The Case

A 17-year-old female was transported to the Emergency Department (ED) by helicopter after a high speed, single vehicle motor vehicle collision. She was found unrestrained by paramedics, with an initial Glasgow Coma Scale of 14, but during extrication she became more agitated and confused. Subsequently she complained of dyspnea and became hypotensive. She was intubated prior to transport for her deteriorating mental status. The patient received 3 litres of crystalloid along with bolus doses of phenylephrine through an interosseous line to maintain adequate blood pressure.

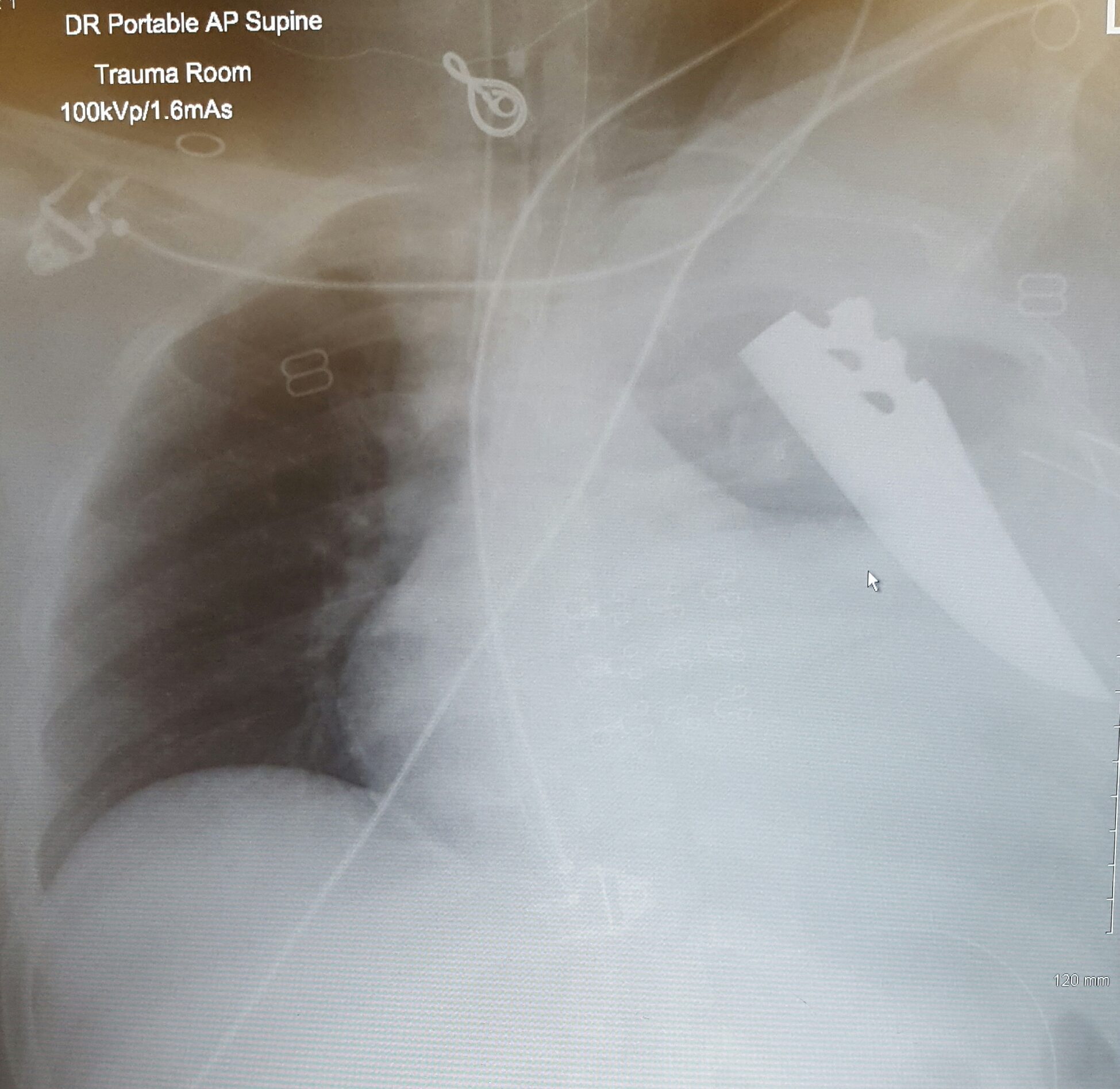

In the ED she was found to be stable on continuous positive pressure ventilation with normal airway pressures. The physical exam was notable for decreased air entry on the left side, and a 4 cm, uneven laceration on the left upper chest, overlying the third intercostal space in the mid-clavicular line. The wound was oozing scant dark blood, and inspection revealed extension into the subcutaneous fat. It was covered with an occlusive dressing. Bedside ultrasound was negative for free abdominal fluid or pericardial effusion, but revealed a left hemopneumothorax and poor cardiac wall motion. A finger thoracostomy was performed on the left chest allowing for the decompression of air from the pleural space, followed by placement of a 36- French chest tube, which drained 100 mL of dark red blood. There was resistance to advancement of the chest tube, so it was sutured in place at 10 cm. The patient was given two units of O-negative blood, while a portable chest radiograph (CXR) was taken.

The patient was log-rolled to expose her back, but no injuries or foreign bodies were visible posteriorly. Immediately after the log roll, the patient became hypotensive and pulseless. One cycle of chest compressions were initiated and the patient quickly had a return of spontaneous circulation.

Preparations were made for a resuscitative thoracotomy, and a thoracic surgeon was consulted while a right sided chest tube was placed and a massive transfusion protocol was initiated. The decision was made to take the patient to the operating room (OR), where the thoracic surgeon performed a left thoracotomy, extracted the blade and removed the lingula of the left lung for hemostasis.

The patient survived surgery. After a short recovery in the intensive care unit, she was extubated and sent to the pediatric clinical teaching unit for observation and recovery. It is still unclear how the knife ended up in her chest.

Discussion

Although penetrating trauma to the chest is common, retention of the blade is unique. There are no established guidelines for dealing with this type of injury, and practice differs between centres.1 Up to 18% of patients who have a retained weapon from a penetrating injury will have a delayed presentation, which is associated with increased adverse outcomes.2,3 Penetrating trauma to the chest has an overall fatality rate of 47%.4 Interestingly, when the weapon is retained in the patient’s body, fatality was only 7%, likely due to the tamponading effect of the weapon.1 Hemodynamic instability on arrival to the ED is rare, except in anterior thorax injuries resulting in a massive hemothorax or cardiac tamponade.

As in this case, a history of penetrating trauma is not always clear. When inspecting any wounds on the thorax, one should maintain a high index of suspicion for a penetrating injury, or a retained blade if the wound is deep or the entire weapon has not been recovered. Unstable patients should proceed directly to the OR for extraction and exploratory surgery.1,5 In stable patients, the wound can be probed with a sterile gloved finger, or a long cotton swab to determine the depth, and extension into the thoracic cavity, although wound appearance alone shouldn’t change management.6 The potential for accidental injury to the health care worker from the sharp edges also exists, and care must be taken when probing a wound, placing a chest tube, or performing CPR.

Ultrasound should be used to look at the heart for the presence of pericardial fluid, and if positive, the patient should proceed to the OR. A CXR should be obtained to look for air or fluid in the intrathoracic cavity. If neither is present, the CXR can be repeated after 1 hour. Up to 3% of patients will have a new finding on the second CXR that warrants intervention.6 As in this case, a knife blade may break off from the handle. Therefore, imaging also plays an important role in locating a retained weapon.7,8 CXR remains a sensitive modality for detecting radiopaque foreign bodies, and equivocal studies warrant CT imaging.

Due to a tamponading effect of the weapon, it is important not to manipulate or extract the knife until life threatening injuries have been excluded. In patients where imaging shows only a superficial injury, there was a 5% post-extraction bleeding risk. Therefore, extraction of an obvious knife, in the absence of life-threatening injuries can occur safely in the ED.1,2

This post was uploaded by Sean Nugent (@sfnugent)

References

Reviewing with Staff

This case really highlights the need to maintain an open mind to the potential for penetrating injury in an unstable, undifferentiated trauma patient. The history here suggested only blunt trauma; the only insinuation of penetrating injury was the (unimpressive) anterior thoracic laceration. We were all shocked when faced with this patient’s portable chest radiograph – but we should not have been.

The failure in this case to consider penetrating trauma is likely due to a combination of cognitive biases that we need to be vigilant for, including:

1. Confirmation bias – looking for evidence to support a pre-conceived judgment, rather than looking for information to prove oneself wrong

2. Premature closure – similar to confirmation bias, but more “jumping to a conclusion”

These biases can be combatted by rigorously gathering additional information and developing a broad differential diagnosis, as well as by identifying and investigating any “red flag” symptoms (i.e. anterior chest laceration). Think back to the last time you saw a motor vehicle collision result in an anterior thoracic laceration – contusion sure, but laceration, odd.