You are working a busy shift in the emergency department and are trying to quickly disposition patients. As the shift progresses and your feet hurt, you wonder why your work space is far removed from the patient care area, and different walls have bins that contain order sets, handover notes, and referral forms. Moreover, the route to sending the tube to the lab crosses too close to the dirty utility room. You think to yourself, “I wonder if they consulted a healthcare worker when designing this?”

Welcome to another HiQuiPs post where we discuss the important topic of human-centred design in healthcare. Human-centred design thinking is being leveraged more and more frequently within the healthcare context to develop services, physical spaces and processes that meet the needs of healthcare providers and patients, as well as improve patient safety.1,2 The International Organization of Standards defines human-centered design as:3

‘…an approach to interactive systems development that aims to make systems usable and useful by focusing on the users, their needs and requirements, and by applying human factors/ergonomics, usability knowledge, and techniques. This approach enhances effectiveness and efficiency, improves human well-being, user satisfaction, accessibility, and sustainability; and counteracts possible adverse effects of use on human health, safety, and performance.’3

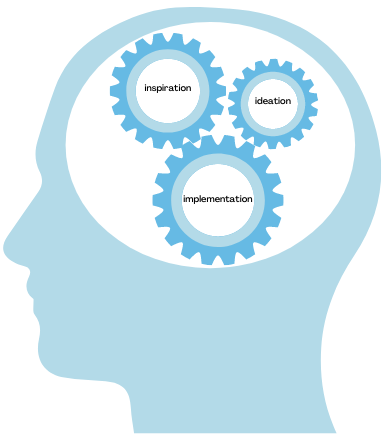

Human-Centered Design Phases

The complex and adaptive nature of the Emergency Department (ED) requires space, process and service design that is contextualized to the environment. A “one-size fits all” design approach is unlikely to yield to resolution of the problems each unique ED is facing. The human-centered design approach can solve practical issues and problems faced in EDs. The three phases of human-centered design include:4

- Inspiration: empathize with the end-users (e.g. patients, nurses, physicians, family members) and determine their needs / wants (e.g. through observations and interviews).

- Ideation: identify ideas and share them through prototypes.

- Implementation: continuously test your prototypes with the end users, gather their feedback and incorporate their feedback until you have developed a solution that meets their needs.

The human-centred design process is nonlinear and requires flexibility and iteration to refine ideas into acceptable solutions.1,4

Human-Centered Design Examples

A Practical Example of Poor Design

You have likely seen instances of poor human-centred design within your everyday life. For instance, how many times have you pulled a door handle to try and open a door and then quickly realize it is actually push door? In this situation, the function of the door handle is not obvious. The door handle design should quickly communicate its function to the user. For example, a door with flat metal plate would imply that it is a push door – it wouldn’t even allow the option to try and pull it open.5

Leveraging Human-Centered Design in Healthcare

- Kaiser Permanente (KP) worked with IDEO to improve nurse handover at shift change . Through the human-centered design process, KP worked with patients and providers to design the “Nurse Knowledge Exchange”– a standardized bedside handover process for nurses to quickly and reliably transfer information with patient involvement. KP has also used the human-centered design process to uncover gaps in care. For example, while observing nurses for a medication safety project, it was uncovered that interruptions and distractions may often led to medication errors.6

- Design labs can also be found embedded within healthcare organizations now.2 For example, Open Lab and Healthcare Human Factors (both partners of University Health Network) provide a space where patients, healthcare providers and design thinkers can collaborate to develop solutions for healthcare challenges.7,8 For example, with patients and providers, Open Labs co-designed “Patient Orientated Discharge Summaries (PODs)” to communicate key information with patients before they are discharged from hospital.9

So Why is This Important to Know?

Reflecting on your own workflow, are there elements or processes that can be optimized to better suite it? Are there opportunities where you can get involved when your work spaces, processes and services are being designed or updated? Are there opportunities to solve current design issues to get involved in? Your opinion as a front line worker is essential.

A common response to poorly designed workflows are workarounds – “informal temporary practices for handling exceptions to normal procedures or workflow”.10 From the vignette, this would include: you start carrying order sets and referral forms around with you so you don’t have to walk around collecting them when needed.

Workarounds can have unintentional consequence that compromise safety. For example, a nurse working at an organization using barcode medication administration scans a copy of the patient’s barcode (deviation from best practice) instead of the barcode on the wristband the patient is wearing. Failure to comply to the scanning best practices for medication administration can contribute to a medication errors reaching and harming patients. It is important to identify workarounds, understand why they are occurring and optimize design in a human-centered approach to address them.

Now that you know more about human-centered design process, you bring it up at your next business meeting. A small group is put together to think through the different ED processes suffering from inefficiencies, barriers and workarounds. Your feet start to feel better already!

Key Points

- Human-centered design requires you to understand the people you are designing for.

- The human-centered design process may require you to “go back to the drawing board” multiple times in order to develop a solution that the end user will adopt.

- Healthcare organizations are already using human-centered design.

Copy editor: Laura Pozzobon

Senior editor: Ahmed Taher

References

- 1.Altman M, Huang T, Breland J. Design Thinking in Health Care. 2018. 15:http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180128external icon.

- 2.Criscitelli T, Goodwin W. Applying human‐centered design thinking to enhance safety in the OR. 105. 4(412):10.1016/j.aorn.2017.02.004.

- 3.International Organization for Standardization. Ergonomics of human-system interaction — Part 210: Human-centred design for interactive systems (ISO 9241-210:2019). https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9241:-210:ed-1:v1:en.

- 4.IDEO. The field guide to human-centered design. . Published 2015. https://d1r3w4d5z5a88i.cloudfront.net/assets/guide/Field%20Guide%20to%20Human-Centered%20Design_IDEOorg_English-0f60d33bce6b870e7d80f9cc1642c8e7.pdf

- 5.Norman D. The Design of Everyday Things. Revised and Expanded Edition. Basic Books; 2013.

- 6.McCreary L. Kaiser Permanente’s Innovation on the Front Lines. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2010/09/kaiser-permanentes-innovation-on-the-front-lines

- 7.Open Lab. What is Open Lab? http://uhnopenlab.ca

- 8.Healthcare Human Factors. A future where was can all thrive. https://humanfactors.ca

- 9.Huynh T, Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Abrams H, Madho C. Patient oriented discharge summary (PODS). http://uhnopenlab.ca/project/pods/

- 10.Kobayahi M, Fussell S, Xiao Y, Seagull F. CHI ’05 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems.:1561-1564.