The Case

You are working a shift in the ambulatory zone of your emergency department. Your next patient is a 27 year old female with a chief complaint of “lower extremity injury”. On history, her right knee has been sore for the past 2 days, with swelling and worsening pain since last night, and she is now unable to weight bear on her right leg. She has no recent trauma, is not sexually active and her review of systems is otherwise normal. She has no past medical history, her vitals are stable and she is afebrile. On exam she can bear minimal weight on the affected leg and has pain on knee flexion as well as on palpation of the medial aspect of the knee. The knee is not edematous, warm, or erythematous, and there is no evidence of deformity or bruising. Tests for anterior collateral ligament (ACL), posterior collateral ligament (PCL), medial and lateral collateral ligament laxity and joint effusion are all negative. You report to your attending staff that you suspect the patient has a meniscal tear based on the finding of a positive Thessaly test, and would like to send her for an outpatient MRI. Your staff raises an eyebrow and asks you what this so-called “Thessaly test” is, and asks whether it is actually useful in detecting meniscal injury.

The Clinical Question

What is the “Thessaly Test” and has it been proven useful in the detection of meniscal injuries?

Meniscal Injuries

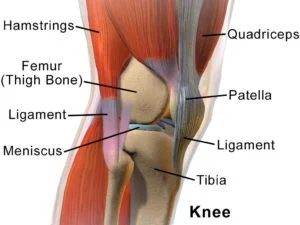

Meniscal injuries often occur following a twisting injury to the knee, usually with the foot planted on the floor.1 Common symptoms include joint line tenderness, a clicking noise, knee locking, and recurrent delayed joint effusions (most commonly with associated cruciate and/or patellar subluxation or dislocation). Many tests exist to help diagnose meniscal injuries, including the McMurray test, the Thessaly test, and joint line tenderness.2–4 We will compare the evidence for these tests below.

Figure 1. Lateral view of knee anatomy (left).5 Superior view of the right tibia (right); note location of the menisci.6

Commonly Used Tests for Detecting Meniscal Injury

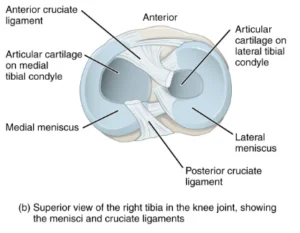

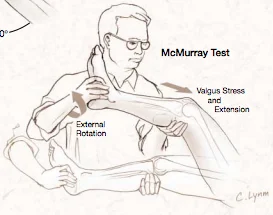

The McMurray Test

There are 2 components to the McMurray test, examining both the medial and lateral meniscus. Starting with the patient’s knee and hip fully flexed, apply a varus force (adduction) while passively internally rotating the foot and extending the knee simultaneously.2 A popping or clicking sound is a positive finding for a lateral meniscus injury. When assessing the medial meniscus, the stress applied is a valgus (abduction) force with passive external rotation and extension of the knee (Figure 2). McMurray test video demonstration

Figure 2. Testing of the medial meniscus using the McMurray test.7

Joint Line Tenderness

Pain on palpation of the knee joint line (between the femur and the tibia) is a positive test.2 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Testing joint line tenderness.8

The Thessaly Test

With the patient standing facing you, hold the patient’s outstretched hands while they bear weight on their affected leg only.2 The patient then flexes their affected knee to 20°, internally and externally rotating their body 3 times, using their knee as the pivot point. The test is positive if there is reproducible pain in the knee upon rotation (Figure 4). The test can be repeated with the knee at 5° of flexion, as well as on the opposite leg for comparison. Thessaly test video demonstration.

Figure 4. The Thessaly test at 20° knee flexion (left), and on external rotation at 20° knee flexion (right).3

The Evidence:

| Study | Thessaly Test | McMurray Test | Joint line Tenderness | |||||||

| MM | LM | MM | LM | MM | LM | |||||

| Sensitivity (%) | Harrison et al., 20099 | 90.3* |

| |||||||

| Karachalios et al., 20054 | 89 66^ | 92 81^ | 48 | 65 | 71 | 78 | ||||

| Konan et al., 200910 | 59 | 31 | 50 | 21 | 83 | 68 | ||||

| Meserve et al., 200811 | 55* | 76* | ||||||||

| Specificity (%) | Harrison et al., 20099 | 97.7* | ||||||||

| Karachalios et al., 20054 | 97 | 96 | 94 | 86 | 87 | 90 | ||||

| 96^

| 91^

| |||||||||

| Konan et al., 200910 | 67 | 95 | 77 | 94 | 76 | 97 | ||||

| 68^

| 89^

| |||||||||

| Meserve et al., 200811 | 77* | 77 | ||||||||

| Positive Likelihood Ratio | Harrison et al., 20099 | 39.3* | ||||||||

| Konan et al., 200910 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 22 | ||||

| 1^ | 1^ | |||||||||

| Jackson et al., 200312 | 17.3* | 1.1* | ||||||||

| Soloman et al., 20017 | 1.3* | 0.9* | ||||||||

| Negative Likelihood Ratio | Harrison et al., 20099 | 0.09 | ||||||||

| Konan et al., 200910 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.3 | ||||

| 0.9^ | 1^ | |||||||||

| Jackson et al., 200312 | 0.5* | 0.8 | ||||||||

| Soloman et al., 20017 | 0.8* | 1.1 | ||||||||

| Diagnostic Odds Ratio | Meserve et al., 200811 | 277 | 3.99 | 10.98 | ||||||

| Accuracy (%) | Karachalios et al., 20054 | 94-96 | 78-84* | 81-89* | ||||||

| 86-90^ | ||||||||||

^ Results for the Thessaly test at 5° knee flexion. All other Thessaly test values are at 20° knee flexion.

* Reported value did not distinguish between medial and lateral menisci

MM = medial meniscus

LM = lateral meniscus

Note:

– Likelihood ratio greater than 1 means the test is associated with the presence of the disease. A likelihood ratio less than 1 indicates that the test is associated with the absence of the disease. A likelihood ratio close to 1 indicates that the test is of little practical significance.

– Higher diagnostic odds ratios greater than one indicate better test performance. An odds ratio is defined as a measure of association between an exposure and an outcome, comparing the odds of an outcome occurring in the presence of an exposure versus with no exposure.13

Discussion:

With several tests to evaluate a potential meniscal injury, knowing which one to rely on can be challenging. As shown in the evidence above, the Thessaly test has a higher sensitivity and specificity than the McMurray test and joint line tenderness.4,9,10 The results demonstrate greater accuracy with the Thessaly test performed at 20° flexion than at 5° flexion.4,10 One study reported lower sensitivity and specificity values for the Thessaly test compared to the McMurray and joint line tenderness tests, however these results were for patients with simultaneous ACL and meniscal tears, indicating that perhaps the Thessaly test is best for detecting isolated meniscal injuries.14

While the Thessaly test is proving to be a valuable clinical tool in the detection of meniscal injury, other tests should not be disregarded.4,9,10 In fact, some studies are now suggesting that a combination of two techniques (i.e. Thessaly and joint line tenderness, or McMurray and joint line tenderness) is likely best.10 Each test provides its own set of advantages and disadvantages depending on the clinical situation, and further research is needed to further delineate the scenarios in which each test would be most useful. It is important to remember that while the Thessaly test has proven to be a clinically useful physical examination technique, the significance of a good clinical history cannot be overstated in any case!12

Summary

The Thessaly test is a relatively new physical examination technique for the detection of meniscal injury (both medial and lateral) in the emergency department.2 Clinical research has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for this test, especially when performed at 20° knee flexion. Moreover, compared to the more commonly taught McMurray test, the Thessaly test is much easier to perform and similarly easy to learn and teach.10 The general consensus among recent studies is that the Thessaly test should be the preferred method for detection of meniscal injury and is a useful clinical tool.4,9

Back to our Case

The evidence you show convinces your staff to send your patient home with a referral for an outpatient MRI, as well as an orthopedics follow-up. She is given crutches to assist with weight bearing, and is advised of symptomatic control (rest, ice, elevation, compression [RICE], and acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen for pain control, and straight leg raises). Her MRI is positive for a right medial meniscal tear and she is further managed by orthopedics.

Of note, since MRIs of the knee are associated with many false positives, you do not need an MRI to diagnose every meniscal injury, especially in older populations (although not the case in this example). The mechanism of injury and the history/physical exam are of utmost importance, even more so than imaging, when investigating a possible meniscal injury. Additionally, the natural history of isolated meniscal tears without locking/catching should repair within 6 months with conservative management (RICE and physiotherapy).

This post was uploaded by Sean Nugent (@sfnugent) and reviewed by Dr. Anita Pozgay, an emergency physician associated with McMaster University, who also suggested these references.15,16

References

Reviewing with the Staff

The gold standard to diagnose a meniscal tear is arthroscopy – both invasive and unreasonable to perform on every patient suspected of a meniscal injury. The Thessaly test is useful to perform during the physical exam of a patient with acute knee pain. It can however be difficult in a patient with significant knee pain or swelling, and should not be performed if any instability is detected in the joint. Both anecdotally and the evidence demonstrate the Thessaly test should not be used in isolation to diagnose meniscal tears. Used in combination with the joint line tenderness test, McMurray’s test or the Apley’s test can increase the likelihood of the correct diagnosis and appropriate management. Remember that while these are important physical exam tests to perform, in the presence of other knee pathologies, these tests are no longer accurate. Used in the right patient – with the history suspicious for a meniscus injury, the Thessaly test can be a useful test to perform.