During your Emergency Medicine (EM) rotation, you’ve encountered numerous lacerations and have honed your suturing skills. Following the primary closure of your most recent laceration, your supervising physician has requested that you apply an appropriate dressing and provide wound care instructions, as the nursing staff are preoccupied with attending to other patients.

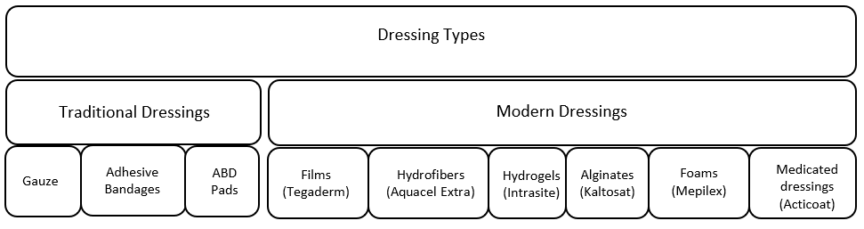

You look at the Wound Product Information Sheet and are surprised by the variety of dressings available in the Emergency Department (ED). What are the differences between these dressings, and how should they be applied to various wounds? How do you determine the appropriate dressing choice?

Figure 1: Vancouver General Hospital (VGH) Wound Product Information Sheet *Image taken by author, © 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY 4.0.

Dressings are not explicitly taught in medical school and are generally learned informally. This post aims to explain the differences between basic dressing types and introduce a framework for thinking about dressing choices based on wound characteristics. We will use a few case studies to illustrate and will provide evidence-based recommendations when applicable.

Clinical Question

What is the best dressing choice for common wound presentations in the ED?

Objectives

- Provide an overview of common dressings available in the ED

- Explain dressing choices for common ED wound presentations

- To answer common questions around wound management

Overview of common ED dressings

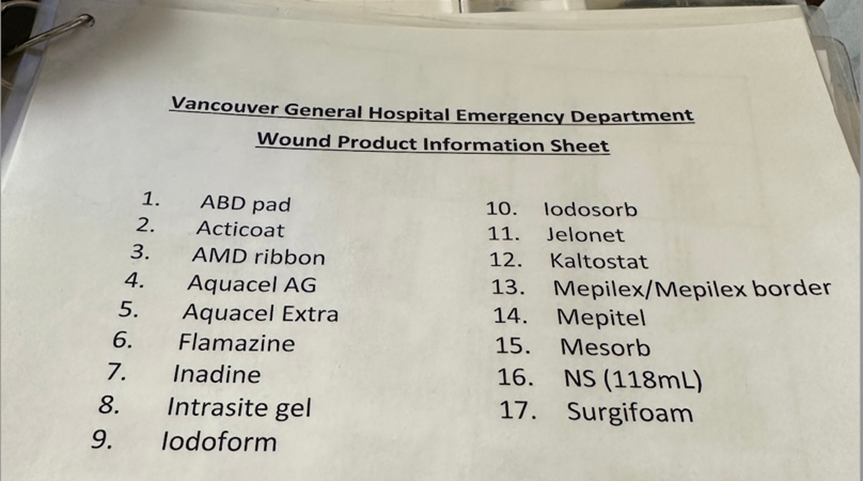

Conceptually, dressings can be divided into traditional and modern types.

- Traditional dressings, such as gauze, bandages, and sterile cotton, cover the wound, keep it dry, and are less costly. Generally, traditional dressings are suitable for clean and dry wounds.1

- Modern dressings can maintain moisture, possess antibacterial properties, and maintain a relatively constant temperature, which promotes wound healing. They tend to be more expensive and are commonly used for more complex wounds.2 The table below summarizes common modern dressings and highlights some of their advantages.3

Table 1: Overview of modern dressings and their indications *All product images are taken by the author. © 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY 4.0.

Case 1: Uncomplicated hand laceration after primary closure

Figure 2: Primary closure of an uncomplicated laceration. *Image taken by author after verbal consent from the patient. © 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY 4.0.

An otherwise healthy 24-year-old male cuts his hand while opening a can of corn and presents to the ED. After primary closure with non-absorbable sutures, your staff asks you what dressing would be appropriate and what discharge instructions you would give the patient?

Answer:

This is likely the most common dressing-related question you will encounter. In fact, there is no strong evidence to suggest that dressings aid in the healing of lacerations after primary closure.

In a 2016 Cochrane review, Dumville et al. examined 29 trials involving 5,718 participants to assess the role of dressings and their effectiveness in reducing the risk of postoperative surgical site infections after primary closure. They found no evidence that dressings reduce the risk of wound infections. Furthermore, they concluded that no specific wound dressing is superior to a basic contact dressing in terms of improving scarring, reducing pain, or being more acceptable to patients.4

A 2015 systematic review by Toon et al., which included 280 participants with clean and clean-contaminated surgical wounds, found no difference in the 30-day rate of infection, wound dehiscence, or adverse events between early dressing removal (<48 hours) and delayed dressing removal (>48 hours).5

Bottom Line:

Although we did not find any systematic reviews specifically in the ED setting, the evidence from post-operative patients does not support the use of dressings for sutured wounds to prevent infection. Wounds in the ED generally require more debridement and irrigation; however, the risk of infection is still very low.6 In this case, we would opt for a low-cost traditional dressing, such as simple gauze or bandage, to cover the wound for 1-2 days to absorb any minor bleeding from the site. Tegaderm films can also be used which allows patients to shower immediately after the injury in the case of larger wounds on the leg or torso. There is no need for more expensive dressings for the purpose of wound healing.

Frequently Asked Questions:

1. Can I shower or clean the wound?

Heal et al. randomized 857 patients with minor skin excisions in the primary care setting to either remove the dressing within 12 hours and wash the wound or keep the wound dry for 48 hours. They found no significant differences in surgical site infections (wet = 8.4%, dry = 8.9%; P=0.78). Recommending that patients clean minor wounds with soap and water is reasonable, provided they are careful not to remove sutures or staples.7

2. Do I need to apply topical antibiotic ointments such as polysporin?

Del Beccaro and Cummings, in a meta-analysis of 7 trials involving 1,734 subjects, concluded that there is no benefit to using prophylactic antibiotics for non-bite wounds in the ED to prevent wound infections (Odds ratio = 1.16 for antibiotic group).6 This study involved the use of intramuscular and oral antibiotics administered in the ED. The evidence does not support a role for prophylactic antibiotics in the context of most simple, non-bite wounds after primary closure, and it is reasonable to extrapolate these results to include topical antibiotics.

3. How do I minimize the scar appearance?

Scott et al., in a scoping review of 25 studies involving 1,515 participants, concluded that massaging the scar has qualitative benefits in reducing pain and improving scar characteristics after the wound edges have healed. However, they highlighted the difficulty of objectively measuring scar appearance, noting that studies did not use uniform criteria.8 Evidence also supports the use of sunscreen to prevent sunburns during the healing phase of a scar, which may last up to 18 months after injury.9 Silicone gel sheets have been shown to be effective for wounds at a higher risk of hypertrophic scar formation, as demonstrated in a 2020 systematic review by Tran et al.10 Overall, massaging the scar tissue for 2-3 weeks and applying sunscreen are low-cost and easy-to-follow recommendations supported by qualitative literature. Pathological scars, such as hypertrophic and keloid scars, may require more advanced dressings applied for longer periods and consideration for revision surgery.

Case 2: Superficial partial-thickness burns

Figure 3: A superficial partial-thickness burn prior to any treatment. Image taken from Wikimedia Commons. © 2008. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED [8].

A 30-year-old female presents to the ED with a burn injury after contact with flames from a gunpowder explosion, as shown above. After confirming the presence of pain sensation and blanching, you rule out a full-thickness burn. You provide analgesia, run cold water over the burn, and debride blisters. Your supervising physician asks you which type of dressing would be best for this patient.

Answer:

Burn wounds are at high risk of infection as the skin barrier is compromised. They require adequate moisture and debridement for optimal healing. Historically, such burns were treated with a combination of paraffin-impregnated gauze and an absorbent cotton wool layer.11 Silver sulfadiazine cream has also been commonly used to manage burn wounds, but its efficacy has shown mixed evidence. It also requires twice daily reapplication which is often not feasible for burns being managed as an outpatient.

In a 2013 systematic review, Wasiak et al.12 examined 30 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effects of dressings on the healing of superficial partial-thickness burns. They concluded that hydrogel dressings shortened the time to complete wound healing compared to the standard of care with paraffin gauze or silver sulfadiazine (11.9 vs 13.6 days, P<0.02).13,14 Additionally, they highlighted RCTs that showed silver-impregnated dressings significantly shortened the time to complete healing and reduced the level of pain compared to the standard of care with SSD (7 vs 14 days, P<0.02).15,16 In many institutions, silver impregnated dressings like Acticoat have become the modern gold standard for management of most burn injuries.

Bottom line:

The evidence suggests that medicated dressings, hydrogels, and secondary dressings play a significant role in healing of burn wounds. At our institution, VGH, a common treatment for partial-thickness burns involves a combination of hydrogel paste (Intrasite Gel), a silver-based medicated dressing (Acticoat Flex 3), and a dry absorptive gauze layer. To apply this combination, a thick layer of Intrasite Gel is first spread over the epidermis. Then, Acticoat Flex 3 is placed on top, followed by a layer of dry gauze, which is secured with tape. This method necessitates dressing changes every three days. However, if two layers of Acticoat Flex 3 are used on top of the Intrasite Gel, the dressing can last up to seven days, reducing the frequency of changes needed in an outpatient setting. The figure below illustrates the common use of this combination in clinical practice.

Figure 4: Combination dressings applied to a second-degree burn. * Image taken by author from VGH wound information sheet. © 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY 4.0.

Frequently Asked Questions:

1. Should I deroof blisters for superficial burns?

Garg et al., in a prospective study of 27 patients with a total of 50 blisters, concluded that deroofing blisters, compared to leaving them intact, leads to significantly reduced healing time in superficial partial-thickness burn wounds (7.24 vs. 8.92 days, P<0.05).17 Deroofing allows moisture from the dressing to reach the dermal layer, promoting healing. Thus, it is advisable to deroof blisters using an antiseptic method.

2. Why does Acticoat need to be used with Intrasite? Can I use normal saline?

This question is common in burn units. Acticoat must be activated for the silver ions to reach the wound bed effectively. The preferred methods at our institution, VGH, involve using distilled water or Intrasite gel, with the latter being the gold standard due to its continuous moisture provision. It’s important to avoid using normal saline to activate Acticoat, as its salts can deactivate the silver ions.18

Case 3: Diabetic foot ulcer

Figure 5: A diabetic foot ulcer localized over the heel. Image taken from Wikimedia Commons. © 2008. This work is openly licensed via CC BY 3.0 DEED [16].

A 47-year-old female with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the ED with a wound that has become increasingly painful and has developed a foul-smelling discharge. She has normal recent ankle-brachial index (ABI), toe pressures, and foot x-ray results. After debridement, collection of wound swabs, and initiation of antibiotics, your supervising physician asks you which dressing would be optimal for this type of wound?

Answer:

Diabetic foot ulcers are complex and result from factors such as peripheral neuropathy, decreased blood supply, and high plantar pressures. It is important to assess the size and depth of the wound, in addition to its level of exudate.19 Off-loading pressure from the wound site is crucial in the chronic management of these wounds.

Selecting a dressing that provides an appropriately moist wound healing environment, absorbs exudates, and controls infection is important. In an RCT involving 134 patients, Jude et al. demonstrated that silver-containing hydrofiber dressings (Aquacel Ag) reduce the depth of the ulcer by half (0.13 cm vs. 0.25 cm, P=0.04) compared to calcium alginate dressings (Algosteril).20 Another RCT with 50 patients by Zhang and Xing showed that foam dressings, such as Mepilex Lite, reduce healing time (49.9 vs. 65.5 days, P=0.038) compared to Vaseline-impregnated gauze.21 These findings highlight the importance of using modern dressings that provide adequate cushioning and absorption qualities.

Bottom line:

Diabetic foot ulcers are complex chronic wounds that require both systemic and local wound management. There is strong evidence supporting the use of more expensive modern dressings, as highlighted in the RCTs mentioned above. An appropriate dressing for the case described would be a hydrofiber or foam dressing. A commonly used dressing is Mepilex Ag, which is a foam dressing that provides antimicrobial activity in addition to excellent exudate absorption. These wounds require follow-up by a wound care specialist to monitor wound healing and manage dressing changes.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Is there a role for negative pressure wound therapy in diabetic foot ulcers?

Negative pressure wound therapy involves applying subatmospheric pressure to the surface of an ulcer, enhancing healing by increasing wound perfusion. Game et al.’s systematic review indicates a reduction in granulation time for extensive open wounds after debridement for infection, necrosis, or following partial foot amputation.22 For simple, low-grade, non-infected ulcers, a foam dressing is suitable. It’s crucial to include debridement, off-loading, and revascularization in ulcer management, alongside selecting appropriate dressings.

Summary

Choosing the right dressing is essential for wound healing. There are hundreds of commercial dressings available, and we have highlighted just a few in the cases above. Keeping the following wound characteristics in mind can guide you in choosing the appropriate dressing:

1. Wound complexity and dressing cost (traditional vs. modern dressings)

2. Wound bed moisture (dry vs. exudative)

3. Likelihood of infection (medicated vs. non-medicated dressings)

This post was copyedited by Kurt Ebeling (University of Alberta Medical Student) and Daniel Ting.

Want to learn more? Here is another CanadiEM article on the approach to burns in the ED.

References

- 1.Dhivya S, Padma VV, Santhini E. Wound dressings – a review. BioMed. Published online November 28, 2015. doi:10.7603/s40681-015-0022-9

- 2.Calianno C. How to choose the right treatment and dressing for the wound. Nurs Manag (Harrow). 2003;Suppl:6-10, 12-14; quiz 14-15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14694861

- 3.Sinha SN, Free B, Ladlow O. The art and science of selecting appropriate dressings for acute open wounds in general practice. Aust J Gen Pract. Published online November 1, 2022:827-830. doi:10.31128/ajgp-06-22-6462

- 4.Dumville JC, Gray TA, Walter CJ, et al. Dressings for the prevention of surgical site infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online December 20, 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003091.pub4

- 5.Toon CD, Lusuku C, Ramamoorthy R, Davidson BR, Gurusamy KS. Early versus delayed dressing removal after primary closure of clean and clean-contaminated surgical wounds. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online September 3, 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010259.pub3

- 6.Cummings P, Del Beccaro MA. Antibiotics to prevent infection of simple wounds: A meta-analysis of randomized studies. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. Published online July 1995:396-400. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(95)90122-1

- 7.Heal C, Buettner P, Raasch B, et al. Can sutures get wet? Prospective randomised controlled trial of wound management in general practice. BMJ. Published online April 24, 2006:1053-1056. doi:10.1136/bmj.38800.628704.ae

- 8.Scott HC, Stockdale C, Robinson A, Robinson LS, Brown T. Is massage an effective intervention in the management of post-operative scarring? A scoping review. Journal of Hand Therapy. Published online April 2022:186-199. doi:10.1016/j.jht.2022.01.004

- 9.Commander S, Chamata E, Cox J, Dickey R, Lee E. Update on Postsurgical Scar Management. Seminars in Plastic Surgery. Published online July 26, 2016:122-128. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1584824

- 10.Tran B, Wu JJ, Ratner D, Han G. Topical Scar Treatment Products for Wounds: A Systematic Review. DS. Published online September 8, 2020:1564-1571. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000002712

- 11.Hudspith J, Rayatt S. First aid and treatment of minor burns. BMJ. Published online June 17, 2004:1487-1489. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1487

- 12.Wasiak J, Cleland H, Campbell F, Spinks A. Dressings for superficial and partial thickness burns. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online March 28, 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002106.pub4

- 13.Grippaudo FR, Carini L, Baldini R. Procutase® versus 1% silver sulphadiazine in the treatment of minor burns. Burns. Published online September 2010:871-875. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2009.10.021

- 14.Guilbaud J. European comparative clinical study of Inerpan: A new wound dressing in treatment of partial skin thickness burns. Burns. Published online October 1992:419-422. doi:10.1016/0305-4179(92)90044-u

- 15.Opasanon S, Muangman P, Namviriyachote N. Clinical effectiveness of alginate silver dressing in outpatient management of partial‐thickness burns. International Wound Journal. Published online September 21, 2010:467-471. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481x.2010.00718.x

- 16.Gong ZH, Yao J, Ji JF, Yang J. Effect of ionic silver dressing combined with hydrogel on degree II burn wound healing. Journal of Clinical Rehabilitative Tissue Engineering Research. 2009;13(42):8373-8376. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-8225.2009.42.040

- 17.Rakesh D, Garg R, Mittal R, Kathpal S, Kaur A, Singh K. Managing blisters in minor burns: Should they be deroofed? Indian J Burns. Published online 2021:31. doi:10.4103/ijb.ijb_25_20

- 18.Unknown -. ActicoatTM Flex 3 and Flex 7 – Application Guide . Vital . Published February 20, 2024. https://www.vitalmedicalsupplies.com.au/globalassets/ebos-nz/microsites/sn-wound-inf-solutions/acticoat-flex-application-poster.pdf

- 19.Shi C, Wang C, Liu H, et al. Selection of Appropriate Wound Dressing for Various Wounds. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. Published online March 19, 2020. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00182

- 20.Jude EB, Apelqvist J, Spraul M, Martini J. Prospective randomized controlled study of Hydrofiber® dressing containing ionic silver or calcium alginate dressings in non‐ischaemic diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetic Medicine. Published online February 14, 2007:280-288. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02079.x

- 21.Zhang Y, Xing SZ. Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers using Mepilex Lite Dressings: A Pilot Study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. Published online March 12, 2014:227-230. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1370918

- 22.Game FL, Hinchliffe RJ, Apelqvist J, et al. A systematic review of interventions to enhance the healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes. Diabetes Metabolism Res. Published online January 23, 2012:119-141. doi:10.1002/dmrr.2246

Reviewing with the Staff

Wounds are a common presentation in the ED, and being able to level up your knowledge on wound dressings will round out your expertise on this topic. Knowing the difference between traditional and modern dressings and when to use each is a key take-home of this open educational resource.