It’s your first Emergency Medicine shift in clerkship. You’re asked to see a 25-year-old female with abdominal pain. What are things you want to make sure you ask about and examine, and how should you document your assessment without spending most of your shift on paperwork?

Documenting patient encounters is a core skill in all medical specialties; in fact, it is a legal requirement of all physicians providing patient care. In the fast-paced Emergency Department, documentation is a particular challenge given the need for clinicians to achieve a balance between patient safety and department flow. The decision of what details to include in medical charts can be particularly difficult for learners, since developing knowledge and limited clinical experience can hinder your ability to decide which details are relevant to a case.

Start with Your Differential Diagnoses:

A helpful way to identify the appropriate content for a patient encounter is to have a working differential diagnosis in mind prior to assessing the patient. One approach often used in Emergency Medicine is to consider which possible diagnoses have high mortality and/or morbidity (“cannot miss”) and which diagnoses have the highest pretest probability in the patient population at hand (“most likely”). While not an exhaustive list of causes, this thought process can guide the information gathering process. It also helps learners recognize the pertinent positives and negatives of a case that should be documented, as a complete encounter note should rationalize the choice of investigations and management plan for this specific patient.

Before going to see your patient, you think through your differential diagnosis: cannot miss diagnoses include ectopic pregnancy, appendicitis, and bowel obstruction, while most likely diagnoses include urinary tract infection, pelvic inflammatory disease, and gastroenteritis. Among the things you want to ask about include a surgical history, sexual history, and travel history. You also think about special maneuvers on physical exam you want to perform, such as Rovsing’s and psoas signs, which assess for appendicitis.

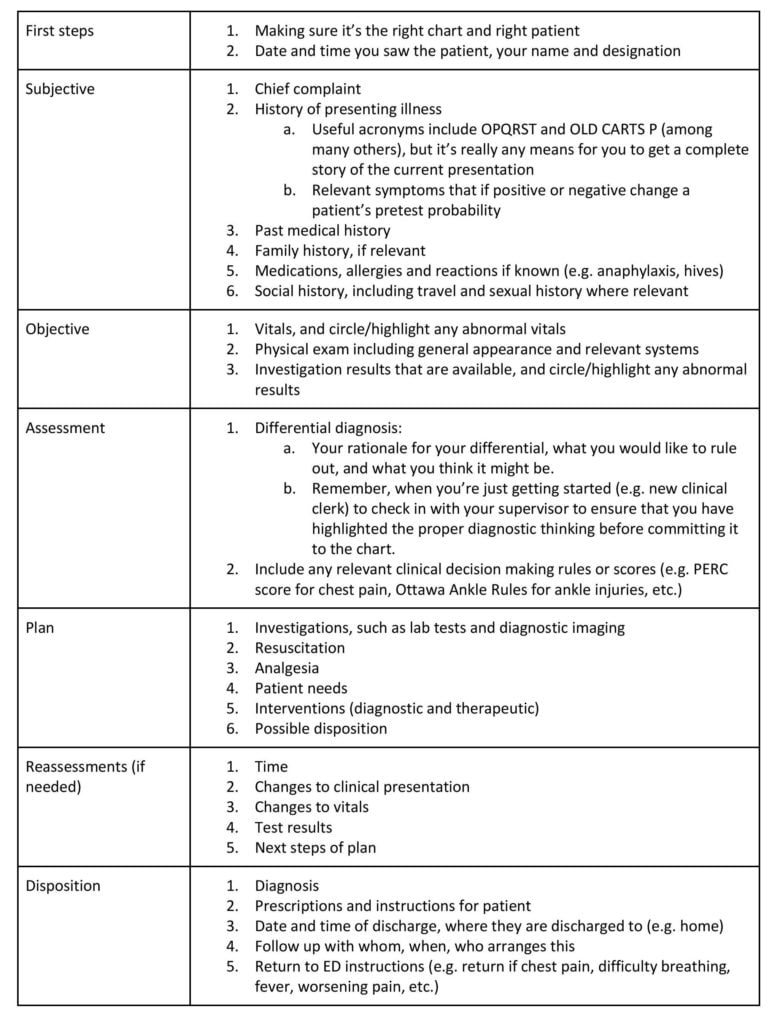

SOAP Note:

When it comes to documentation, the CMPA recommends using a SOAP note (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) as the most effective way to communicate information on a clinical encounter1. When first starting to learn this skill, a useful general template could contain the contents in the table below2, though some staff physicians may have specific preferences. For new clinical clerks especially, it’s good practice to adjust to the charting and preferences of the person with whom you’re working.

What to Include in the Chart:

Following a template seems simple enough, but that’s not the goal. The goal is actually to write a complete yet concise note that both supports patient care and safety while also helping to improve your clinical understanding as a learner. Again, the way to do this as a writer is to keep asking yourself whether or not a piece of information (1) changes the probability of the patient’s diagnosis and (2) potentially changes the management plan. If a piece of information doesn’t do one of these things, reflect carefully on how it adds value to patient care, and if it doesn’t it’s one less thing to write down and crowd your note with.

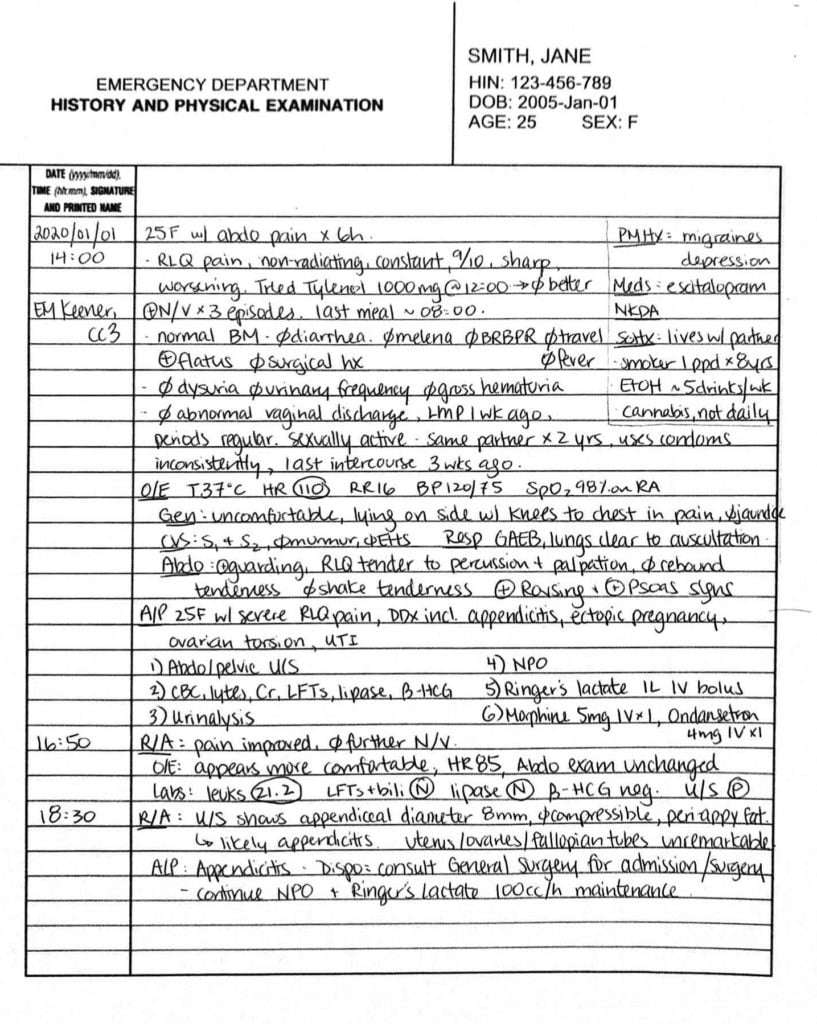

After seeing the patient, you chart a concise but thorough note. You review the patient with your preceptor and come up with a plan. After the results come back and you’ve reassessed the patient, it’s determined that the patient has appendicitis. You finish the rest of your patient chart.

Example Charts:

To better illustrate our approach here, let’s go through an example using the above template and discuss some suggestions for improvement:

- Use pertinent positives and negatives. Include information that influences the likelihood of the diagnoses on your differential. This has been done partially here but using a blanket review of systems (ROS) is not particularly useful where there is a clear chief complaint (1a). Being specific and identifying urinary symptoms, fever, travel history, etc. is a stronger and more targeted approach. Furthermore, for this particular case, the surgical and sexual history belongs up with other pertinent negatives, since ectopic pregnancy and bowel obstruction are important diagnoses to assess for in this scenario (1b).

- Address abnormal vitals. Get in the habit of circling/highlighting any abnormal vitals! This is so that you remember to address them in your management plan and on your reassessments, which is crucial for patient safety and for determining how sick a patient is.

- General appearance helps describe how unwell your patient looks. Being descriptive can be really helpful here – what makes you think that they are uncomfortable? Are they lying on their side with knees-to-chest in pain while crying? Or perhaps lying back in fear that any movement will cause pain? Writing this down helps your reader to better understand how sick this patient was.

- Always make a case for your assessment and what you want to rule out as part of your assessment. This is the rationale for your plan and a crucial step in your understanding of the case, it also gives your preceptor a chance to better teach around clinical reasoning.

- Document reassessments. Often forgotten, but how else does anyone know you’ve checked on the patient and reviewed the results of tests as they arrive? This also shows that you’ve addressed their previously abnormal vitals.

- Complete the disposition plan. Frequently new learners leave this to the senior resident or attending to do, especially when the diagnosis is somewhat unclear. However, your learning experience is enhanced by completing the patient chart. This gives your attending a chance to address any knowledge gaps (as they check your chart before they sign), which ultimately will make you a better doctor.

For comparison, here is the note rewritten with the suggested edits:

Different institutions provide varying amounts of space to document patient encounters (1 page vs 2 pages vs electronic charts that give you as much space as you need). Some charts also have specific sections for different details (e.g. past medical history, medications, lab results, orders) so in reality, you might not need to try to fit them all in one page. If space seems limited, check in with your staff physician and ask if you should leave space for them to write, and if so what they advise that you omit (e.g. some staff don’t like a thorough differential diagnosis documented). As a learner, your note will invariably be longer than your staff’s, and that is just a normal part of the learning process.

The Bottom Line:

Tedious as it may be, documentation is a fundamental skill that you will need throughout your career in medicine. After all, if you didn’t write it, it didn’t happen, and it’s your responsibility to capture what happened throughout the patient encounter.

For clinical clerks and even junior residents, using the process of documentation to organize your thoughts is helpful not only for your own understanding, but also for better communication with other providers (e.g. consultants). Think of it as a piece of writing that convinces the reader which diagnosis is most likely using the information you have collected, and use the process to also brainstorm which diagnoses you wouldn’t want to miss. While sometimes it seems easier to write down everything you can think of, I challenge you to continue the pursuit of writing succinct notes throughout your education, which will ultimately make this administrative task an easier one and help you to better enjoy your clinical job as a whole.

Good luck charting!

This post was edited by Megan Chu and Julia Heighton.

- 1.Canadian Medical Protective Association . How to Document. CMPA Good Practices Guide. https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/serve/docs/ela/goodpracticesguide/pages/communication/Documentation/how_to_document-e.html. Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 2.Canadian Medical Protective Association . What to Document. CMPA Good Practices Guide. https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/serve/docs/ela/goodpracticesguide/pages/communication/Documentation/what_to_document-e.html. Accessed April 30, 2020.

Reviewing with the Staff

This is an excellent summary of an approach to charting for those of you who are currently still using paper charts. However, many hospitals have gone towards electronic health records. It is important to understand that regardless of the types of charting you use - the core principles are the same.

When chatting electronically, it is even more important to check which patient chart you are writing within! It is easy to click into the wrong chart and write the wrong thing for sure.

Also, if you’re used to drawing illustrative pictures, it can be much harder to do so with a trackpad or a mouse. Make sure you learn all those complicated anatomical landmarks, and how to spell them! Spellcheck can fail you with complicated words!