Ruth, a 79 year old lady presents to the emergency department after a fall now unable to ambulate. Ruth is the sole care provider for her sick husband and is anxious to go home and look after him. Your x-rays show she has broken her right hip and will require admission and surgery. You wonder how to tell her this bad news.

Busy shifts in the emergency department are often fragmented into short encounters with our patients. Even as clerks, we do multiple things at once; writing our notes, handing important orders to nursing staff, and waiting for an admitting service to call you back. We talk to each patient, examine them, think through our investigations and work through their results with the aim of reaching a diagnosis and making a treatment plan, and it’s all very systematic, until we have to go tell the patient the bad news about what is happening to them.

Breaking bad news effectively is important because it shapes the entire healthcare experience for a patient or their family from that point onwards. It is hard for us as ED clinicians, whether medical students, residents or staff, because we have little time to prepare before talking to patients and their families, and we often experience the same feeling of helplessness or guilt when we cannot change the outcome for the patient. Despite the thick-skinned facade many clinicians are able to hold, witnessing our patients’ distress is challenging. As a medical student, there is the added stress of having these conversations for the first time and working through the awkwardness.

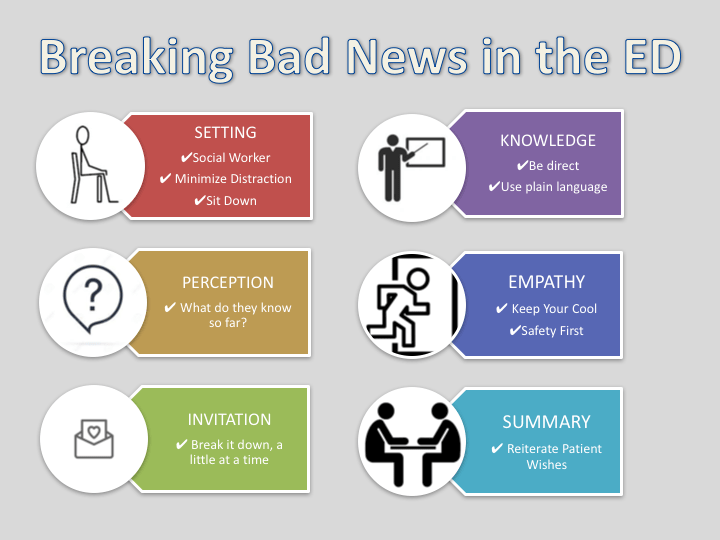

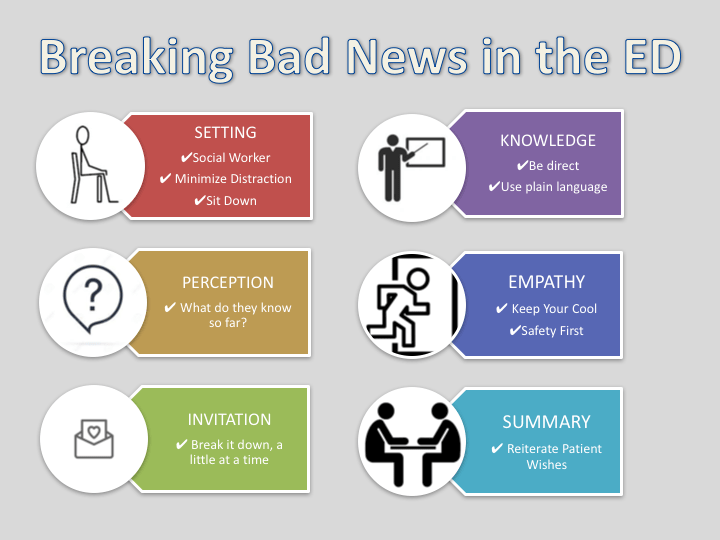

The SPIKES mnemonic is a very common methodology used for delivering bad news1. It was created by oncologists for delivering bad news to cancer patients, but can be adapted to all settings.

SPIKES

- Setting: Pick a private and quiet place to talk to the patient

- Perception: What is the patient’s perception of their medical condition at present

- Invitation: How much do they want to know?

- Knowledge: Share the news

- Empathy: Take time to allow the patient to express their emotions and respond

- Summary: Patients often miss the details after the initial shock of bad news, summarize the main issues and plan moving forward.

This method is often used by medical students as it provides a systematic way of delivering bad news in a time when clerks may be flustered by responsibility, upset by the incident, and struggling to plan the conversation.

What you say and the order it’s said in are definitely important, but the SPIKES protocol is so much more meaningful out of isolation when pieced together with real-life advice from expert staff physicians who have made breaking bad news work well in the ED

Approach to Breaking Bad News – SPIKES with PEARLS from ED Staff

[bg_faq_start]Setting

“Make sure you have enough time”

(Dr. Jonathan Sherbino @Sherbino)

Unlike a scheduled clinic appointment, the ED pulls you in multiple directions at once. If you’re going to talk to a family, try to make sure it’s not while you’re waiting for a consultant to call you back or you are in the middle of something else.

If your phone goes off and you leave the room mid-discussion, it can feel betraying for the family to be left alone. It’s not often realistic to cut yourself off from a busy department if you are the staff, but do your best to minimize distractions and interruptions.

“[Have a] social worker handy next to me so when I leave the room they can continue to provide support”

(Dr. Raj Grewal)

The setting isn’t only about having a quiet, private space, which in itself is difficult in the bustle of the ED. After the short amount of time you spend with the family, a supportive setting includes leaving them with someone who can continue to keep that supportive environment.

“Sit with the patient or family – this goes a long way in terms of empathy and can give the impression that you spent a longer time with them”

(Dr. Julian Owen @JulianOwenEM_CC & Dr. Alison Fox-Robichaud @DrFoxRob)

Make this one of the times that you actually sit down to talk to a patient and their family. Sitting at eye-level shows that you are not rushing away to see your next patient.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Perception

“Ask what the patient or family understand about tests that were done, why they were done, what they know so far.

I’ve sometimes gone in dreading a diagnosis of something like cancer, and the patient says they already knew or had a good idea about that.” (Dr. Guarav Gupta)

Ask the patient what they know so far so you know what knowledge base you are working with and where to start.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Invitation

“I tell them a little at a time, let them take it in and ask them if they want to ask me more questions right now…

If the family ask questions, I turn it to the patient and state that I can provide an answer, but it is up to the patient to decide what questions they have right now and that there will be lots of time to ask questions

(Dr. Michelle Welsford @WelsfordM)

Asking a patient or their family how much detail or information they would like can often be confusing if they are unsure of the magnitude of what they are dealing with. After breaking the crux of the news, consider asking again how much more they would like to know at that point.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Knowledge

“Identify the people in the room and who it is that you should be speaking with such as spouse, other 1st degree relative, POA”

(Dr. Andrew Worster @ProfBEEM)

After you introduce yourself, you want to know who the people in the room are and whether they should in fact be in the room. When sharing knowledge, make sure you are talking to the patient or most responsible family member as the questions and decisions should be of their making.

“Tell a story.”

(Dr. Alim Pardhan @AlimPardhan)

Talk about what has happened from the time they left the house up until this point in the ED to fill in the gaps. The family often doesn’t know what happened between EMS picking up their loved one and them being wheeled into a resuscitation room. End the short story with the news and be straightforward E.g. this is what EMS did, this is what we did in the ED, but we could not restart their heart and they have died.

“You do have to say ‘they died’ at some point”

(Dr. Alim Pardhan @AlimPardhan)

After what can be a complicated story to the patient, we have to be upfront with the diagnosis or result. Vague statements like “they are no longer with us” or “they have left us” are often not to the point and can lead to miscommunication and misunderstanding.

“No one hears anything/remembers anything after you say the ‘big’ thing”

(Dr. Jonathan Sherbino @Sherbino)

Make sure you are done the important parts of your story then get to the point with the news. They will need time to process after this and you likely won’t be able to add much else.

“Use plain language that they can understand and check in with them

‘Do you understand what I mean by _____?’

Use terms like “death” or “cancer” instead of “passed away” or “mass/growth” (the latter only if imaging suggest malignancy… don’t create unnecessary fear if things aren’t clear).

(Dr. Julian Owen & Dr. Alison Fox-Robichaud)

“If it’s an ongoing resuscitation, reassure them that you will update them with any changes and ensure that you do so yourself. Assigning this task to someone else including the social worker can lead to miscommunication and a disaster”

(Dr Andrew Worster @ProfBEEM)

Sharing knowledge is often a multi-step process as you continue to update a patient’s family of their status in the case of a resuscitation. Keeping the family in the loop by assigning the dedicated role to someone who is not otherwise involved in the resuscitation will assure the job is done in a timely and appropriate manner.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Empathy

“Don’t lose your cool no matter how insulting or angry they become, instead, be prepared to just leave…always maintain easy access to the door”

(Dr. Andrew Worster @ProfBEEM)

Breaking bad news is hard for us, but bearing the news is not only scary, but often comes as a surprise. Many patients will react with sadness, but there are those who will act with anger or distrust and can blame you for the outcome of their loved one. Stay cool and keep your safety first.

[bg_faq_end] [bg_faq_start]Summary

Take a moment to summarize what the plan is so patients understand that there are steps in place that are being taken care of, whether that is calling a consultant, talking to palliative care, or allowing natural death.

For discussions about withdrawing care in the ED, remind the patient that despite them voicing their loved ones wishes, they did not make the decision to pursue or withdraw care.

“I always tell them, I want to thank you for telling me about [the person] so we could honour them by treating them how they would want. I want to make it clear that this was not a decision or a choice, but rather being true to them”

(Dr. Michelle Welsford @WelsfordM)

“Take care of yourself – we can sometimes be ‘second victims’ in high stress situations”

(Dr. Teresa Chan @TChanMD)

Breaking bad news doesn’t end when you leave the room. It continues for the patient, but it also continues for you. Take some time to process and recognize when you need a few moments to regroup.

[bg_faq_end]Here are some excellent resources that exist already available through FOAMsearch.net:

This post by LITFL goes through the PLIEE approach:

- Prepare, Location, Introduction, Information, and End

- This reminds you to introduce your role and the others present in the discussion

This post by First10EM is a case-based approach that divides the process into three parts:

- Before entering the room, in the room, and leaving the room

- Before the room: One of the benefits of being a medical student is the added bonus of time. Take your time before going into a room to prepare yourself, address your emotions and make a plan

- In the room: Be clear about your news “I.E. John has died”

- Leaving the room: We have to go back to work – acknowledge both the patient and your own grief reaction

This post was edited and uploaded by Megan Chu

- 1.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES—A Six‐Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer. The Oncologist. August 2000:302-311. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302

Reviewing with the staff

As an Investigating Coroner, I have the privilege of meeting a patient’s loved ones one the worst day of their lives. I speak to them at various points after that day, after the autopsy, and months later when the reports are final. Families tell me how compassionate the physicians were, or how disappointed they were with the way they were treated. Believe me when I say that they will remember their brief interaction with the healthcare team for the rest of their lives. Dr. Nasser’s post is full of pearls from our attendings at McMaster emergency medicine on how to deliver bad news in the best way possible.

Breaking bad news can be a very intense experience. Remember that the family and loved ones are experiencing a huge amount of emotion. They may be overwhelmed, numb, angry and in disbelief or denial. Grief isn’t like how it is portrayed in the movies. Everyone processes bad news in different ways. I have seen everything from nervous laughter to anger at the physicians. When you break bad news, you are in the room with the family and all the memories (good and bad) they shared with the deceased person. So, be gentle with yourself. Understand that breaking bad news can be a very intense experience that may take time to process. Don’t let yourself be the “second victim” to paraphrase Dr. Chan. Reach out to colleagues for support. When it is done well, breaking bad news is the final way we can honour the memory of the dead.