Editor’s Note: This is part 1 of a 2 part series on patients with homelessness. Stay tuned for Part 2 which will deal with the intersection of homelessness and opiate drug use.

A 29-year-old male named Billy presents to your emergency department with a 4-day history of progressive leg tenderness. On exam, you note a poorly demarcated area of erythema on the leg which is warm and tender to the touch, suggestive of cellulitis. You give him a prescription for antibiotics and prepare to discharge him from the emergency department (ED). When you tell him that he can return home to recover from his infection, he informs you that he is currently experiencing homelessness and is staying in the shelter system. How do you arrange for follow-up care and treatment of an individual who is under-housed?

Background

In Canada, as of 2018, more than 235,000 people experienced homelessness in a given year with 25,000 – 30,000 on any given night.1 Less than half of the people experiencing homelessness had access to a family doctor, and most relied on the use of acute care services to receive care.2 These numbers are likely an undercount of today’s status of Canadian homelessness and reflect the ongoing needs our society faces.3,4

Homelessness is also associated with frequent visits to the ED,5 making the ED a key touchpoint for health services for people experiencing homelessness. The number of people experiencing homelessness in Ontario who have visited emergency departments has steadily risen in the past decade, with over 9,000 unique individuals visiting an ED in Ontario in 2017.1 These numbers continue to rise in the post-COVID era with increased challenges accessing care nationally.6 However, there are few programs which are targeted towards optimizing their care.

One key challenge is discharge planning. While many presentations in the ED can often be addressed with a new prescription and follow-up care, it can be quite difficult to arrange these for individuals who are returning to the streets.

The purpose of this piece is to highlight a unique program in Ottawa, Ontario which facilitates the provision of ongoing care to individuals experiencing homelessness.

Intervention

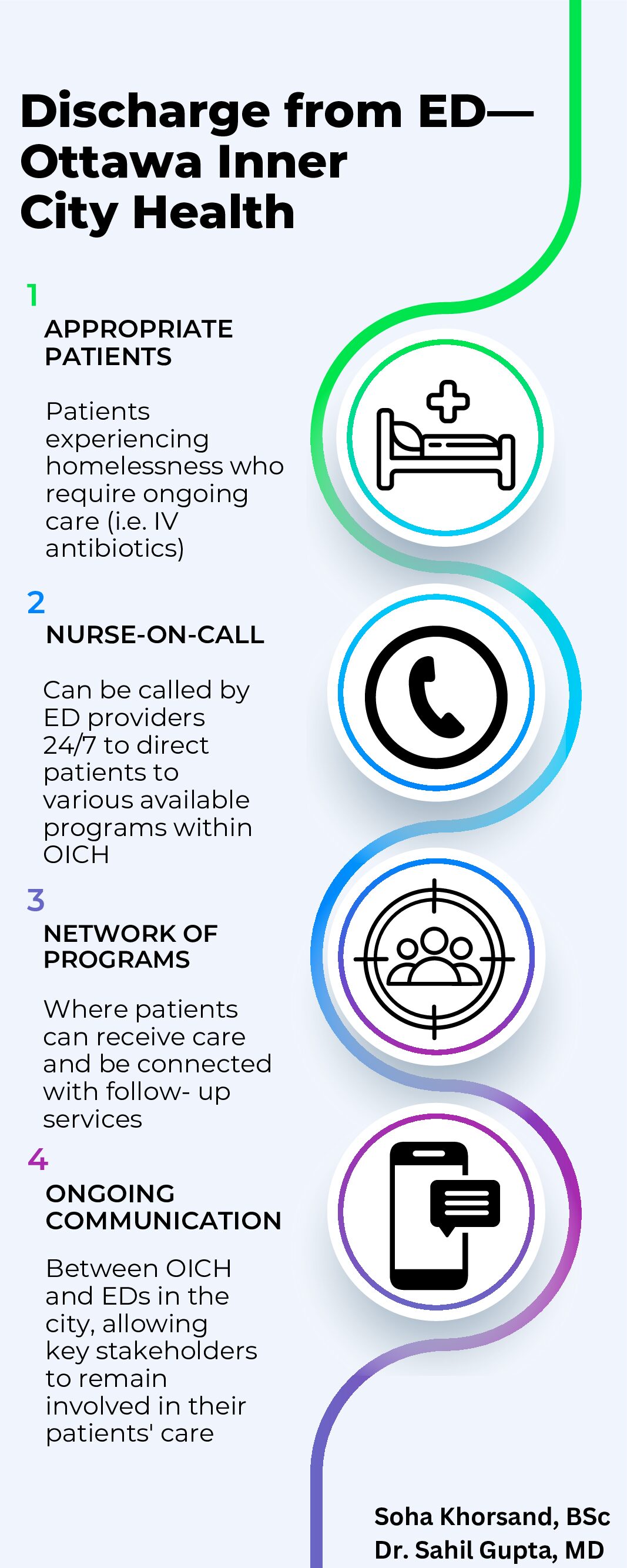

In Ottawa, Ottawa Inner City Health (OICH) is the unifying health system for individuals experiencing homelessness. They can be contacted directly by EDs to provide ongoing medical care to patients.

How it Happens

1. Appropriate Patients

Patients can be referred to OICH if they are identified as experiencing homelessness and require ongoing care at discharge. This care can include requiring parenteral antibiotics (IV/IM), further medication management, and wound care. The purpose of this program is to provide complete care to patients and help prevent re-presentation to the ED for a single issue (i.e. an ongoing worsening cellulitis). It’s important to note that not all people experiencing homelessness who enter the ED will be immediately directed to OICH. Those who only require shelter for the evening are directed back to the City’s central intake system and do not necessarily have to make contact with OICH.

2. Nurse-on-Call

At OICH there is an on-call nurse who is accessible by ED staff 24/7. Every ED in Ottawa has access to this number. While contact is usually made by a social worker in the ED, this number can also be used by any emergency physician or nurse if there is no social worker available.

When a patient is identified as requiring ongoing care, the nurse-on-call can be contacted to assist with discharge planning. From there, the nurse-on-call can determine whether there is appropriate programming available for the patient. Some factors considered include the medical necessity for ongoing care, the access of the patient to other resources (e.g., community resources, attachment to a primary care provider), and capacity in OICH Programs. If the patient is already known to OICH, this can also be used as a key factor to help determine which program would be most appropriate for them.

3. Network of Programs

Targeted Engagement and Diversion (TED)

A 24-hour monitoring service where individuals who are intoxicated can be monitored safely in the community for the duration of the acute phase of intoxication and avoid presenting to the ED. The unit is staffed by nursing, case workers, and mental health professionals, and can take up to 70 individuals per night. It is situated next door to one of Ottawa’s supervised consumption sites, making it readily available for those who need it, and has no barriers to the choice of substance used. Individuals can self-refer, refer a friend, or sign a consent with paramedics to be diverted to this program rather than being sent to the hospital for monitoring. Between January and March of 2023, 305 EMS calls were diverted to the TED program.7

Men’s Special Care Unit

A 30-bed unit with nursing staff where men experiencing homelessness can receive focused care for their physical and mental health. Most patients staying here are referred directly from the hospital. While admitted, patients can simultaneously receive assistance with applications for permanent housing through the City of Ottawa’s central intake system. Individuals in particularly precarious situations are able to stay at the unit for longer terms until a permanent housing option becomes available to them.

Dymon Health Clinic

A clinic led by nurse practitioners providing primary care to individuals who are experiencing homelessness or are street-involved. Most individuals being assessed by OICH will first be directed here. Across all programs at OICH, 2607 unique clients were provided with primary care services in 2023.7

4. Ongoing Communication

A centralized system for providing care to people experiencing homelessness helps make this program successful. Staff often become acquainted with patients and can provide longitudinal care. There is a constant line of communication between all EDs in Ottawa and OICH—with the social worker at one ED even having a WhatsApp group chat with the nurses at OICH to rapidly reach other.

This creates an open channel of communication, allowing ED providers to have the reassurance that their patients will be taken care of in the community, as well as creating an avenue for community partners to be able to signal to EDs when they send their patients over. This way all members of the care team can stay involved in the care of their patients. OICH also provides educational sessions to EDs in order to keep new ED staff informed of their role in the community.

Challenges

Unfortunately, like with many programs targeted towards people experiencing homelessness, there are ongoing capacity issues with OICH. While the demand ebbs and flows, there are many nights when there are not enough beds and a waitlist is required. Increased demands on the homelessness sector due to affordability and housing challenges8,9 along with an increased number of refugee applicants in Ontario have made it even more challenging for the program to keep up with demand.10 In addition, funds are often tied to particular objectives, which decreases program flexibility in tailoring to the specific needs of their populations.

Looking to the Future

The unique partnership between EDs and OICH is an example of an intervention built over many years of collaborative practice. Over the next few years, they are hoping to expand their programming to help meet healthcare needs in encampments, provide more supportive housing, and create a Women’s Special Care Unit to better serve the community.

Case Conclusion

You reach out to your social worker who calls the nurse-on-call at OICH. They determine that the Mens’ Special Care Unit would be a good fit for Billy to receive his medications and recover from infection in the community. They arrange for the transportation van to pick up your patient from the hospital and transport them back to the unit where they safely recover from their infection. You are able to provide clear written follow-up instructions for your patient, which the nurse at the Special Care Unit receives and helps coordinate.

This post was copyedited by Tim Zhang (@_timothyzhang).

References

- 1.Statistics Canada. Characterizing people experiencing homelessness and trends in homelessness using population-level emergency department visit data in Ontario, Canada. Published online 2021. doi:10.25318/82-003-X202100100002-ENG

- 2.Khandor E, Mason K, Chambers C, Rossiter K, Cowan L, Hwang S. Access to primary health care among homeless adults in Toronto, Canada: results from the Street Health survey. Open Med. 2011;5(2):e94-e103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21915240

- 3.Dionne M, Laporte C, Loeppky J, Miller A. A review of Canadian homelessness data, 2023. Statistics Canada. Published June 16, 2023. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75f0002m/75f0002m2023004-eng.htm

- 4.Blair N. Homelessness statistics in Canada. Made in CA. Published September 6, 2023. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://madeinca.ca/homelessness-statistics-canada/

- 5.Kushel M, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss A. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):778-784. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.5.778

- 6.Maretzki M, Geiger R, Buxton JA. How COVID-19 has impacted access to healthcare and social resources among individuals experiencing homelessness in Canada: a scoping review. BMJ Open. Published online August 2022:e058233. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058233

- 7.Annual Report 2022-2023. Ottawa Inner City Health; 2023:1-12. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://ottawainnercityhealth.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Annual-Report-2022-23.pdf

- 8.City of Toronto updates on shelter system pressures and calls for a sustainable, fair funding model to support people experiencing homelessness. City of Toronto News Release. Published May 31, 2023. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.toronto.ca/news/city-of-toronto-updates-on-shelter-system-pressures-and-calls-for-a-sustainable-fair-funding-model-to-support-people-experiencing-homelessness/

- 9.Mitchell D, LeBel J. How more homeless encampments in Ontario signal a housing crisis out of control. Global News. Published September 9, 2023. Accessed September 10, 2023. https://globalnews.ca/news/9926529/homeless-encampments-housing-crisis-ontario/

- 10.White-Crummey A. Migrant influx upsets plan to close pandemic-era shelters. CBC. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ottawa-physical-distancing-centres-grandmaitre-dempsey-1.6941588

Reviewing with the Staff

The case highlights a bread-and-butter case scenario seen across any ED in Canada. Arranging follow up care and navigating silos of care are challenging across the Canadian health system. For people experiencing homelessness, this becomes even more difficult – with added challenges such as access to a telephone or more pressing priorities related to daily tasks of survival and navigation. The simple success of a shared group-chat is a refreshing intervention that other places could learn from.

For many urban hospitals that serve a large number of people experiencing homelessness external (and often internal) referrals can be difficult to navigate. ED healthcare staff have limited knowledge base and interactions with the different agencies that care for people experiencing homelessness outside acute care. The experience is unfamiliar and unlike consulting a medical speciality such as Orthopedics. A low-barrier, central referral system through the Ottawa Inner City Health is a unique example to build mutual relationships that helps navigate appropriate care for people experiencing homelessness, while building relationships that improve communication between acute care and community health systems.