In this article, we will dive into the world of abdominal wall pain – specifically from a condition called Abdominal Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (ACNES) – a diagnosis rarely considered when seeing patients with abdominal pain in the ED.

Case

Your next patient is Ms. Amanda Cnes, a 34-year-old female with abdominal pain. Before seeing the patient, you have a flip through her chart. She has had numerous ER visits for abdominal pain over the last year, all of which have yielded normal investigations. She has multiple consultation notes from specialists who have been unable to identify a cause for her pain. Her imaging including CT and MRI have been normal. She has even had a normal liver biopsy. You see the patient, and she reiterates her frustration about the lack of diagnosis, and that “the pain has flared up again.” She is noticeably uncomfortable when attempting to lie on the examination table, and reports nausea associated with the pain.

Background

ACNES has an absolute prevalence estimated at 1/1800 adults1 and an unknown prevalence in children.2 One retrospective study found that 2% of patients presenting with abdominal pain to the ED were eventually diagnosed with ACNES.1 Other studies show that the prevalence of ACNES or other abdominal wall pain syndromes was 10-30% after patients had a negative diagnostic workup to exclude other causes.3,4 Despite this, ACNES is poorly understood and rarely diagnosed.2,5

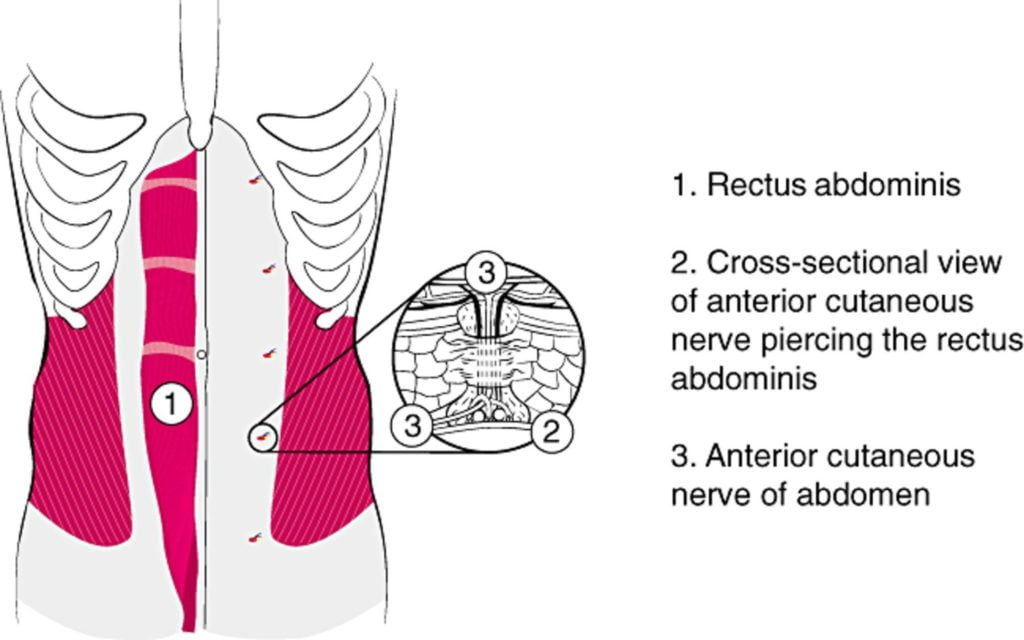

Risk factors for ACNES include gender (4:1 female prevalence)6 and differ when presenting in adults (risk factors: 30-50 years old, recent physical activity, overuse of abdominal wall muscles, obesity, ascites, and pregnancy)7–9 versus children (risk factors; abdominal surgery, trauma, or scarring).10 ACNES is caused by the entrapment of branches of the intercostal thoracic nerves as they move through foramina medial to the lateral border of the rectus abdominus. This entrapment causes ischemia of the nerve and therefore pain.11–13

Diagnostic Features:

Prior to considering the diagnosis of ACNES other dangerous causes of abdominal pain should be considered and ruled out with some degree of certainty. While it is a difficult diagnosis to make with certainty given the lack of high-specificity tests, there are numerous elements of the history and physical exam that point to ACNES as a potential diagnosis. They have been outlined in two tables:

Table 1. Historical features consistent with ACNES11

| Character of pain | Sharp/stabbing/burning |

| Precipitating factors | Worse with use of abdominal muscles and palpation |

| Location | Usually in the RLQ, but can be present elsewhere14 |

| Time course | The pain can be acute, chronic, or an acute exacerbation of chronic pain |

| Associated symptoms | Can have nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite |

| Any previous investigations? | Usually a long clinical course and many unnecessary investigations but can present as a first episode of pain. |

Table 2. Physical exam features consistent with ACNES11

| Point tenderness in one or more locations | <2 cm in diameter. Use your finger or a q-tip to determine the location. |

| Hypo/hyperesthesia of the surrounding skin | Pinch for pain, stroke with cotton swab for light touch, use an alcohol swab for cold sensation |

| Carnett’s Sign | Place the patient supine on a flat examination table. Ask them to raise their head and shoulders off the bed (thus activating the abdominal muscles). In a positive test, pain will increase and is pinpointed with a fingertip or cotton swab. A visceral cause of pain (ex: cholecystitis, etc) may decrease with this maneuver. |

When history and physical exam point to ACNES as a likely cause, the diagnosis can be confirmed with an ultrasound-guided nerve block into the tender point performed by a practitioner familiar with and skilled in the procedure. The following drop-down menu outlines a protocol for performing the injection (Editor’s note: Our standard disclaimers apply – please seek out appropriate training and guidance before performing the procedure independently).

[bg_faq_start]The injection protocol for ACNES:

- With the patient lying supine, precisely locate the tender point(s) by poking in the tender area with a q-tip or your finger. Mark their location(s) with a pen. The tender point will be less than two centimeters in diameter and have a positive Carnett’s sign and hypo/hyperesthesia of the surrounding skin (see Table 2). Precise identification of the tender point location(s) is required for diagnosis.

- Draw up 2-10mL of 1% lidocaine or 0.25% bupivacaine per tender point and grab a 26-gauge needle for injection.14

- Note: if you strongly suspect ACNES as a diagnosis, you can consider adding steroid like triamcinolone 20-40mg or methylprednisolone 40mg to your syringe of local – since these medications are used to treat ACNES if your diagnosis is correct, thus saving a second poke.11

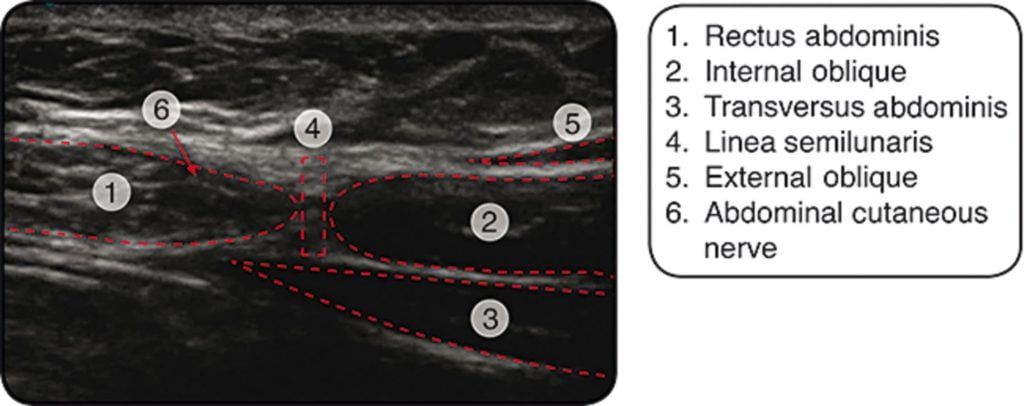

- Grab your friendly portable ultrasound machine – the purpose of this is to identify the nerve, assist with injection, and prevent intra-abdominal injection of your local. A high-frequency linear probe is best to image the abdominal wall.15 Place the transducer over linea alba in the transverse plane to identify the hypoechoic rectus fascia15. Slide the probe laterally until a view of the lateral edge of the rectus muscle and the linea semilunaris are visualized.15 The abdominal cutaneous nerve can be identified as a “hyperechoic dot” just medial to the linea semilunaris (0.5-1.0cm).15 The location of the nerve should correspond to a previously marked tender point.15

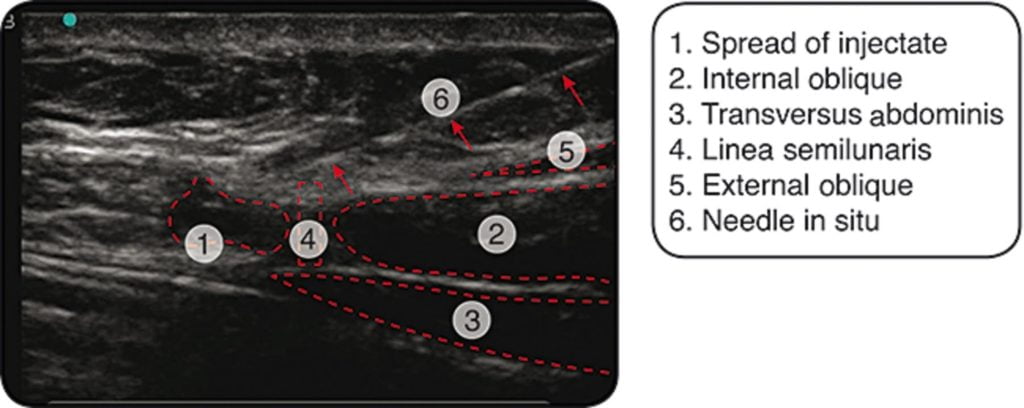

- Advance the needle in the longitudinal axis to the probe to visualize its course though the abdominal wall.15 Advance the needle until it reaches the abdominal cutaneous nerve then infiltrate generously with anesthetic (+/- steroid).15 One paper used 3 mL of anesthetic with each ultrasound guided injection procedure.15 Of note, some clinicians will perform the injection without the use of ultrasound and some may use differing techniques.

A >50% reduction in pain after this injection strongly supports a diagnosis of ACNES.11 In fact, approximately 86% of patients will be correctly diagnosed by this method. Most people will feel their pain return once the local anesthetic wears off, but approximately 20% will have an extended reprieve from their pain if a steroid was used in the injection.14,16

Note: there are a few other methods of diagnosing and treating this pain that are included in the literature including transversus abdominus plane block and rectus plane block. If you feel comfortable performing these blocks, they may also be indicated.

Disposition:

On physical exam of Ms. Cnes, she is tender in the right lower quadrant. The pain is very severe with reactive guarding, but not consistent with other features of peritonitis. There is no evidence of a mass or organomegaly. Using a q-tip, you identify a single tender point on the lateral abdomen where the pain is most severe. By moving the q-tip only 2cm away from the center, the same amount of pressure yields very mild tenderness. She is very tender even when you palpate the tender point when she lifts her head and shoulders off the bed (positive Carnett’s sign). Next, you use an alcohol swab to check cold sensation over the area and compare it to the other side. You also use a q-tip to test light touch sensation. She reports that the skin over the affected area does not feel as cool with the alcohol swab, and the area feels slightly numb to light touch. You discuss your suspected diagnosis of ACNES and recommend an ultrasound-guided nerve block. After gaining informed consent, you identify the nerve on ultrasound and infiltrate the area with bupivacaine and triamcinolone. You return twenty minutes later to a very excited patient who is pain-free and relieved to have a diagnosis.

Patients with ACNES will need follow up to provide continuous treatment. An in-depth discussion of the management of ACNES is beyond the scope of this article, but these patients will typically receive a few injections of steroid, followed by an ablation or surgical resection of the painful nerve. If you suspect or diagnose ACNES, you should refer as an outpatient to Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation or your local pain clinic.

Conclusion:

If you still think that ACNES is rare, compare the incidence (1/1800) to that of appendicitis (4.2/1800)17. Although the condition is relatively benign, it is still worth knowing about; if you can correctly diagnose these patients, you will prevent them from re-presenting to your emergency department for another expensive workup (and help them too because pain sucks!).

Helpful videos

Description of the condition: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8n5q7gM7KU

Physical exam and injection: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bDyX3myA0Gw

Injection procedure: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-18ztk4aGHU&t=42s

References

- 1.van A, Brouns J, Scheltinga M, Roumen R. Incidence of abdominal pain due to the anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome in an emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23:19. doi:10.1186/s13049-015-0096-0

- 2.McGarrity T, Peters D, Thompson C, McGarrity S. Outcome of patients with chronic abdominal pain referred to chronic pain clinic. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(7):1812-1816. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02170.x

- 3.Srinivasan R, Greenbaum D. Chronic abdominal wall pain: a frequently overlooked problem. Practical approach to diagnosis and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(4):824-830. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05662.x

- 4.Thomson H, Francis D. Abdominal-wall tenderness: A useful sign in the acute abdomen. Lancet. 1977;2(8047):1053-1054. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91885-2

- 5.Thompson C, Goodman R, Rowe WA. Abdominal wall syndrome: A costly diagnosis of exclusion. Gastroenterology. Published online April 2001:A637. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(08)83167-8

- 6.Costanza C, Longstreth G, Liu A. Chronic abdominal wall pain: clinical features, health care costs, and long-term outcome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(5):395-399. doi:10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00124-7

- 7.Meyer G, Friedman L, Grover S. Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. UpToDate. Published September 2020. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/anterior-cutaneous-nerve-entrapment-syndrome?search=abdominal%20cutaneous%20nerve%20entrapment&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H2

- 8.Lindsetmo R, Stulberg J. Chronic abdominal wall pain–a diagnostic challenge for the surgeon. Am J Surg. 2009;198(1):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.10.027

- 9.Peleg R, Gohar J, Koretz M, Peleg A. Abdominal wall pain in pregnant women caused by thoracic lateral cutaneous nerve entrapment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;74(2):169-171. doi:10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00114-0

- 10.Peleg R. Abdominal wall pain caused by cutaneous nerve entrapment in an adolescent girl taking oral contraceptive pills. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(1):45-47. doi:10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00034-2

- 11.Akhnikh S, de K, de W. Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): the forgotten diagnosis. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173(4):445-449. doi:10.1007/s00431-013-2140-2

- 12.Applegate W. Abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. Surgery. 1972;71(1):118-124. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4332389

- 13.Grover M. Chronic Abdominal Wall Pain: A Missed Diagnosis. University of North Carolina; 2008:1-3. https://www.med.unc.edu/ibs/files/2017/10/winter_2008_digestweb.pdf

- 14.Boelens O, Scheltinga M, Houterman S, Roumen R. Management of anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome in a cohort of 139 patients. Ann Surg. 2011;254(6):1054-1058. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822d78b8

- 15.Kanakarajan S, High K, Nagaraja R. Chronic abdominal wall pain and ultrasound-guided abdominal cutaneous nerve infiltration: a case series. Pain Med. 2011;12(3):382-386. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01056.x

- 16.Skinner A, Lauder G. Rectus sheath block: successful use in the chronic pain management of pediatric abdominal wall pain. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007;17(12):1203-1211. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2007.02345.x

- 17.Addiss D, Shaffer N, Fowler B, Tauxe R. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910-925. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115734

Reviewing with the Staff

I see a number of people with abdominal pain referred from GI who have essentially ruled out an intraabdominal process. When I inject for this issue, I use very little anesthetic, only about 2ccs, as I feel that the less you use the more likely you can convince yourself of a positive local response. Too much will diffuse out and may inadvertently anaesthetize other structures. While this may still be positive, your confidence of it being localized is diminished. Lastly (relating to your final point), abdominal wall pain can cost the system greatly through multiple consultations and investigations, while one simple injection is quite inexpensive. As such an injection may reduce overall medical burden on the system, and of course the patient.