Background

Shock is a state of cellular and tissue hypoxia caused by reduced oxygen delivery or increased oxygen consumption. We tend to use the patients systolic blood pressure (SBP) as our main diagnostic test for shock as it is readily available and simple to assess. Therefore, patients with a SBP of 90 mmHg or less are considered to be in shock until proven otherwise. Caution should be noted for special populations such as pediatrics, geriatrics or hypertensive patients who have different cut-offs for acceptable blood pressures. In these cases, consider other indicators of poor perfusion such as the Shock Index (SI), which is a ratio of heart rate to SBP.1 This is especially useful when those you suspect are in shock present with normal triage vitals. With mortality from shock exceeding 50% in certain cases it is vital that medical trainees be able to recognize, formulate an approach to and identify the possible underlying etiologies for undifferentiated shock.

Presentation

While shock can take on many forms, there are certain easily identifiable clues to look out for while in the emergency room. Patients which could be in shock, or at risk of, may be ill appearing or have an altered mental status (AMS). They will likely be tachypneic with a respiratory rate >20, tachycardic at >100 bpm and have decreased urine output defined as less than 0.5 mL/kg per hour. However, the strongest predictors of patient outcomes and the most accurate indicators of tissue hypoperfusion are the arterial base deficit and lactate.2 Simply put, the less oxygen our tissues receive, the more anerobic respiration takes place and the more lactic acid is produced. To compensate our body uses up more bicarbonate to buffer the increasing lactic acid which in turn lowers the base deficit. Therefore, patients with a dropping bicarbonate or increasing lactate are at serious risk of circulatory insufficiency with subsequent multi organ failure.3

Assessment and Investigations

Your assessment for hypotensive patients should begin like any other – with a focused history (can be from the patient or collateral from family/EMS) and physical exam. In order to stay focused and not get overwhelmed, let your history guide your physical exam. For example, patients which you suspect are suffering from sepsis should be thoroughly checked over for possible sites/sources of infection while trauma patients will need a primary survey looking for signs of internal or external blood loss.

Orders for investigations should be broad and include ABG/VBG, CBC, lytes, iCa, Mg, PO4, urea, Cr, glucose, CK, Troponin, INR, PTT, LFTs, TSH/Free T3/Free T4, beta HCG and urinalysis.

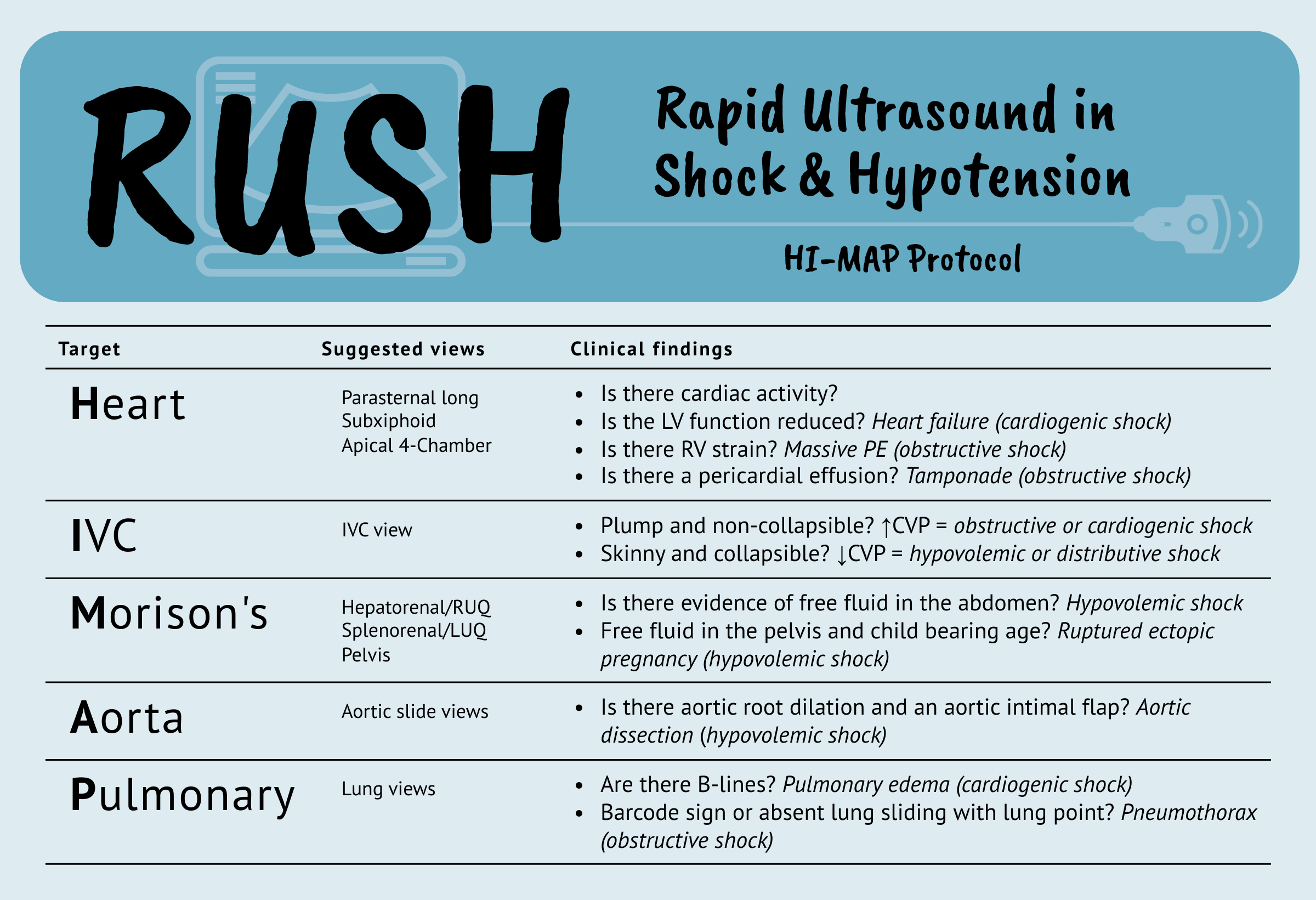

There are several bedside tests we can use to rapidly narrow our differential diagnosis. Consider an ECG which can unmask an underlying myocardial ischemia, cardiac tamponade or pulmonary embolism; a CXR which can clue us into congestive heart failure or pneumonia; or bedside ultrasound which can reveal free fluid or volume depletion. In the era of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) there are a number of protocols to consider when approaching the undifferentiated hypotensive patient.8 The International Federation for Emergency Medicine (IFEM) has previously described a Sonography in Hypotension and Cardiac Arrest (SHoC) protocol which is widely accepted and was reviewed by CanadiEM here.9 Another popular choice amongst ED physicians is the Rapid Ultrasound for Shock and Hypotension (RUSH) exam which employs the ‘HI MAP’ approach. Using this protocol, clinicians should use the phased array probe to obtain Heart, IVC, Morison’s pouch, Aorta and Pulmonary views.10 With practice, the RUSH exam can be completed in under 5 minutes and reveal both a diagnosis and/or type of shock.

Categories of Shock

Although it may be easy to recognize a patient in shock, more vital is determining the cause of shock. There are four main types of shock based on the underlying mechanism: Hypovolemic, Distributive, Cardiogenic and Obstructive. When a patient presents with undifferentiated hypotension, all of these differentials should be in your back pocket. To simplify this concept further, you can think of shock as a disruption in the PUMP (i.e., the heart/what surrounds the heart), the PIPES (i.e., blood vessels) or the TANK (i.e., intravascular volume).

Hypovolemic Shock

Hypovolemic shock is a result of decreased intravascular volume. The two main causes of hypovolemic shock are dehydration from fluid losses (e.g., GI losses from vomiting and diarrhea) or blood loss from trauma (also known as hemorrhagic shock). Initial decreases in blood volume may cause an increase in heart rate, baroreceptor activation and peripheral vasoconstriction resulting in a slight bump of the blood pressure. Acidemia is the first sign of hemorrhagic shock as blood flow is shunted away from noncritical organs and their cells produce and release lactic acid. Once cardiovascular reflexes are no longer able to compensate for the hemorrhage, cardiac output declines and the patient becomes hypotensive.

Treatment for hypovolemic shock requires volume resuscitation (i.e. fill the tank). Prevent ongoing losses through the use of tourniquets, direct compression or pelvic binders. Begin IV crystalloids and an infusion of packed red blood cells (pRBCs) if there is evidence of poor organ perfusion or an expected 30 minute delay in hemorrhage control. In cases of massive hemorrhage, consider a balanced transfusion of pRBCs, platelets and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) in a ratio of 1:1:1.4

Distributive Shock

Distributive shock is a result of peripheral vasodilation and fluid extravasation. The most common cause of distributive shock is septic shock due to severe infection and inflammatory mediators circulating in the blood. The infection and sequalae of associated symptoms lead to hypovolemia, cardiovascular depression and systemic inflammation. Leaky capillaries result in intravascular depletion and contribute to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), kidney and liver dysfunction.5 Other types of shock which fall under this category include anaphylactic shock, inflammatory shock and neurogenic shock.

Treatment for septic shock includes adequate oxygenation (target SpO2 >90%), fluid resuscitation and broad spectrum antibiotics. Patients who fail to respond to volume restoration should begin vasopressor support with norepinephrine infused at 0-5 mcg/min (i.e., squeeze the pipes!).6 Locating the source of infection should be prioritized after volume resuscitation and pressors have been initiated.

Cardiogenic Shock

Cardiogenic shock is a result of a poorly contracting heart. While poor contractility can be a secondary to other types of shock such as sepsis, pure cardiogenic shock is usually caused by an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), cardiomyopathy, conduction delay or cardiac structural damage.7 The other way in which cardiogenic shock can present is in arrhythmias such as profound bradycardia in the setting of an anterior STEMI or ventricular tachycardia with a pulse. In each of these cases, the heart is unable to contract effectively leading to systemic hypoperfusion, evidenced by hypotension, cool and mottled skin and lactic acidosis with organ dysfunction.

Treatment should focus on supporting forward flow and correcting arrhythmias. Consider administration of vasopressors such as norepinephrine at 0-5 mcg/min. Perform transcutaneous pacing for those with a severe bradycardia or synchronized cardioversion in ventricular tachycardia with a pulse. Optimize patient conditions using pressors and then if indicated use non-invasive ventilatory methods to mitigate increased work of breathing. Finally, treat underlying causes by getting the patient to the cardiac catherization lab or providing mechanical circulatory support.

Obstructive Shock

Obstructive shock is a result of external pressures which reduce the heart’s ability to pump. The three most common causes are massive pulmonary embolism, tension pneumothorax and cardiac tamponade. In massive pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in the proximal pulmonary artery causes too much pressure for the right ventricle to overcome. In tension pneumothorax, air leaks between the visceral and parietal pleura causing lung compression and an increase in pressure which shifts the heart and great vessels over. In cardiac tamponade, fluid collects between the heart and the pericardium impairing the heart’s ability to fill and contract effectively.

The most important (and only) treatment for obstructive shock is to alleviate the obstruction. This includes thrombolysis in massive PE, needle decompression and placement of chest tube in tension pneumothorax and a pericardiocentesis in cardiac tamponade.

Key Takeaways

- Keys to reducing mortality in shock are early recognition, rapid determination of the underlying cause and swift treatment!

- The cause of shock may be readily identifiable based on the patients presentation and history.

- Incorporation of POCUS protocols can be done at the bedside and assist in your early diagnosis of shock.

Download the infographic here.

References

- 1.Koch E, Lovett S, Nghiem T, Riggs R, Rech M. Shock index in the emergency department: utility and limitations. Open Access Emerg Med. 2019;11:179-199. doi:10.2147/OAEM.S178358

- 2.Singer M, Deutschman C, Seymour C, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.0287

- 3.Puskarich M, Jones A. Shock. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2023:34-41.

- 4.Woolley T, Thompson P, Kirkman E, et al. Trauma Hemostasis and Oxygenation Research Network position paper on the role of hypotensive resuscitation as part of remote damage control resuscitation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(6S Suppl 1):S3-S13. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001856

- 5.Helman A, Gray S, Morgenstern J, Spiegel R, Kovacs G, Simard R. Sepsis and Septic Shock – What Matters. Emergency Medicine Cases. March 2019. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/sepsis-septic-shock/

- 6.Djogovic D, MacDonald S, Wensel A, et al. Vasopressor and Inotrope Use in Canadian Emergency Departments: Evidence Based Consensus Guidelines. CJEM. 2015;17 Suppl 1:1-16. doi:10.1017/cem.2014.77

- 7.Henning D, Kearney K, Hall M, Mahr C, Shapiro N, Nichol G. Identification of Hypotensive Emergency Department Patients with Cardiogenic Etiologies. Shock. 2018;49(2):131-136. doi:10.1097/SHK.0000000000000945

- 8.Seif D, Perera P, Mailhot T, Riley D, Mandavia D. Bedside ultrasound in resuscitation and the rapid ultrasound in shock protocol. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:503254. doi:10.1155/2012/503254

- 9.Atkinson P, Taylor L, Milne J, et al. Does Point of Care Ultrasound Improve Resuscitation Markers in Undifferentiated Hypotension? An International Randomized Controlled Trial From The Sonography in Hypotension and Cardiac Arrest in the Emergency Department (SHoC-ED) Series. Cureus. 2020;12(8):e9899. doi:10.7759/cureus.9899

- 10.Weingart S, Duque D, Nelson B. Rapid Ultrasound for Shock and Hypotension – the RUSH Exam. EMCrit. May 2009. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://emcrit.org/rush-exam/

Reviewing with the Staff

Dr. Woods is an emergency physician and STARS Transport Doc located in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. He founded the FRCPC Emergency Medicine Training Program at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) and currently serves as Program Director for the Clinician Educator Diploma Program. He is actively involved in medical education research and serves as a Decision Editor for education scholarship for the CJEM.