A 70-year-old male calls EMS with a 3-day history of shortness of breath. He sleeps in a chair because his breathlessness is made worse while lying on the flat of his back. He is working hard to breath and has difficulty speaking in full sentences. Physical examination reveals an elevated JVP, a third heart sound, and wheezes bilaterally with fine inspiratory crackles. He also has bilateral pitting edema to his hips. Vitals include a heart rate of 125, blood pressure of 170/105, respiratory rate of 32, oxygen saturation of 91% on room air, and temperature of 37.1. His ECG shows sinus tachycardia.

Can Ventolin improve wheeze in heart failure?

Breathlessness in heart failure patients led James Hope to coin the term “cardiac asthma” in 18331, and by 1854 cardiac asthma was considered a disease state. Sir William Osler’s classic description (1897) has withstood the test of time: “In the case of advanced arteriosclerosis, there are often attacks of dyspnea of great intensity recurring in paroxysms, often nocturnal. The patient goes to bed feeling quite well, and in the early morning hours wakes in an attack which, in its abruptness of onset and general features, resembles asthma.”1,2

The cause of these symptoms is not obstructive bronchoconstriction like in asthma, but a reflex bronchoconstriction that results from pulmonary congestion due to an increase in pulmonary venous hypertension (PVH). The increase in PVH is attributed to a failing left ventricle, which causes a rise in hydrostatic pressure at the capillaries surrounding the alveoli. This causes fluid to leak into the airspaces impairing oxygenation and ventilation, ultimately resulting in patients with wheeze in heart failure.3,4

While Ventolin is the first line treatment for asthma & COPD by relieving airway obstruction through its β2 agonist effect of bronchodilatation, its utility in cardiac asthma is controversial. Furthermore, Ventolin can also increase heart rate by its β1 agonist effect on the myocardium. Given the pathogenesis of cardiac asthma there is limited evidence supporting or refuting the use of Ventolin to reverse the effects of reflex bronchoconstriction.3,4

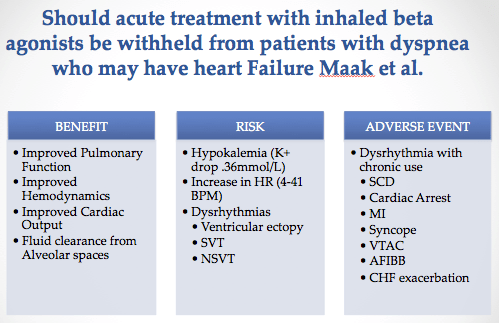

Two systematic reviews have been published on this topic. One found that it may improve pulmonary function, hemodynamic stability, and fluid clearance from the alveolar space, but also noted side effects including hypokalemia, tachycardia, and dysrhythmias. Adverse cardiac events such were also noted with chronic administration. The limitation of this study is that the majority of individuals being treated were in compensated heart failure5 and can not necessarily be extrapolated to patients with acute decompensated heart failure patients. Another review analyzed the use of HF medications and ventolin in the pre-hospital setting and did not find that it improved vital signs.6

In conclusion, the current evidence does not support or refute the use of ventolin in cardiac asthma. Identifying the etiology behind CHF decompensation will determine the appropriate therapeutic interventions. The patient’s medical history, vital signs, and physical exam may determine whether it should be used. It is reasonable to consider Ventolin therapy in patients with CHF who have a past medical history of asthma or COPD.

Case Resolution

The Paramedics identified the patient as being in severe heart failure. History and physical exam findings strongly supported an acute CHF exacerbation. Management en route included supplemental oxygen and SL nitroglycerin (0.4mg). In consultation with a physician, CPAP was initiated.7 The patient was admitted for heart failure secondary to medication non-compliance.

This post was copy-edited and uploaded by Brent Thoma.

References

Reviewing with the Staff

This post was written in response to a paramedic asking about \'cardiac asthma.\' To be honest, before Dr. Benjamin tackled it I wasn\'t aware of such a disease entity as the term seems to have gone out of practice. However, the question at the heart of this inquiry - whether ventolin should be used in a patient with congestive heart failure who has a wheeze - is a good one. While the literature is scant and lukewarm, I agree with Dr. Benjamin\'s conclusion that it is reasonable to trial this medication in patients who have a history of cocommittent asthma, COPD, or even a longstanding smoking history. Ultimately, the risk of this agent causing problems is low and the pathophysiology, while slightly different, still relates to bronchospasm.