Editor’s Note: February 22 is National Human Trafficking Awareness Day. Today, CanadiEM is featuring a pair of posts with important takes on this issue.

A young woman presents to the emergency department with pelvic pain. She’s accompanied by her boyfriend who insists he come into the exam room and tries to provide the history for the patient, stating that she doesn’t remember things well. The patient makes poor eye contact and defers questions to the man. When you tell the patient that you will be doing a pelvic exam, the boyfriend insists the patient does not require a physical exam and that she just needs pain control. When you explain it is required, he only goes to the waiting room reluctantly. To assess safety, you ask the patient where she lives and if she can come and go as she wishes. She becomes quite nervous and says she has to leave to find her boyfriend. The pair then leave against medical advice.

Could this patient have been involved in human trafficking? What could you have done differently?

What is human trafficking?1

It is important for healthcare workers to recognize human trafficking. It involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to compel a person into commercial sex acts or labor or services against his or her will. Sex-trafficked patients specifically may endure forced confinement, physical violence, and forced use of drugs/alcohol. Consent is the missing element in sexual violence and trafficking. Every person is susceptible to exploitation and victimization, but in Canada, trafficking survivors are largely females under the age of 25. Trafficked individuals are resilient, strong people who often prefer to be referred to as “survivors” rather than “victims.”

Trafficked patients often do not seek help from police or authorities because of fear of their traffickers as well as isolation from friends and family, threats, history of committed crimes with their traffickers, and the fear that police will not believe them. Their traffickers may be intimate partners or family members and may manipulate survivors to believe they are not being trafficked.

Unfortunately, the majority of cases brought to court are withdrawn by complainants or stayed (paused or stopped) by courts. As care providers, physicians are one of only a few professions which interact with trafficking survivors when they are in captivity. It is estimated that 80% of trafficked individuals encounter a health care professional at some point during captivity.2 This provides healthcare workers with a unique opportunity to intervene and help a trafficking survivor break out of captivity, especially since on average it takes 5-7 attempts for a trafficked individual to leave their trafficker.

1. How do you recognize a trafficked patient?3

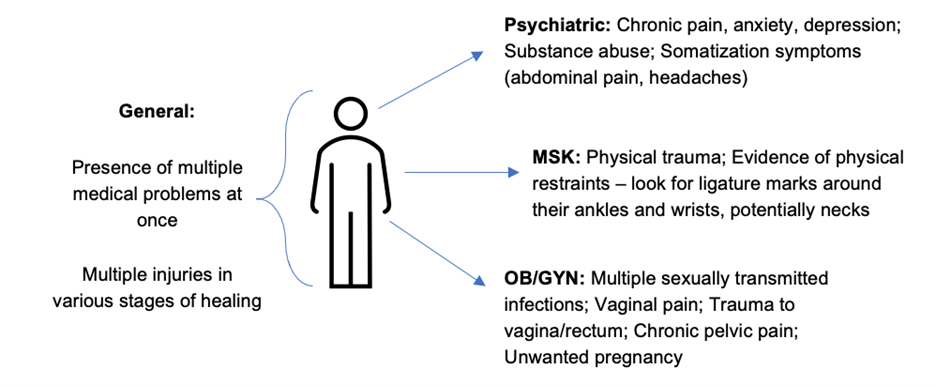

| Behavior | History | Physical |

| • Companion (male or female) who will not leave the patient and speaks for them. They might actively hunt down the patient if they get out of their sight • Nonchalant about significant medical illness/injury • Lack of license, passport or other belongings • Unsure of their surroundings – may mix up day/night • Emotional dysregulation • Difficulty making decisions Children/Adolescents* • Pregnancy/abortion at young age • History of running away from home/school/foster care placements • Hostile relationship to parents/caregivers • Angry/aggressive with staff | • Incompatibility between patient history and injury. • Delays between injury and seeking care • Frequent emergency room visits Many trafficked individuals have suffered major trauma. This may manifest as: • Post-traumatic stress disorder – recurrent thoughts/reliving events, detached, easily startled, hypervigilant, avoiding, dissociating • Memory disruption – inability to recall traumatic events • Trauma bonding – demonstrated loyalty and concern for trafficker, unwillingness to report/testify against. | • Suspicious tattoos/branding (burns/cuts; bar codes/crowns/initials in visible places) • Signs of drug/alcohol use • Inappropriate dress for work/weather |

*Note – In general, the age of consent is 16 throughout Canada, with exceptions for near-age peers. Children under 12 cannot consent to sex under any circumstance. No one under 18 can consent to sexual contact if it is involving a position of trust, a position of authority, or sex work.4

2. How does a physician properly intervene in the emergency department?6,7

Prepare properly to intervene… if you do at all.

Know your resources

- Most hospitals have specialized sexual assault and domestic violence support teams that can be called upon 24/7 from the ED.

Protect your patient

- Let your team know confidentially you are going to screen your patient for trafficking. Always be aware of who may be within earshot.

- Ensure that you can get the patient alone and in a safe location. Be aware that the simple act of separating them from their trafficker may put them in serious danger of punishment by their trafficker. If the patient resists being alone, take some time to think about whether it is the right decision.

Be respectful

- Meet the patient’s personal needs – offer food/drink, show them the rest rooms.

- Be careful of your language:

- Trafficked individuals often fear or distrust authority and are weary of disclosing personal information. Be respectful.

- Let the patient tell their story.

- Do not refer to their accompanying person as “trafficker” or “captor” – follow their language.

- Avoid passing judgment on the patients (“why are you staying with them?”)

- Only ask questions required to provide timely and appropriate care as gathering unnecessary details can hinder the interaction.

3. How do you screen for sex trafficked patients?6,7

- Begin with an open-ended question: “It is my practice to ask my patients about safety – is that alright?”

- Be aware there may be a trauma reaction if history taking triggers a memory of abuse.

- If the patient does not want to answer your questions, you should accept this decision. You can provide them with local resources, if they would like to take them.

- If the patient is open to it, you can ask screening questions adapted from the Vera Institute of Justice Screening Tool.This is time consuming so it may be helpful to enlist support from specialized hospital resources as discussed to ask these questions.

1. Are you allowed to take breaks where you work?

2. Have you ever felt that you could not leave where you work?

3. Does anyone at home or that you work with make you feel scared or unsafe?

4. Does anyone where you work ever trick, pressure or force you into doing something that you did not want to do?

5. Did anyone arrange your travel to Canada?

- You may also want to ask follow up questions if appropriate.

- Are you forced to work in your current job? Were you [or anyone you work with] ever injured or threatened for working slowly or for trying to leave? Does someone else control whether you can leave your house or not?

- Has anyone threatened your family?

- Do you have to ask permission to eat, sleep, use the bathroom, or go to the doctor?

- Do you owe your employer money? Is someone else in control of your money?

- Is someone else in control of your identification documents, passports, birth certificate, and other personal papers?

- Does anyone force you to have sexual intercourse for your work?

- It was found that trafficked patients most commonly answered yes to “Were you [or anyone you work with] ever beaten, hit, yelled at, raped, threatened or made to feel physical pain for working slowly or for trying to leave?” However, this question was not asked in isolation.

- Once the above is done, ask the patient if they have any questions for you.

4. How do you balance patient autonomy with the desire to intervene?6,7

- Above all, respect the patient’s choice. Allow the patient to decide how they would like to proceed.

- Emphasize confidentiality. Asking a patient if they want a referral gives them agency, which is important in trauma informed care.

- There are many barriers to a trafficking survivor’s self-identification including:

- Shame/guilt

- Fear of retaliation

- Fear of arrest

- Lack of transportation

- Fear of social services reporting

- Lack of understanding

- Drug/alcohol use

- No stable environment to return to from trafficking.

- Inform the patient that they can choose to contact a specialized treatment program or the police. Many survivors do not want to contact police and that should be respected.

- Note that a provider cannot force a person to report a crime nor can they report it themselves (normal confidentiality exceptions would apply including child abuse and gunshot wounds). This can be frustrating to a well-intentioned physician but a survivor or their family may be at risk if a crime is reported. Law enforcement should only be engaged with your patient’s consent.

- However, if there is immediate danger to you, staff or the patient (with consent), call 911 or your local police service.

Remember, our role as physicians is to support the health and safety of our patients. Respecting their dignity and choices while offering them care and support is essential to helping a trafficked patient.

Imagine a different situation as the case presented, this time with the staff having been trained in what to look for in a trafficked survivor…

When the woman presents to triage, the nurse notes a sixth visit for pelvic pain. Her suspicions are raised when the accompanying male answers questions for the patient and holds her health card. The nurse relays her suspicions to you, the physician. You meet the couple, and early on explain the patient will be seen alone for a required sensitive exam. You refresh your memory on the information for the specialized hospital support team and community resources for referral. You let your nurse know confidentially that you are going to try to screen the patient for trafficking and emphasize how a dangerous situation like this requires extreme discretion.

You start the history and once she seems relaxed, you ensure that you are in a safe and private space. You inform her that you always ask patients some questions about safety. She looks uncomfortable but mumbles, “… fine.” The patient tells you she works as a cleaner and lives with a few other girls. She states she has been with her current partner a few months and insists he treats her well. You respect her choice not to answer any further and go on to complete the exam with a chaperone present. After the exam she tells you she can’t keep her boyfriend waiting too long. You ask the patient if there is anything else, she would like to talk about and she says no. You explain to her that the Emergency Department is a safe place and if she ever finds herself in need of assistance that she is welcome to return. You offer her a discrete card with information on local resources, allowing her time to look at it in the privacy of her room. She leaves.

[bg_faq_start]Patient & Provider Resources (click to enlarge)

Hospitals have in-hospital referral teams available to support victims and emergency physicians.

- They can often be found by googling “sexual assault domestic violence [name of hospital]” and are available 24/7 to consult to the emergency department.

A list of sexual assault/domestic violence treatment centres in Ontario is searchable here:

- https://www.sadvtreatmentcentres.ca/find-a-centre/

Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline

- Canada has a dedicated, confidential, 24/7 human trafficking hotline. Toll-free: 1-833-900-1010. The hotline is for: victims seeking help; people with a tip to report a potential case; members of the public wanting to learn more about the subject

Resources on sex trafficking – https://healtrafficking.org/ and labor trafficking https://www.canadiancentretoendhumantrafficking.ca/labour-trafficking/

[bg_faq_end]Acknowledgements: With support from Nicky Carswell (SASCW), Krystal Snider (YWCA), Nicole Biros (Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund), Dr. Julianna Deutscher (Resident Physician), Dr. Hanni Stoklosa (HEAL Trafficking), Dr. Kari Sampsel (Emergency Physician and the Medical Director of the Sexual Assault and Partner Abuse Care Program at the Ottawa Hospital)

This post was copyedited by Parnian Pardis and edited by Daniel Ting.

References

- 1.Cotter A. Trafficking in persons in Canada, 2018. Statistics Canada, Government of Canada . Published 2018. Accessed October 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2020001/article/00006-eng.htm

- 2.Andrews K. Physicians Against Sex Trafficking . Federation of Medical Women of Canada. Published 2019. Accessed August 2020. https://fmwc.ca/physicians-against-sex-trafficking/

- 3.National Human Trafficking Resource Center. What to Look for in a Healthcare Setting. National Human Trafficking Hotline. Published 2018. Accessed October 2020. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/resources/what-look-healthcare-setting

- 4.Government of Canada Dof J. Age of Consent to Sexual Activity. Department of Justice. Government of Canada. Published 2017. Accessed July 2020. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/other-autre/clp/faq.html

- 5.The Vera Institute. Screening for Human Trafficking . Vera Institute of Justice. Published 2014. Accessed June 2020. https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/human-trafficking-identification-tool-and-user-guidelines.pdf

- 6.Macias-Konstantopoulos W, Owens J. Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool and Guide. Administration for Children & Families. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Published 2018. Accessed July 2020. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/otip/adult_human_trafficking_screening_tool_and_guide.pdf

- 7.Mumma B, Scofield M, Mendoza L, Toofan Y, Youngyunpipatkul J, Hernandez B. Screening for Victims of Sex Trafficking in the Emergency Department: A Pilot Program. WestJEM. Published online June 1, 2017:616-620. doi:10.5811/westjem.2017.2.31924

Reviewing with the Staff

Human trafficking is not an uncommon phenomenon in Canada – and these patients will be seeking their medical care in the Emergency Department. Many people assume that survivors of human trafficking are people from other parts of the world who have immigrated to Canada – this is not the case the vast majority of the time, particularly those involved in sexual exploitation. Most survivors are fellow Canadians and are recruited and trapped into this modern-day slavery through coercion. Survivors of human trafficking are usually stripped of all their identifying documentation and money, and risk their lives escaping their captors to seek help. For those reasons – survivors often seek help in the ED – as we are always open and always capable of taking care of people, regardless of their paperwork status. We need to be mindful of how survivors can present and create a safe place to meet their healthcare needs.