Your next patient is Tom, an otherwise healthy 22-year-old male. He has returned for the fourth time within the last 3 months for intermittent generalized abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A review of his previous visits reveals that he has been extensively worked up with a normal abdominal ultrasound, x-ray, and even a CT scan. He was also referred for endoscopy, which showed gastritis with a Mallory-Weiss tear and was started on pantoprazole without much benefit. He was also tested for Covid-19 twice, both of which were found to be negative.

You do a deep dive into Tom’s review of systems. None are significant or contributory except that Tom used to be a heavy marijuana smoker but has stopped over the last 6 months and only uses edibles now.

On physical Tom appears mildly dehydrated, and his abdominal exam is subjectively tender around the epigastrium, with no rebound or signs of peritonitis.

You can’t help but wonder whether Tom’s experiences are still somehow related to his cannabinoid intake, particularly given his extensive work up and seemingly refractory symptoms.

Background

A 2019 nationwide survey reports that 6.0% of Canadians aged 15 years or older report daily or almost-daily cannabis use.1 The unique socioeconomic pressures of the Covid-19 pandemic have further increased the prevalence of cannabis use.2,3

Two decades ago, an Australian case series first described the persistent nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain experienced by frequent users of cannabis, now commonly known as cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS).4–6

Diagnosis

There have been many authors that have tried to develop diagnostic criteria for CHS, but this has remained largely elusive.

| Table 1: Common clinical characteristics associated with Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS) |

| – Habitual or frequent cannabis use – Behaviour of frequent use of hot showers to temporarily alleviate symptoms – Reliance on cannabis for its antiemetic properties – Among patients using cannabis for self-treatment, a disbelief that cannabis can paradoxically be the cause of their symptoms.7 |

The route of administration may also alter the presentation of CHS. For example, compared to inhalation, edibles present less often with CHS and are more associated with psychiatric and cardiovascular symptoms. The pharmacokinetics mean that ingested cannabis lasts 4-24 hours whereas inhaled cannabis lasts 1-6 hours.8 Particularly amongst those that experience CHS, when actively nauseous and vomiting, ingestion of cannabis temporarily ceases, which only further complicates diagnostic accuracy given the extended and varied half-life of edibles.

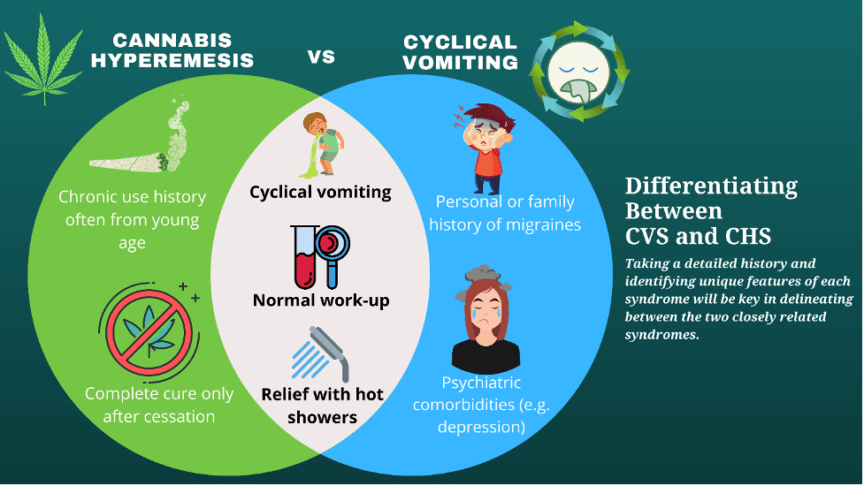

To complicate matters, CHS is often intertwined with cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) as both have similar presentations. Details on history will further help delineate cyclical vomiting from cannabis hyperemesis, though the management for both is similar.

Treatment

CHS patients typically do not respond well to the traditional antiemetics such as ondansetron or diphenhydramine. In more recent years it has been found that patients respond better to antipsychotics such as haloperidol or olanzapine.7,9

A recent small randomized control trial by Ruberto et al. showed similar improvement in symptoms, with less frequent rescue antiemetics and shorter time to emergency department departure stay when using 0.05 or 0.01 mg/kg IV of haloperidol versus 8 mg of ondansetron. Overall, the study found success with no significant adverse effects with a single dose of 0.05 mg/kg of haloperidol for the treatment of CHS.10

In a case report by Aziz et al., a patient with refractory symptoms to traditional antiemetics was found to have significant relief with 0.1% topical capsaicin cream applied over the epigastrium.11 Capsaicin cream is available in varying concentrations (0.025%, 0.075%, 0.1%) and has been shown to successfully treat CHS. Capsaicin is an active ingredient in chilli peppers and acts on TRPV-1 receptors. These receptors are often found near endogenous cannabinoid receptors and are thought to play a role in the regulation of the endocannabinoid system. TRPV-1 receptors also respond to high temperatures which provides a possible correlation for the relief seen in these patients by hot showers.11

While these pharmacological treatments show promise in treating CHS, only complete cannabis cessation has been shown to definitively stop CHS with symptoms resolving within 24-48 hours of cessation.5 Secondary to cyclical vomiting, hematemesis and/or gastritis can be treated with proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers. Any associated dehydration, acute kidney injury and electrolyte imbalances can be treated with fluid resuscitation. Pneumomediastinum has also been reported in patients as a significant but rare complication.6,12

Case Conclusion

You inform Tom that his symptoms are very likely due to cannabis use. Tom is quite surprised by this suggestion as he has been using it for months without any side effects. As you tease out the intermittency of his symptoms, it becomes clear that when he feels unwell, he temporarily stops consuming cannabis. You describe that although cannabis may initially or sometimes temporarily improve nausea, repetitive use for some individuals causes a chemical switch in their brain that makes their body paradoxically experience unrelenting nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal upset.

Tom responds well to haloperidol 1 mg IV and fluids and he is able to tolerate a sandwich and juice. Tom is again advised to avoid any cannabis products and an additional oral dose of haloperidol is prescribed to take home as needed for his symptoms as the cannabis washes out of his system over the next few days. Tom is also reminded that taking hot showers also works well in temporarily improving symptoms.

[bg_faq_start]Bonus – What about the QT Interval?

An astute medical student prior to discharge, asks you whether haloperidol is safe in vomiting individuals, as their hypokalemia may already prolong their QT interval. She remembers reading about a Black Box warning of warning of Torsades de Pointes from QT prolongation with haloperidol.

Several authors including Meyer-Massetti et al. have critically looked at the adverse cases with that recommendation.13 Amongst their conclusions is that Haloperidol’s QT prolongation effect is dose dependent, and higher incidence of adverse cases associated with haloperidol coincides with older cases and the higher use of haloperidol in the past compared to present day. In Ruberto et al. study of 0.05-0.1 mg/kg IV found no significant increase in QT prolongation or Torsades de Pointes, with only two dystonic reactions found in the 0.01 mg/kg dose group.10 Additionally, low (<2 mg) to moderate doses (<5 mg) of haloperidol in particular are well known antiemetic doses used post-operatively regularly with minimal to no risk of cardiac toxicity.14

Many authors now conclude that a cumulative dose less than 2 mg of haloperidol is not associated with significant prolongation QT or increased risk of Torsades de Pointes. Additionally, at these low doses, screening EKG and cardiac monitoring can be routinely omitted.14 With a half life ranging from 14.5-36.7 hours an additional one to two oral doses of haloperidol as needed would be a safe and reasonable prescription to provide as outpatient management of resolving CHS.

[bg_faq_end]Take Home Points

- Think of marijuana use when seeing young adults with abdominal pain. Majority of marijuana related hospitalizations exclusively occur in the young adult population 15-25 years old.

- Significant stigma and reluctance to admit any cannabinoid use is a common characteristic of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.

- Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome and cyclical vomiting syndrome are similar and sometimes temporally linked syndromes.

- Edible cannabis products can still be associated with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.

- Low dose haloperidol < 2 mg IV can be safely used with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.

This post was edited and copyedited by Daniel Ting.

References

- 1.Statistics Canada, Rotermann M. What has changed since cannabis was legalized? Published online 2020. doi:10.25318/82-003-X202000200002-ENG

- 2.Bartel SJ, Sherry SB, Stewart SH. Self-isolation: A significant contributor to cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Substance Abuse. Published online October 1, 2020:409-412. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1823550

- 3.Imtiaz S, Wells S, Rehm J, et al. Cannabis Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada. Journal of Addiction Medicine. Published online December 14, 2020. doi:10.1097/adm.0000000000000798

- 4.Cox B, Chhabra A, Adler M, Simmons J, Randlett D. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Case Report of a Paradoxical Reaction with Heavy Marijuana Use. Case Reports in Medicine. Published online 2012:1-3. doi:10.1155/2012/757696

- 5.Allen JH. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut. Published online November 1, 2004:1566-1570. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.036350

- 6.Sorensen CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, Phillips KT, Monte AA. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment—a Systematic Review. J Med Toxicol. Published online December 20, 2016:71-87. doi:10.1007/s13181-016-0595-z

- 7.Randall K, Hayward K. Emergent Medical Illnesses Related to Cannabis Use. Mo Med. 2019;116(3):226-228. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31527946

- 8.Cannabis: Inhaling vs Ingesting [infographic]. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-10/CCSA-Cannabis-Inhaling-Ingesting-Risks-Infographic-2019-en.pdf

- 9.Richards JR, Gordon BK, Danielson AR, Moulin AK. Pharmacologic Treatment of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Pharmacotherapy. Published online May 12, 2017:725-734. doi:10.1002/phar.1931

- 10.Ruberto AJ, Sivilotti MLA, Forrester S, Hall AK, Crawford FM, Day AG. Intravenous Haloperidol Versus Ondansetron for Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (HaVOC): A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Published online June 2021:613-619. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.08.021

- 11.Aziz A, Waheed T, Oladunjoye O, Oladunjoye A, Hanif M, Latif F. Topical Capsaicin for Treating Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome. Neri M, ed. Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine. Published online November 27, 2020:1-4. doi:10.1155/2020/8868385

- 12.Spontaneuos pneumomediastinum secondary to cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. An Sist Sanit Navar. Published online August 2019. doi:10.23938/assn.0635

- 13.Meyer-Massetti C, Cheng CM, Sharpe BA, Meier CR, Guglielmo BJ. The FDA extended warning for intravenous haloperidol and torsades de pointes: How should institutions respond? J Hosp Med. Published online April 2010:E8-E16. doi:10.1002/jhm.691

- 14.Schaub I, Lysakowski C, Elia N, Tramèr MR. Low-dose droperidol (≤1 mg or ≤15 μg kg−1) for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in adults. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. Published online June 2012:286-294. doi:10.1097/eja.0b013e328352813f

Reviewing with the Staff

With the legalization of cannabis in Canada and the increase in recreational drug use since the pandemic, the prevalence of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is an increasing underrecognized differential particularly amongst adults less than twenty-five years old. Haloperidol is an old medication that is increasingly being recognized as an effective medication for the treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, but carries a black box warning of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes that worry and deter many clinicians from considering its use. This case scenario aims to highlight key clinical characteristics to help emergency physicians more confidently recognize and empirically treat cannabis hyperemesis syndrome in the emergency department.