A 52-year-old male presents with chest pain. He arrests upon arrival to the Emergency Department and is found to be in ventricular fibrillation. You provide good CPR and defibrillate the patient, and treat him with doses of epinephrine and amiodarone in keeping with the ACLS algorithms. The patient continues to be in ventricular fibrillation despite even trying dual-sequential defibrillation and you are running out of other options for treatment.

Should ß-Blockers be tried as the next adjunct? This post provides an overview of the physiology of ventricular fibrillation and outlines the potential adverse events of high-dose epinephrine/beneficial effects of beta blockers in these patients before summarizing the evidence for the use of beta blockers in ventricular fibrillation.

Physiology of Ventricular Fibrillation in Cardiac Arrest

Ventricular fibrillation (VF) is the most common arrhythmia associated with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.1 Myocardial oxygen consumption increases more than 4-fold in ventricular fibrillation relative to rest.2 Furthermore, during cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), coronary blood flow may be reduced to levels as low as 20-40% of resting values.3 Epinephrine has been a longstanding treatment for these patients, however, the literature has not shown an increase in survival rates with higher doses.4

How could Epinephrine cause HARM in Cardiac Arrest?

- Epinephrine causes selective vasoconstriction due to its actions on alpha-2 adrenergic receptors. Although it increases coronary perfusion pressure, epinephrine can cause myocardial dysfunction and new arrhythmias.5,6

- The activation of ß-adrenoreceptors by epinephrine causes an increase myocardial oxygen consumption via its positive chronotropic and inotropic effects.7,8

- The ß-1 stimulation of epinephrine promotes hyperphosphorylation of ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) in the myocardium, leading to excess calcium influx into the cytoplasm which further contributes to electrical instability, triggering arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.9,10

- Epinephrine also acts in the pulmonary circulation producing an increase in a right-to-left shunt and alveolar dead-space ventilation, worsening ischemia.6

The above potential harms may explain why improved survival rates have not been observed with higher doses of epinephrine.4

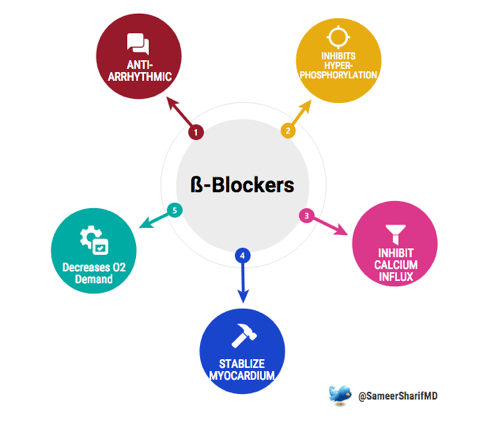

Physiological Benefits of ß-1 Selective Blockade with Esmolol

Esmolol is ß-1 specific with the fastest onset of action and the shortest half-life of all ß-blockers (9 minutes). It has been shown in in vitro studies analyzing action potential restitution curves to suppress epinephrine-mediated hyperphosphorylation of RyR2, electrically stabilizing the myocardium by inhibiting excessive myocardial calcium influx and blocking epinephrine’s effect on electrical restitution.10

From Lab to Bedside: Evidence for ß-Blockers in Cardiac Arrest

De Oliveira et al2 published a systematic review regarding the use of ß-blockers for the treatment of cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia. They found 12 animal studies, 10 case reports, and 2 human clinical papers. The data from the animal studies, however limited, were promising in support of the effectiveness of ß-1 selective blockade in refractory ventricular fibrillation in cardiac arrest.2

The first of the human studies by Nademanee in 2000 was a comparative prospective study analyzing the efficacy of sympathetic blockade in reverting shock-refractory VF in 49 post-MI patients. The ß-Blockade strategy included left-stellate ganglionic block, esmolol, and propranolol.11

The next human study by Miwa in 2010 was a prospective observational analysis evaluating the effects of landiolol, an ultra-short-acting ß-1 selective blocker, on electrical storm refractory to class III anti-arrhythmic drugs in 42 consecutive electrical storm patients.12

More recently, Driver et al published a retrospective observational analysis in a single academic urban county hospital looking at the use of esmolol after failure of standard CPR to treat patients with VF in 2014 with 25 patients.13

Though limited by their small size, all three studies showed a signal of benefit for the use of ß-Blockers for refractory VF.

Take-Home Message

The evidence, while mounting, is not robust enough to recommend the routine use of ß-blockers in refractory ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest. However, I would consider using it as part of the “kitchen-sink” mentality. If you’ve tried everything and nothing has worked, it is reasonable to CONSIDER the use of a short acting ß-1 selective blocker, such as esmolol, in consultation with your team members and consultation services.

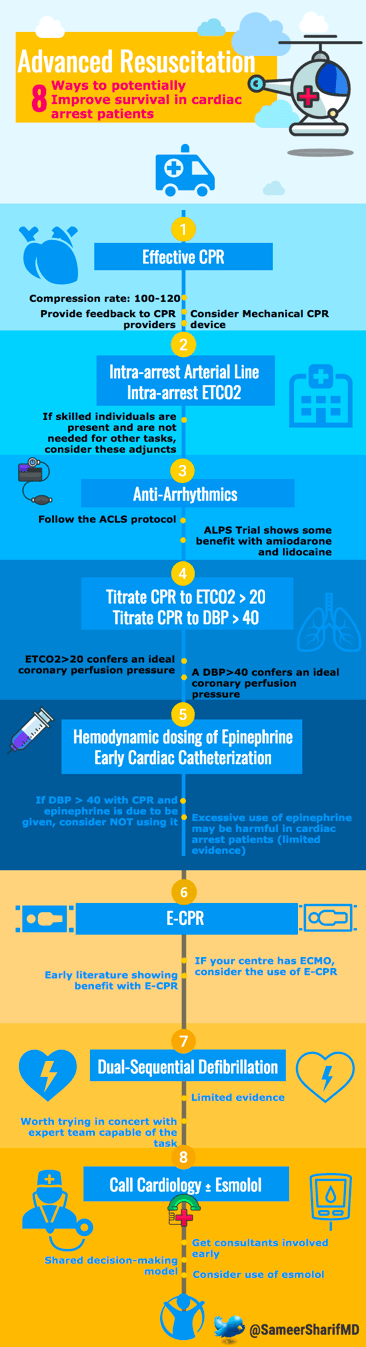

For those interested in further thought provoking ideas, consider the below infographic on some additional resuscitation ideas that go beyond the scope of ACLS.

This post was copy-edited by Chitbhanu Singh (Junior Editor). This post was the winning entry into the 2017 CanadiEM Essentials of EM Fellow competition.

References

Reviewing with the Staff

In patients with refractory VF unresponsive to conventional therapy, it may be reasonable to try beta-blockers. Prior to use I would ensure CPR being provided is exceptional, defibrillation with adequate pad contact/paddle pressure and maximum energy has been tried (including possibly dual sequential defibrillation), and anti-arrhythmic therapy has been exhausted. If your centre has E-CPR capability or mechanical CPR devices allowing intra-arrest coronary angiography, attempts should be made to treat the underlying cause, which is an acute MI in most cases. More data is needed before routine use of beta-blockers in this setting, but available literature suggests a possible benefit in highly selected patients.