Cardiac arrest and hypotension are synonymous with emergency medicine. Over the years, point of care ultrasound (PoCUS) has become an extension of our stethoscope. The recently published consensus statement from the International Federation for Emergency Medicine (IFEM) aims to provide guidance for PoCUS use in these situations, and describes the Sonography in Hypotension and Cardiac Arrest (SHoC Consensus) protocols.1

The guidelines were developed based upon expert consensus formulated using three rounds of a modified Delphi approach. Recommendations were based on existing protocols and relevant literature. Disease incidence was also considered, and scanning is to be prioritized based on clinical probability.

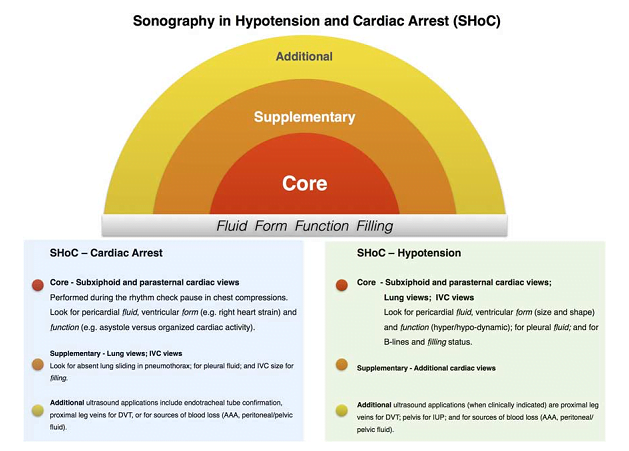

Ultimately, two protocols were developed, one for cardiac arrest and one for undifferentiated hypotension. Each protocol included core views, which are performed routinely for all patients; supplementary views, which are only performed on a case by case basis; and additional scans, which are performed when additional investigation is required. When interpreting each view, it is important to investigate each of the “4 Fs”: fluid, form, function, and filling. This approach is illustrated below using two cases.

Case 1 – Undifferentiated Hypotension

A 54-year-old female on chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer is brought in by paramedics with an altered level of consciousness. In your resuscitation room she is somnolent and can provide no meaningful history. She has a heart rate of 118, a blood pressure of 82/50 and a temperature of 37.7. There are no obvious findings on the physical exam. How would you further assess the patient?

Ultrasound findings

The undifferentiated hypotensive patient is a common and potentially challenging presentation. In addition to traditional history and physical exam findings, PoCUS can be used to assist in determining the correct type and cause of shock. There are various published algorithms in the literature, such as the RUSH2 and the ACES3 protocols, that each include several standard ultrasound windows. But which views yield the greatest impact in a timely fashion? The IFEM paper outlines an approach that is intuitive and efficient.

- Starting with the core views, you scan her heart from the subxiphoid and parasternal long axis windows. There is no pericardial effusion (fluid), chamber sizes appear normal (cardiac form), and the heart looks hyperdynamic in its contractions (function). If the images are not sufficient, supplementary cardiac views could be obtained, such as an apical 4 chamber or parasternal short axis scan.

- The next core scan interrogates the lungs. On our patient you do not see any pleural effusion (fluid) or B- lines to suggest pulmonary edema (cardiac filling).

- For your final core scan, you take a look at her IVC. It is small, collapsible and varies with respirations (filling).

- If there was clinical concern, additional scans to be considered would be abdominal views looking for peritoneal fluid or a AAA, or the legs in search of a proximal DVT.

Interpretation

In the context of this case, we have been presented with a picture of a specific clinical problem despite having a nonspecific presentation. These findings are consistent with non-cardiogenic shock: there’s nothing to suggest a massive PE or obstructive shock, the heart is filling and pumping effectively which rules out cardiogenic shock, and we can’t find a source of bleeding to account for hemorrhagic shock. In the context of a cancer patient with a poor immune response, they are likely septic and/or dehydrated. We can deal with this!

Case 2 – Cardiac Arrest

EMS rolls into your resuscitation room with a 48-year-old female who is receiving CPR. Over the commotion, the paramedic begins telling you the story. She was in the waiting room of a nearby walk-in clinic when she collapsed in front of several bystanders. She was pulseless and CPR was started immediately by clinic staff. An AED was retrieved and did not advise a shock. She has been in a PEA rhythm throughout and the paramedics have intubated and have been performing CPR for approximately 15 minutes.

You quickly run through your H’s and T’s of the ACLS algorithm, but nothing jumps out. Her blood sugar is 5.6 and there’s good air entry bilaterally. You wonder if ultrasound will be able to give you some clues.

Ultrasound findings

The IFEM cardiac arrest protocol is fairly similar to the one for undifferentiated hypotension.

- At the next pulse check you once again start with the core cardiac views. There is no cardiac contractility (function) and you don’t see a pericardial effusion (fluid). When you compare chamber sizes you see a massively dilated right ventricle (form).

- As CPR resumes you quickly perform a supplementary IVC scan, and you see a dilated vessel with no variation or compressibility (filling). Bilateral lung sliding was evident on supplementary lung views confirming ventilation and excluding tension pneumothorax.

Interpretation

At this point you have ruled out many correctable causes of cardiac arrest, including pericardial tamponade. A massive pulmonary embolism is at the top of your differential. These ultrasound findings suggest that thrombolysis should be considered. While the focus of this case was to demonstrate the utility of ultrasound during cardiac arrest, it is important to emphasize that CPR is always the priority in these patients. Ultrasound scans should never result in additional interruptions in resuscitation.

Summary of Guidelines for SHoC

Undifferentiated Hypotension Protocol:

- Core views

- Cardiac views (subxiphoid and parasternal long axis) to look for pericardial fluid, cardiac form and ventricular function

- Lung views to look for pleural fluid and B-lines for filling status

- IVC view to check filling status

- Supplementary views if needed

- Cardiac views (apical four chamber or parasternal short axis)

- Additional views if needed

- Abdominal views to look for peritoneal fluid or a AAA

- Proximal leg veins to look for DVT

- Endotracheal tube confirmation

Cardiac Arrest Protocol

- Core views

- Cardiac views to look for pericardial fluid, cardiac form and ventricular function

- Supplementary views if needed

- Lung views to look for lung sliding, and pleural fluid and B-lines for filling status

- IVC view to check filling status

- Additional views if needed

A large body of well-documented research forms the background leading to the development of these two protocols. They can help practitioners effectively diagnose some of the most difficult presentations in the ED!

Acknowledgements: Janelle Quintana, Kanisha Cruz-Kan

Institution: Emergency Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

This post was uploaded by Sean Nugent (@sfnugent)

References

Reviewing with Staff

So why do we need another ultrasound protocol in emergency medicine? RUSHing from the original FAST scan, playing the ACES, FOCUSing on the CAUSE and meeting our FATE, it may seem SHoCking that many of these scanning protocols are not based on disease incidence or data on their impact, but rather on expert opinion. The Sonography in Hypotension (SHoC) protocols were developed by an international group of critical care and emergency physicians, using a Delphi consensus process, based upon the actual incidence of sonographic pathology detected in previously published international prospective studies [Milne; Gaspari]. The protocols are formulated to help the clinician utilize ultrasound to confirm or exclude common causes, and guides them to consider core, supplementary and additional views, depending upon the likely cause specific to the case. Why would I take the time to scan the aorta of a 22 year old female with hypotension, when looking for pelvic free fluid might be more appropriate? Why would I not look for lung sliding, or B lines in a breathless shocked patient? Consideration of the shock category by addressing the “4 Fs” (fluid, form, function, and filling) will provide a sense of the best initial therapy and should help guide other investigations. Differentiating cardiogenic shock (a poorly contracting, enlarged heart, widespread lung B lines, and an engorged IVC) in an elderly hypotensive breathless patient, from sepsis (a vigorously contracting, normally sized or small heart, focal or no B lines, and an empty IVC) will change the initial resuscitation plan dramatically. Differentiating cardiac tamponade from tension pneumothorax in apparent obstructive shock or cardiac arrest will lead to dramatically differing interventions. SHoC guides the clinician towards the more likely positive findings found in hypotensive patients and during cardiac arrest, while providing flexibility to tailor other windows to the questions the clinician needs to answer. One side does not fit all. That is hardly SHoCing news. Prospective validation of ultrasound protocols is necessary, and I look forward to future analysis of the effectiveness of these protocols.

References

Scalea TM, Rodriguez A, Chiu WC, et al. Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST): results from an inter- national consensus conference. J Trauma 1999;46:466-72.

Labovitz AJ, Noble VE, Bierig M, Goldstein SA, Jones R, Kort S, Porter TR, Spencer KT, Tayal VS, Wei K. Focused cardiac ultrasound in the emergent setting: a consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and American College of Emergency Physicians. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2010 Dec 31;23(12):1225-30.

Hernandez C, Shuler K, Hannan H, Sonyika C, Likourezos A, Marshall J. C.A.U.S.E.: cardiac arrest ultra-sound exam – a better approach to managing patients in primary non-arrhythmogenic cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2008;76:198–206

Atkinson PR, McAuley DJ, Kendall RJ, et al. Abdominal and Cardiac Evaluation with Sonography in Shock (ACES): an approach by emergency physicians for the use of ultrasound in patients with undifferentiated hypotension. Emerg Med J 2009;26:87–91

Perera P, Mailhot T, Riley D, Mandavia D. The RUSH exam: Rapid Ultrasound in Shock in the evaluation of the critically lll. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2010;28:29 – 56

Jensen MB, Sloth E, Larsen KM, Schmidt MB: Transthoracic echocardiography for cardiopulmonary monitoring in intensive care. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2004, 21: 700-707.

Gaspari R, Weekes A, Adhikari S, Noble VE, Nomura JT, Theodoro D, Woo M, Atkinson P, Blehar D, Brown SM, Caffery T. Emergency department point-of-care ultrasound in out-of-hospital and in-ED cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016 Dec 31;109:33-9.

Milne J, Atkinson P, Lewis D, et al. (April 08, 2016) Sonography in Hypotension and Cardiac Arrest (SHoC): Rates of Abnormal Findings in Undifferentiated Hypotension and During Cardiac Arrest as a Basis for Consensus on a Hierarchical Point of Care Ultrasound Protocol. Cureus 8(4): e564. doi:10.7759/cureus.564