The Case

Your next patient in the acute zone of the ED is Mr. Liu, a 53-year old man presenting with one hour of acute onset atypical chest pain. He has several risk factors for coronary artery disease, including Type II diabetes, dyslipidemia and an 18 pack-year smoking history. He is hemodynamically stable. After two sets of normal high-sensitivity troponins and a normal EKG, you are confident that he is not suffering from an acute MI. You counsel him on diet and lifestyle modifications and ask him to follow up with his family doctor. However, you wonder if you should arrange further evaluation of his potential atherosclerotic disease with a stress test. What is the evidence for potential morbidity and/or mortality benefit of stress testing?

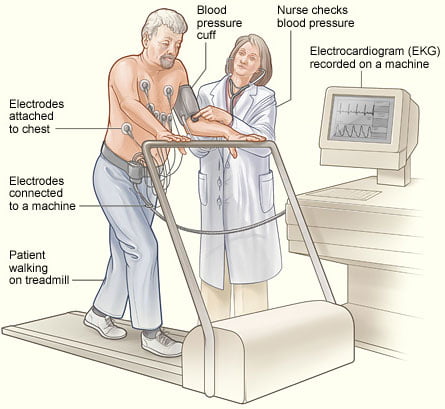

Introduction to stress testing

An exercise stress test commonly refers to a stress EKG, in which the patient exercises on a treadmill at progressive levels of intensity. Most commonly, the test is carried out in accordance with the Bruce protocol. The treadmill starts at 1.7 mph at a 10% incline and advances to 3.4 mph at a 14% incline over a period of 9 minutes.1 Throughout this time, the patient’s EKG tracing is monitored for inducible ischemic changes.

Clinical guidelines

In 2013, the American College of Cardiology Foundation reviewed appropriate indications for stress EKG testing. Importantly, they rated testing in asymptomatic patients as “rarely appropriate, except in intermediate- and high-risk individuals”. In this case, stress testing was rated as “may be appropriate”.2 For patients with symptoms representing stable ischemic heart disease or ischemic equivalents (including newly diagnosed heart failure, arrhythmias or syncope), stress testing was generally found to be “appropriate” or “may be appropriate”.2

The American College of Emergency Physicians released a clinical policy in June 2018 on the evaluation and management of NSTEMI. This policy provides more robust guidance on the potential utility of stress testing to reduce major cardiovascular events after a negative ED workup. They issued the following summarized recommendations for adult patients with suspected acute NSTEMI:

- In adult patients with no evidence of STEMI, the HEART score (History, EKG, Age, Risk Factors and Troponin) can be used as a clinical prediction tool for risk stratification. A score <3 is considered low, and predicts a 30-day major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) rate of 0-2% (Level B recommendation)

- Three potential patient scenarios are predictive of a low rate of 30-day MACE and may facilitate discharge from the ED:

- HEART scores 0-3 AND negative conventional troponin, OR

- a single undetectable high-sensitivity troponin, OR

- a non-ischemic EKG and negative serial high-sensitivity troponin at 0 and 2 hours (Level C recommendation)

- Further diagnostic testing, including stress testing, CT coronary angiography or myocardial perfusion imaging is not indicated to reduce 30-day MACE prior to discharge (Level B recommendations). However, follow up in 1-2 weeks should be arranged. If no follow-up is available, further testing or observation should be considered prior to discharge (Recommendation based on expert consensus).3

A review of the evidence on stress testing

A recent Emergency Medicine Cases podcast disputed the commonly cited 2% ACS miss rate after ED discharge.4 In the Pope et al. study, of the 10,689 patients presenting with undifferentiated chest pain, 889 patients had acute MI.5 Nineteen of the confirmed MI patients were mistakenly discharged. Therefore, of all patients presenting to the ED with undifferentiated chest pain, less than 0.2% were missed (whereas the 2% figure is derived from the 19 missed MIs of the 889 patients ultimately diagnosed with MI).4,5

This distinction becomes important when considering the potential consequences of ordering further investigation (and, downstream of this, invasive preventive treatment measures such as bypass surgery) when the patient is at low-risk of morbidity and mortality pre-intervention.

Morbidity and mortality benefit

Multiple large retrospective analyses have demonstrated no morbidity or mortality benefit of stress testing in the patient discharged after presenting with non-ACS chest pain, in addition to a low rate of development of MI post-discharge.

Foy et al. reviewed 693,212 ED visits with diagnoses of chest pain. Of the 421,774 patients included in the study, 0.11% of patients were hospitalized for MI at 7 days. Patients who didn’t undergo initial non-invasive testing (including stress testing) were no more likely to experience MI than those who did. Additionally, patients who underwent non-invasive testing were significantly more likely to undergo catheterization and revascularization, without an improvement in the risk of MI.6

In 2019, Natsui et al. completed a retrospective analysis of 24,459 patients presenting with chest pain in Southern California. Of the 7,988 patients discharged home with follow up, 0% died, 0.7% experienced acute MI and 0.3% underwent revascularization. Importantly, neither stress testing within 3 or 30 days was associated with improved 30-day MACE.7

False positive and negative rates

Stress tests may also have a high false-positive rate, leading to unnecessary further testing or additional procedures. In a cohort study of 1,243 patients referred for invasive coronary angiography, 51.6% ultimately had false-positive stress EKG results. False positivity was defined as ≤ 70% luminal narrowing or ≤ 50% narrowing of the left main artery on angiography. Factors independently associated with false positivity included: absent severe angina, atypical angina, female gender, non-smoking, absent diabetes and younger age.8

Conversely, stress tests may also miss clinically relevant outcomes including MIs. In two separate prospective observational studies of patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain, stress testing was negative in four patients from both study cohorts who ultimately had an MI post-discharge.9

Revascularization outcomes

The principle behind stress testing is to identify significant atherosclerotic lesions in patients who should have invasive procedures to revascularize the affected vessel. However, the ORBITA trial demonstrated that patients with significant single-vessel lesions (>70% stenosis) and stable angina did not fare better compared to placebo after invasive therapy.10

In this double-blind randomized controlled trial, 105 patients underwent drug-eluting stent placement, while 95 patients were in the placebo procedure arm. No significant difference was found in the primary endpoint of exercise time, peak oxygen uptake, change in angina symptoms post-procedure or patient-rated quality of life.

Consequently, for the patient presenting with chest pain whose testing is non-diagnostic for MI, stress EKG may not provide additional MACE benefit. False positives may lead to invasive procedures that do not improve long-term clinical outcomes, and patients with stable CAD and single-vessel significant atherosclerosis may not benefit further from revascularization.

Conclusion

You determine that Mr. Liu’s HEART score is 3, based on the combination of his history, age, and risk factors. This yields a MACE risk of 0.9-1.7% in the next six weeks. Based on the 2018 ACEP Guidelines, you determine that stress testing is not indicated and Mr. Liu may be safely discharged from hospital. However, you ensure that he has follow up with his family physician to optimize his heart health, and advice him to seek prompt medical attention should his symptoms return or worsen.

This post was copy-edited and uploaded by Kimberly Vella.

References

- 1.Akinpelu D, Yang E. Treadmill Stress Testing Technique. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1827089-technique#c2. Published November 21, 2018.

- 2.Wolk M, Bailey S, Doherty J, et al. ACCF/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2013 multimodality appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(4):380-406. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24355759.

- 3.Tomaszewski CA, Nestler D, Shah KH, et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Emergency Department Patients With Suspected Non–ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes. Annals of Emergency Medicine. November 2018:e65-e106. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.07.045

- 4.Helman A, Morgenstern J, Spiegel R. Cardiac Stress Testing After Negative Workup for MI. Emergency Medicine Cases. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/cardiac-stress-testing/. Published April 2019. Accessed August 10, 2019.

- 5.Pope J, Aufderheide T, Ruthazer R, et al. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(16):1163-1170. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10770981.

- 6.Foy AJ, Liu G, Davidson WR Jr, Sciamanna C, Leslie DL. Comparative Effectiveness of Diagnostic Testing Strategies in Emergency Department Patients With Chest Pain. JAMA Intern Med. March 2015:428. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7657

- 7.Natsui S, Sun BC, Shen E, et al. Evaluation of Outpatient Cardiac Stress Testing After Emergency Department Encounters for Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome. Annals of Emergency Medicine. August 2019:216-223. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.01.027

- 8.Park S, Sanchez D. The limited utility of cardiac stress testing in low-intermediate risk young adults presenting with chest pain. Circulation. 2016;134:A16436. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/circ.134.suppl_1.16436.

- 9.Morgernstern J. Stress tests part 3: stress test accuracy. First10 EM Blog. https://first10em.com/stress-test-accuracy/. Published March 13, 2019.

- 10.Al-Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi H-M, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. January 2018:31-40. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32714-9

Reviewing with the Staff

Chest pain is a common presentation in the emergency department. The clinician is challenged with the task of ruling out life-threatening diagnoses, with the most common focus being acute coronary syndrome. After thorough evaluation with history, physical examination, EKG and troponin, the majority of patients can be “ruled out” for myocardial infarction. The next question is what to do for those patients with negative tests. Historically, practice guidelines have recommended the use of short-term provocative testing, such as graded exercise stress testing, to further rule out underlying coronary disease in patients that have ruled out for acute coronary syndrome but not deemed to be very low risk.

The role of stress-testing has more recently come into question. Improvements in sensitivity of troponin test, in addition to clinical decision instruments such as the HEART score, have cut down the myocardial infarction miss rate. Further evidence, as discussed in this piece by Dr Tam, indicate that stress tests are both insensitive and nonspecific for underlying coronary disease. A small percentage of patients have accurate results. So surely, identifying those patients with actual significant atherosclerotic heart disease and undergoing subsequent angiography, angioplasty and stenting must be of benefit in the short- and long-term. Right? Not so fast. Foy et al (2015) showed that early stress-testing leads to early invasive tests without providing clinical benefit or reduced MI rates. Furthermore, a 2019 study by Natsui et al demonstrated no benefit to stress testing chest pain patients at 3 days or 30 days after an ED visit. Stress-tests for low-risk chest pain patients may soon be a thing of the past.