All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

CanMEDS Roles addressed: Medical expert, Manager

Case Description

You are called to assess an active and energetic 79 year old man who has come to the ER complaining of palpitations for three months. You do an EKG which shows atrial fibrillation. The patient has a history of gout, hemorrhoids, hypertension, and diabetes. His only medications are a thiazide diuretic and insulin. You feel his annual stroke risk is high enough to merit stroke prevention. He’s interested in starting an anticoagulant, but his creatinine is 245 umol/L, and his weight is 25 kg. This gives him a creatinine clearance of 15 mL/minute. Which anticoagulant should you prescribe? What if his creatinine clearance was 30? Or 10? What if he was on dialysis?

Main Text

In the last decade, the treatment options for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation have increased. Where we previously relied on just warfarin and aspirin for oral treatment, we now have access to a host of newer, targeted agents such as DOACs (direct oral anticoagulants) including a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran) and three direct Factor Xa inhibitors (apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban). Unlike warfarin, the DOACs have predictable dosing and don’t require lab monitoring. But there’s a catch: they are all dependent, to some extent, on renal excretion. In patients with acute and chronic renal insufficiency, there is a risk of drug accumulation, which leads to increased bleeding risk. To complicate matters further, patients with chronic kidney disease have a baseline increased risk of both bleeding and clotting; uremic toxins, anemia, and hemodialysis (HD) affect coagulation factor and platelet function, while the risk of arterial and venous thrombosis is increased two- to five-fold1 2 3.

How can you ensure that your patient with renal insufficiency gets the safest and most effective anticoagulant for them?

Know your Drugs

Warfarin

At first glance, a vitamin K antagonist like Warfarin is the easiest option for patients with renal insufficiency. It won’t accumulate and levels are easily monitored with an INR. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to dose in patients with advanced CKD as the INR tends to fluctuate more often than in patients without advanced CKD. Some studies also showed an increased risk for strokes and bleeding with VKA therapy in patients with advanced CKD, especially in patients older than 75 years. Warfarin is a reasonable choice in renal insufficiency if the INR can be monitored carefully, and the patient can maintain a stable INR range most of the time.

DOACs

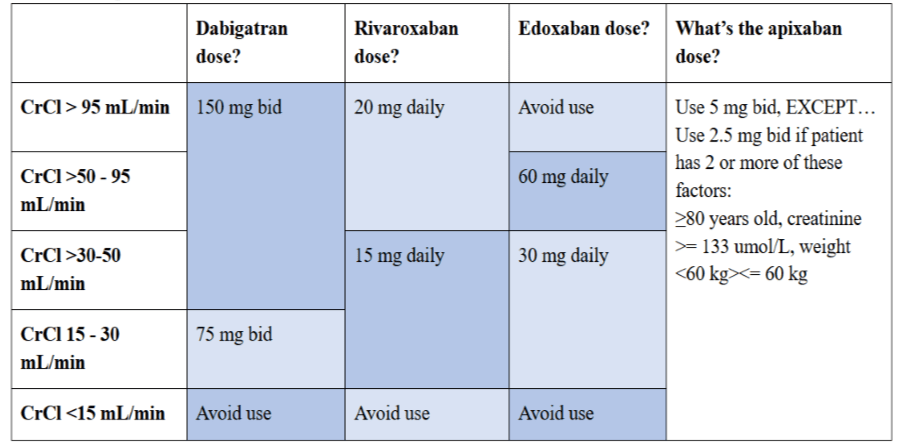

DOACs are a trickier choice. A recently published meta-analysis looked at ∼14,000 patients with AF and moderate CKD (GFR >=30 mL/min). DOACs appeared to be more effective at reducing strokes and systemic embolism and had a slightly better bleeding safety profile when compared to warfarin 4. However, each DOAC behaves differently in the setting of renal dysfunction 5. Use the guide below!

DOAC Dosing in Atrial Fibrillation

What about hemodialysis?

There is a paucity of published data on DOAC use in patients with severe renal failure and/or dialysis. Most thrombosis specialists try warfarin first, to see if it’s tolerated. If not, apixaban should be used as it is the only DOAC with pharmacologic studies in this patient group. A helpful commentary published in The Hematologist suggests the lower dose of 2.5 mg bid in the hemodialysis patient, and encourages physicians to inform their patients fully so they can make a shared decision around anticoagulation.

Don’t “set it and forget it”

A partially-evidence-based axiom: Renal function deteriorates over time. A post hoc analysis of the 18,000+ patient RE-LY trial showed that CrCl deteriorated over time in both the dabigatran and warfarin arms 6. Patients get older, nephropathic diseases like diabetes and hypertension (generally) get worse, and a CrCl of 30 can turn into a CrCl of 20 in the blink of an eye. Every patient on long term anticoagulation – especially if they have CKD – should have regular monitoring of renal function. If the CrCl changes, dose adjustment (or a drug switch) should occur. Finally, if a patient is teetering on the cliff of severe renal insufficiency, consider using a drug that can handle the fall.

Do the math

Most clinicians use the estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) rate, calculated by the laboratory, as a quick measure of renal function; however, the recommended doses of all currently approved DOACs are based on the CrCl calculated with the Cockroft-Gault equation. There can be significant discordance in DOAC dosing if you use the eGFR instead of the Cockroft-Gault equation. So, take the time to calculate the CrCl. Use actual body weight unless the patient has a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Obese individuals should have a CrCl range calculated, using both an ideal and actual body weight; they should then get the DOAC dose that best balances their bleeding and clotting risks.

Case Conclusion

Your patient’s CrCl of 15 mL/min makes rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and dabigatran risky choices; all are contraindicated if the CrCl slips even a little further. You explain to your patient that apixaban use doesn’t depend on the CrCl alone, so he is a candidate for the 2.5 mg bid dose. He’s also a candidate for warfarin.

Your patient likes the idea of apixaban, but is unable to afford this medication. You explain to him that apixaban in atrial fibrillation is covered under most provincial drug benefit plans for older patients. Your patient would receive coverage in your province. He would like to discuss his options further with his family physician, and is confident he can get in to see her in the morning. You write a note to her, recapping your discussion around drug options – and you remind the patient that whatever he chooses, he should have his kidney function monitored regularly.

Main Messages

- All anticoagulants are a safe and effective option in mild and moderate kidney disease

- If the CrCl is <= 50 mL/min, make sure you’re using the right drug at the right dose

- Monitor renal function regularly in the anticoagulated patient and calculate the CrCl using the Cockroft-Gault formula

All the content from the Blood & Clots series can be found here.

This post was reviewed by Brent Thoma, Mark Woodcroft and copyedited by Rebecca Dang.