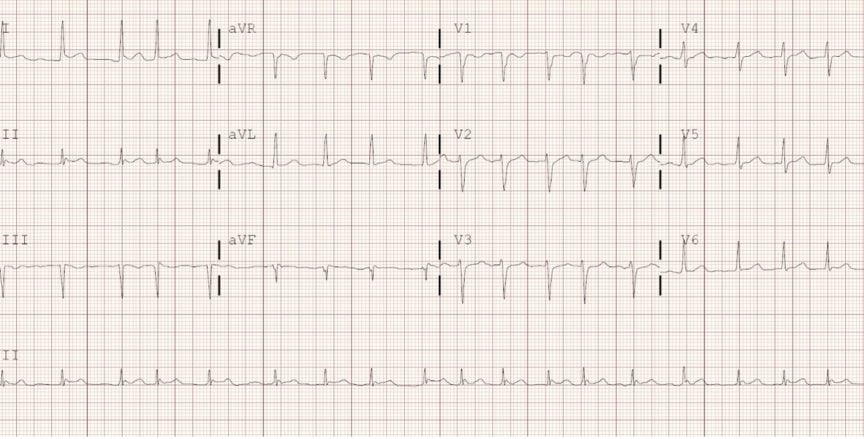

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia with a prevalence of 1-2% in Canada.1 On an ECG, AF is recognized by an irregularly irregular rhythm lacking p waves (Figure 1). In addition to the clinical and pathophysiological pattern, AF can be categorized as “valvular AF” (VAF) or “nonvalvular AF” (NVAF). While there are varying definitions for VAF, it is usually restricted to AF in the presence of a mechanical heart valve, moderate to severe mitral stenosis, or mitral stenosis due to rheumatic heart disease. Otherwise, it is termed NVAF. The distinction is important due to the inherently greater risk of thromboembolic events in VAF patients.2

The Guidelines

In 2018, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) published a Focused Update on their clinical practice guidelines for the management of AF and CAEP responded by releasing their own AF position statement.3,4 In 2020, CCS published an additional, more comprehensive, update to their AF guidelines.2 Prior to 2018, the two organizations had largely agreed upon their recommendations for managing emergency AF, however, the updates guidelines now differ in two key areas.

Both guidelines state that a recent stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) within the last 6 months preclude stable patients from cardioversion as their stroke risk is too high. Similarly, they both recommend cardioversion can be safe up until 48 hours, but the first key difference relates to the eligibility and timing of safe cardioversion for AF patients who present without prior anticoagulation. CCS suggests only cardioverting patients with NVAF who present within 48 hours if their stroke risk is low (defined as CHADS2 < 2). They state that patients who have a CHADS2 score of 2+ should only be cardioverted within 12 hours of AF onset. CAEP also limits cardioversion to within 48 hours if patients are at low risk of stroke or TIA, but they use CHADS-65 as their risk assessment tool. In addition, instead of the 12 hours set by CCS, CAEP permits cardioversion within 24 hours of AF onset for patients with higher risk of stroke (i.e., CHADS-65 is 2+).

The other key difference is the recommendation around anticoagulation therapy after pharmacological or electrical cardioversion. CCS suggests that all patients should receive 4 weeks of anticoagulation therapy after cardioversion, irrespective of their CHADS-65 score. This is because cardioversion, in and of itself, is a risk factor for stroke. In contrast, CAEP favors only prescribing anticoagulants to patients who meet one or more of the CHADS-65 criteria given that these medications are not without risk or costs. Both agree that it is important to consider patient factors and to use shared decision making.

These recommendations are major practice changes for emergency physicians (EPs) but they are both based on “low quality evidence” according to the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) standards.5 Specifically, the recommendation to restrict cardioversion to within 12 hours of onset in patients at higher risk of stroke is based on results from small sample sizes that somewhat conflict with the pathophysiology of AF.6,7 CCS and CAEP both advocate for the consideration of patient factors and shared-decision making in the clinical practice, however, the discrepancies between their stances on cardioversion and anticoagulation may lead to medicolegal ramifications, confusion amongst EPs and perpetuate variation in the management of acute AF in the ED.8

The Cases

After a string of shifts in the ED, you realize that you saw 4 new patients with new onset AF over the past week. Considering that poor adherence to AF guidelines is linked to worse outcomes, you begin to wonder if you managed these patients appropriately.9,10 Specifically, you are unsure if you made the right decisions with regards to cardioversion and prescribing anticoagulants. You look up the most recent AF guidelines published by CAEP and CCS to review the cases. Below is the identifying data (ID), AF duration, and past medical history (PMH). Take a moment to ask yourself the following questions: 1) Would you cardiovert this patient?, and 2) Would you anticoagulate this patient?

| ID | AF duration | PMHx | |

| Case 1 | 60 y/o male | 16 hours | DM, HTN |

| Case 2 | 52 y/o male | 28 hours | None |

| Case 3 | 58 y/o female | 30 hours | DM, HTN |

| Case 4 | 57 y/o female | 5 hours | MHV |

Case 1

ID: 60 y/o male, AF duration: 16 hours, PMHx: DM, HTN

Management according to the guidelines

| CCS 2018 + 2020 | CAEP 2018 | |

| Safe to cardiovert? | NO | YES |

| Anticoagulation for 4 weeks? | YES | YES |

Using either the CHADS2 (CCS) or CHADS-65 (CAEP), this patient has a score of 2 (1 point for DM and 1 point for HTN). Given his high risk of stroke/TIA and onset of AF 16 hours ago, the CCS guidelines would recommend that he should not undergo cardioversion. On the other hand, CAEP states he could safely undergo cardioversion up until 24 hours. Both would recommend that this patient is prescribed anticoagulant therapy based on his CHADS-65 score.

Management in the ED:

In practice, you chatted with the patient and used shared decision making. Knowing the risks, he elected to undergo pharmacological cardioversion. He received a continuous intravenous infusion of Procainamide 1 g over 60 minutes, while you kept an eye out for hypotension and QRS prolongation. After 30 minutes, the patient successfully cardioverted back to sinus rhythm and was feeling better. You prescribed Rivaroxaban 20 mg PO daily and discharged him from the ED with outpatient follow-up with cardiology.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]Case 2

ID: 52 y/o M, AF duration: 28 hours, PMHx: none

Management according to the guidelines:

| CCS 2018 + 2020 | CAEP 2018 | |

| Safe to cardiovert? | YES | YES |

| Anticoagulation for 4 weeks? | YES | NO |

Using either the CHADS2 (CCS) or CHADS-65 (CAEP), this patient has a score of 0 and is therefore considered low risk for a stroke/TIA. Given his low risk and onset of symptoms 28 hours ago, both guidelines agree that he could safely undergo cardioversion. As for anticoagulation, CCS would recommend a prescription for 4 weeks, while CAEP would favor against it in this scenario.

Management in the ED:

You successfully performed electrical cardioversion, and the patient awoke from sedation, alert and ready for discharge. Given his low risk for stroke/TIA, you discussed the need for an OAC based on his values and lifestyle. He expressed that he works as a firefighter and plays contact ice hockey 2-3 nights a week. With that in mind, you both agreed that the medication cost and bleeding risks associated with an OAC are not worth the benefit. You discharged the patient without any medications to follow-up with cardiology.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]Case 3

ID: 58 year-old female, AF duration: 30 hours, PMHx: DM, HTN

| CCS 2018 + 2020 | CAEP 2018 | |

| Safe to cardiovert? | NO | NO |

| Anticoagulation for 4 weeks? | YES | YES |

Similar to Case 1, this patient has a CHADS2 score of 2 and a CHADS-65 score of 2 (1 point for DM and 1 point for HTN) and therefore she is considered high risk for a stroke/TIA. However, given the longer duration of symptoms, both the CCS and CAEP recommend against cardioversion, while supporting anticoagulation.

Management in the ED:

You opted to rate control the patient by IV Metoprolol. After lowering the heart rate, you immediately started her on Metoprolol 25 mg PO twice daily and Apixaban 5 mg PO twice daily with outpatient follow-up with internal medicine.

[bg_faq_end][bg_faq_start]Case 4

ID: 57 year-old female, AF duration: 5 hours, PMHx: MHV secondary to rheumatic heart disease

Management according to the guidelines:

| CCS 2018 + 2020 | CAEP 2018 | |

| Safe to cardiovert? | Not applicable* | Not applicable* |

| Anticoagulation for 4 weeks? | Not applicable* | Not applicable* |

Given the patients history of rheumatic heart disease and subsequent mechanical valve placement, this is a case of VAF, and she is inherently at high risk for stroke. Thus, the stroke risk tools and timing of cardioversion recommendations set out by the CCS and CAEP guidelines do not directly apply. Cardioversion should only be performed in patients with VAF if they have been therapeutically anticoagulated for 3 or more weeks or a transesophageal echo can be performed prior to cardioversion.

Management in the ED:

After confirming that the patient had not been compliant with her anticoagulation, you consulted cardiology and rate controlled the patient.

[bg_faq_end]Key Take Away Points

- CCS and CAEP have recently published guidelines for the management of emergency non-valvular AF that differ with respect to when and who should be cardioverted.

- Similarly, they differ in prescribing OACs to low-risk patients after cardioversion.

- The conflicting recommendations are based on low-quality evidence according to the GRADE standard, and thus, shared decision making with patients is crucial.

References

- 1.Andrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ Res. 2014;114(9):1453-1468. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303211

- 2.Andrade J, Aguilar M, Atzema C, et al. The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(12):1847-1948. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2020.09.001

- 3.Andrade J, Verma A, Mitchell L, et al. 2018 Focused Update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(11):1371-1392. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2018.08.026

- 4.Stiell IG, Scheuermeyer FX, Vadeboncoeur A, et al. CAEP Acute Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter Best Practices Checklist. CJEM. Published online April 3, 2018:334-342. doi:10.1017/cem.2018.26

- 5.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. Published online April 24, 2008:924-926. doi:10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.ad

- 6.Airaksinen KEJ, Grönberg T, Nuotio I, et al. Thromboembolic Complications After Cardioversion of Acute Atrial Fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Published online September 2013:1187-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.089

- 7.Nuotio I, Hartikainen JEK, Grönberg T, Biancari F, Airaksinen KEJ. Time to Cardioversion for Acute Atrial Fibrillation and Thromboembolic Complications. JAMA. Published online August 13, 2014:647. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3824

- 8.Stiell IG, Clement CM, Brison RJ, et al. Variation in Management of Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter Among Academic Hospital Emergency Departments. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Published online January 2011:13-21. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.07.005

- 9.Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, Tegegn HG. Poor outcomes associated with antithrombotic undertreatment in patients with atrial fibrillation attending Gondar University Hospital: a retrospective cohort study. Thrombosis J. Published online September 18, 2018. doi:10.1186/s12959-018-0177-1

- 10.Jortveit J, Pripp AH, Langørgen J, Halvorsen S. Poor adherence to guideline recommendations among patients with atrial fibrillation and acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Prev Cardiolog. Published online April 9, 2019:1373-1382. doi:10.1177/2047487319841940

This post was copedited by Samuel Wilson (@samwilson_95).