All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

CanMEDS Roles addressed: Medical expert

Case Description

You are assessing a patient in the emergency room who is presenting with a unilateral large pleural effusion that is causing hypoxia and shortness of breath. She needs a thoracentesis but her INR is 3.0 due to the Warfarin she takes for atrial fibrillation.

How can this procedure be performed safely? What about other common (non-neuraxial) bedside procedures (thoracentesis, NG tube, paracentesis, arthrocentesis) – when is it safe to perform these procedures while on anticoagulants (DOACs, Warfarin)?

Main Text

Thoracentesis-associated Risk

Case series of thousands of patients have demonstrated that thoracentesis has low rates of complications, even in patients with uncorrected coagulopathy from high INR due to oral anticoagulation, liver disease, severe thrombocytopenia or antiplatelet use 1 2 3. In these studies complications such as pneumothorax, re-expansion pulmonary edema, hemothorax, and tension pneumothorax (in intubated patients receiving positive pressure ventilation) occur at a rate of 1-5/1000. Hemothorax occurs at a rate of 1/1000 and does not appear to be affected by coagulopathy 4. Of patients who suffer hemothorax, the morbidity and mortality is low even in critically ill patients 5, with most complications managed conservatively 4. Additionally, having multiple risk factors for bleeding (such as renal disease, platelets <25, or an INR up to 6) is not predictive of patients who will suffer bleeding complications post-thoracentesis 4. Accordingly, transfusion therapy to pre-emptively correct INR prior to thoracentesis is costly, time consuming, likely has no effect on bleeding risk, and confers equal or higher morbidity from transfusion associated reactions (eg; transfusion associated cardiac overload – occurring at about a rate of 1/100, or transfusion associated lung injury at a rate of 1/1000).

Iatrogenic injury is the largest contributor to post-thoracentesis outcome. These risks can be minimized by good operator technique and use of bedside ultrasound 6. Small pigtail (6.0 French) catheters can be placed using a Seldinger method under ultrasound guidance to minimize the risk of iatrogenic injury (the gold standard for safe thoracentesis). That said, small studies have suggested that even placing larger tubes (20-24F) under ultrasound guidance is safe in patients on clopidogrel 7.

Supratherapeutic INR

In patients with supratherapeutic INR or severe thrombocytopenia, data is limited, but observational studies have captured hundreds of patients with INR up to 6 and platelets <25 and suggest few complications of thoracentesis despite lack of pre-treatment of coagulopathy 3.

Procedural bleeding risk stratification

For the reasons outlined above, routine correction of the INR with anticoagulant use for low risk procedures (bleeding rate <1%) is not recommended (Thrombosis Canada). Patients who arrive to the emergency room on anticoagulant medications have likely been determined to have greater risk for morbidity due to thrombosis than bleeding based on their CHADS2 and HASBLED scores, so discontinuing or reversing anticoagulation should not be routine for every procedure.

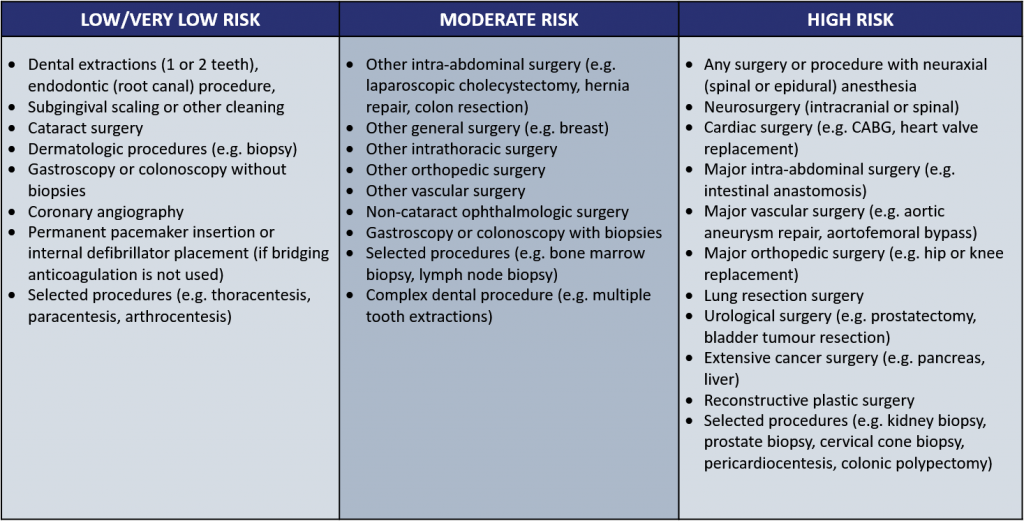

Based on data of bleeding complications in patients taking oral anticoagulants extracted from large scale clinical trials, the Thrombosis Canada Guidelines stratify surgical bleeding risk into three major groups:

From Thrombosis Canada

Most low-risk bedside surgical procedures such as thoracentesis, arthrocentesis, and paracentesis can be safely done in the emergency room without routinely reversing anticoagulation. If there is a rare bleeding complication, most are managed conservatively with coagulopathy reversed in major bleeding.

Approach to low risk procedures in anticoagulated patients in the ED

[bg_faq_start]1. Estimate the patient’s baseline risk of bleeding and clotting

- CHADS2 score – does the patient have high thrombotic risk?

- HASBLED score – does the patient have high bleeding risk?

- Obtain bleeding history

- Patients with normal coagulation tests can have propensity for bleeding that is apparent from previous procedures or from hereditary coagulopathy)

2. What is the anticoagulant history? (3 questions)

- See Blood & Clot post “When can patients on direection anticoagulants have surgery”

- What anticoagulant was taken?

- When was the last dose?

- What is the creatinine clearance?

3. Estimate the bleeding risk of the procedure

- Use Thrombosis Canada list to categorize procedural bleeding risk. Low-risk procedures typically have a <1% bleeding risk rate.

4. Review coagulation labs for highly abnormal values such as a supratherapeutic INR

- Little evidence exists for patients requiring urgent, low bleeding risk intervention with a very high INR. These must be managed on a case-by-case basis.

- Surgical technique is paramount – consider IR-guided thoracentesis

5. Discuss risks and benefits of procedure without reversal in patient needing urgent intervention.

- Major complications can be managed, while prophylactic reversal carries risks (thrombosis, transfusion reactions)

6. Monitor the patient and follow-up for complications.

Case Conclusion

The patient had an INR within therapeutic range and no history of bleeding with previous low-risk surgical procedures. A small bore percutaneous chest drain placed for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes under ultrasound guidance in the emergency room with consultation with internal medicine for further management of her effusion and inpatient monitoring for post-drainage complications.

Main Messages

- In otherwise low bleed risk patients undergoing low-risk surgical procedures, anticoagulation does not need to be stopped

- In low risk surgical procedures, patient factors such as history of coagulopathy or iatrogenic injury from surgery create a higher risk for bleeding than anticoagulant factors

- In higher risk patients, low-risk surgical procedures that cannot be delayed can be performed safely with appropriate risk/benefit discussion and follow-up monitoring for post-procedure complications

All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

This post was reviewed by Brent Thoma, Teresa Chan, Sean Nugent and copyedited by Rebecca Dang.