an incision and drainage or systemic antibiotics?)

While on the topic of cardiac devices, a quick reminder to check out Canadiem’s article on LVAD management in the ED (https://canadiem.org/lvads-approach-ed/). We will likely be seeing more of these devices implanted over the next few years and they carry their own host of complications for the emergency physician.

Leadless pacemakers? Whoa.