A 32 year-old female presents to your Emergency Department one afternoon with the presenting complaint of altered level of consciousness. On examination you find her to be agitated and confused, as well as tachycardic and febrile at 39.5o C. Collateral history from EMS is negative for any substance misuse. When reviewing her chart, you find that she has recently been started on Risperidone for her schizoaffective disorder…

Fever vs Hyperthermia

It is important to note that the terms fever and hyperthermia are not synonymous. The hypothalamus is responsible for regulating body temperature, maintaining it at its normal set point (37.5 degrees C).1 In fever, this set point is increased, and the body subsequently increases heat production to reach the new set point. In hyperthermia however, the setting of the hypothalamus does not change. Instead, body temperature is increased by one of two mechanisms: exogenous heat exposure, or endogenous heat production.1 This results in body temperature increasing in an uncontrolled manner, at a rate too rapid to be compensated for by our body’s natural ability to lose heat. Aside from their different etiologies, it is important to differentiate between these two as hyperthermia can require different interventions than fever and can be rapidly fatal.

There are many types of hyperthermic syndromes in medicine, some of the more common causes listed in Table 1.

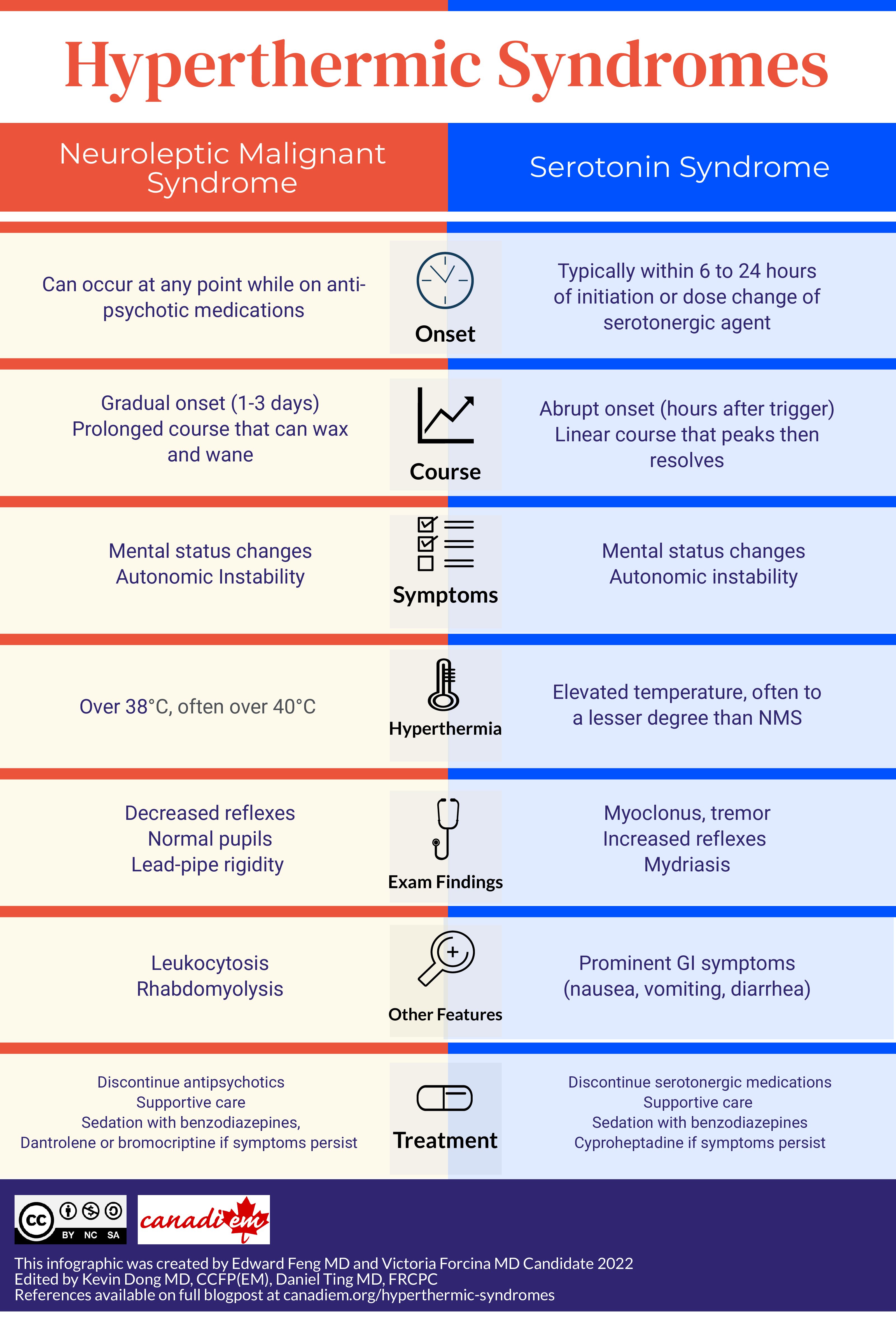

In this post, we will be talking about two of the can’t miss causes of hyperthermia commonly seen in the psychiatric patient: neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome.

| Table 1. Common causes of Hyperthermia1 |

| • Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome • Serotonin Syndrome • Malignant hyperthermia • Parkinsonism hyperpyrexia syndrome • Substance withdrawal (e.g. Baclofen, alcohol, opiates, benzodiazepines) • Acute overdose (e.g. anticholinergic syndrome, sympathomimetics, lithium, ASA) • Pheochromocytoma • Heat stroke • Sepsis • Encephalitis, meningitis • Thyrotoxicosis (thyroid storm) |

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) occurs in 0.02-3% of patients taking antipsychotic medications.2 Most commonly, NMS is seen with first generation antipsychotics such as Haloperidol, but can occur in any class of antipsychotics.2 Symptom onset typically occurs during the first two weeks of initiation of antipsychotic therapy, although it can occur at any point after initial treatment. NMS is known for its four classic clinical features remembered by the mnemonic HARM: hyperthermia, autonomic instability, rigidity, and mental status change.2 The diagnosis should always be considered in patients taking antipsychotic presenting with 2 or more of these symptoms. These four symptoms tend to develop gradually over 1-3 days with a prolonged disease course that can wax and wane.1

- Hyperthermia

- The vast majority of patients with NMS have temperatures over 38C, however temperatures greater than 40C are common.

- Autonomic Instability

- Frequently characterized by tachycardia, hypertension, tachypnea and diaphoresis.

- Rigidity

- Muscular rigidity seen in NMS is both generalized and frequently severe. Increased tone can be seen, with “lead-pipe rigidity.” Tremor is also frequently present, with a minority of patients experiencing dystonia, trismus, chorea, and other dyskinesias.

- Mental status change

- Although listed last in the mnemonic, this is the initial presenting symptom in the vast majority of patients with NMS. In this context, the mental status change is commonly agitated delirium with confusion, but can also have catatonic signs and mutism.

If NMS is suspected in a patient, the patient’s antipsychotic medication should be discontinued, and vitals should be monitored closely; if clinical symptoms are severe, admission to ICU may be required.3 If discontinuation of the antipsychotic agent does not provide clinical improvement, benzodiazepines, dantrolene, bromocriptine or amantidine should be considered.3 Electroconvulsive therapy can also be considered if residual symptoms persist following resolution of other symptoms.4

Serotonin Syndrome

As the name implies, serotonin syndrome (SS) occurs when there is increased serotonergic activity in the CNS. This usually occurs in the context of four situations: ingestion of serotonergic medications (especially combinations of these medications), drug interactions between serotonergic medications and MAOIs or linezolid, intentional overdose of serotonergic medications, and serotonergic drugs of abuse such as MDMA.1 Similar to NMS, SS can also be life threatening. However unlike NMS, its onset tends to be much more predictable, with the majority of serotonin syndrome present within 6 to 24 hours after a change or initiation of drug.5 Serotonin syndrome symptoms can be remembered with the acronym MAN: mental status changes, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular abnormalities.6

- Mental Status Changes

- As opposed to NMS which presents primarily with agitated delirium with confusion, SS can present with this as well as anxiety, restlessness, and disorientation.

- Autonomic Hyperactivity

- Autonomic manifestations typically include hyperthermia, diaphoresis, tachycardia, hypertension, vomiting and diarrhea. Some differentiating features are that SS tends to have a milder degree of hyperthermia compared to NMS, and SS is more likely to be associated with GI symptoms such as diarrhea and vomiting.

- Neuromuscular abnormalities

- Neuromuscular abnormalities represent the largest clinical difference between NMS and SS. Myoclonus, hyperreflexia, tremor, and bilateral Babinski sign are all seen in SS, most prominently in the lower extremities.

SS is a clinical diagnosis made using the Hunter Criteria, history and physical examination.5 The Hunter criteria specifies that a patient must have taken a serotonergic agent and meet one of the conditions:

- Spontaneous clonus

- Inducible clonus + agitation or diaphoresis

- Ocular clonus + agitation or diaphoresis

- Ocular clonus or inducible clonus + hypertonia + temperature above 38

- Tremor + hyperreflexia

Treatment of SS involves immediate discontinuation of all serotonergic agents, supportive care (maintaining oxygen saturations above 94%, IV fluids, continuous cardiac monitoring, correction of vitals), sedation with benzodiazepines, and possible administration of serotonin antagonists such as cyproheptadine.6

Takeaways:

Both serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome are key diagnoses to be considered in the differential for the hyperthermic patient. Look for key clues in the history such as medications taken, recent dose changes, and onset of symptoms. An easy way to remember the clinical features for the two syndromes are the mnemonics HARM and MAN. Once diagnosed, treatment revolves around discontinuation of the offending medications and supportive care.

On further examination you also notice generalized “lead-pipe rigidity” in the patient. You make the diagnosis of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and ensure that no further doses of anti-psychotics are given; instead, you treat her with fluid resuscitation and continue to monitor her. You treat her agitation with benzodiazepines, but her symptoms persist and eventually admission to hospital is needed.

This post was copy-edited by Casey Jones (@CaseyMAJones) and was edited by Daniel Ting (@tingdan).

References:

- 1.Caroff S, Watson C, Rosenberg H. Drug-induced Hyperthermic Syndromes in Psychiatry. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2021;19(1):1-11. doi:10.9758/cpn.2021.19.1.1

- 2.Ahuja N, Cole AJ. Hyperthermia syndromes in psychiatry. Adv psychiatr treat. Published online May 2009:181-191. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.107.005090

- 3.Levine M, LoVecchio F. Antipsychotics. In: Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine. McGraw-Hill Education; 2015:1457-1460.

- 4.Strawn JR MD, Keck PE Jr,MD, Caroff SN MD. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. AJP. Published online June 2007:870-876. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.870

- 5.LoVecchio F, Mattison E. Atypical Antidepressants, Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, and Serotonin Syndrome. In: Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine. ; 2015:1448-1453.

- 6.Boyer EW, Shannon M. The Serotonin Syndrome. N Engl J Med. Published online March 17, 2005:1112-1120. doi:10.1056/nejmra041867

Reviewing with the Staff

The \"Hot and Bothered\" patient in the Emergency Department is a dangerous presentation with a broad differential diagnosis. Remembering to check for neuromuscular abnormalities (i.e., clonus in serotonin syndrome or rigidity in neuroleptic malignant syndrome) as a routine part of the physical exam of these undifferentiated patients can be the key in making this rare diagnosis.