A 3-year-old boy is brought to the ED by his anxious parents following a head injury he sustained while playing in the playground. He was running when he tripped and bumped his head against the metal steps. As you observe him calmly playing on his tablet in the waiting room, his parents are inquiring about the necessity of skull x-rays. You consider the role of such imaging in investigating pediatric head injuries – specifically how it compares to other modalities, like CT scans, which are often the first choice for most practitioners.

Background

In Canada, children under the age of 5 make up the largest proportion of ED visits for traumatic brain injuries (TBIs).[1] Not only do young children have higher rates of ED visits, but they are also more prone to intracranial injury due to their large head-to-body ratios, thinner skull bones, and decreased myelinated neural tissue.[2] You might be thinking to yourself that CT scans are extremely important given how prone they are to injury, however it is also important to bear in mind that children are more susceptible to the risks of radiation given that their brains are still developing and more sensitive to insults. Not to mention that CT scans are much more costly than simple radiographs. Thankfully, there are clinical decision-making rules that help physicians decide when CT scans are indicated in pediatric populations. However, what is the role of skull x-rays and when should they be used?

Skull X-Rays

Skull radiographs can be useful for identifying skull fractures but are less sensitive for intracranial bleeds and have more inter-observer variability compared to CT.[3-4] This could be in part due to the difficulty with differentiating cranial sutures from non-depressed fractures. Identifying skull fractures with imaging is important to physicians because they are known to be associated with higher incidence of intracranial bleeds and other complications.[5]

Gravel et al. conducted a prospective cohort study in Quebec to evaluate children under the age of 2 with mild head injury who didn’t meet criteria for head CT.[6] They found that only 5.6% of children had a skull fracture on x-ray and none of the children in the study developed complications or required neurosurgical intervention.[6]

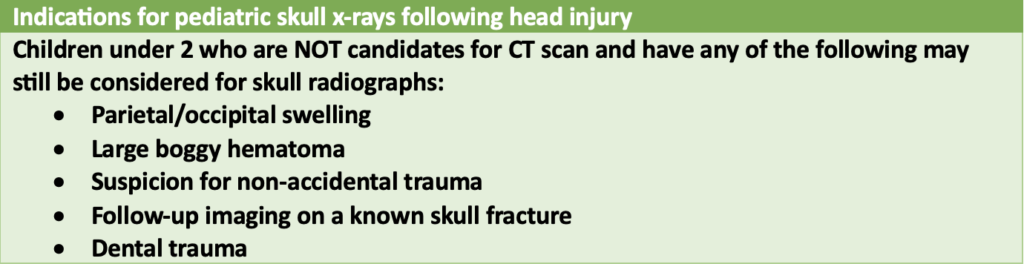

Based on their results, they developed a clinical decision rule that identifies about 90% of skull fractures in young children without clinically important TBI (ciTBI) based on two primary predictors: parietal/occipital swelling or hematoma and age less than 2 years. However, the study also found that none of the children with incidental skull fractures developed complications or needed intervention, suggesting that the clinical importance of isolated skull fractures is low.

There are some cases where it may be useful to identify a skull fracture even without reported trauma, such as in suspected cases of abuse, where skull fractures have a positive predictive value of 20.1%,[7] Additionally, before choosing between skull x-ray and CT, physicians must also consider individual patient characteristics, such as the risk of malignancy associated with ionizing radiation exposure and the potential risks of sedation and anesthesia required to perform a CT scan.[8]

CT Rules

There are two popular clinical decision rules for CT which are commonly used in the setting of pediatric head injuries.

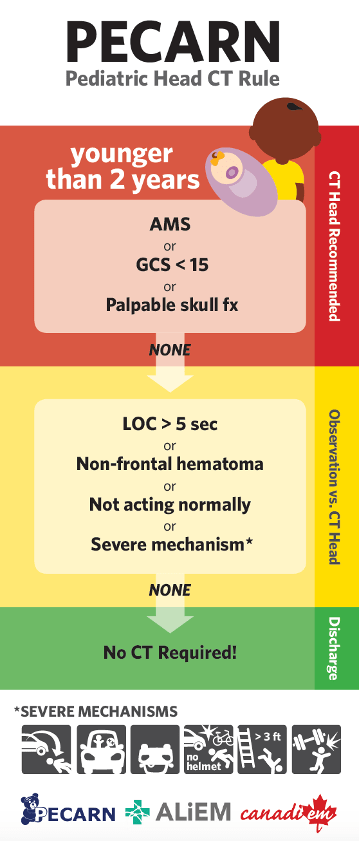

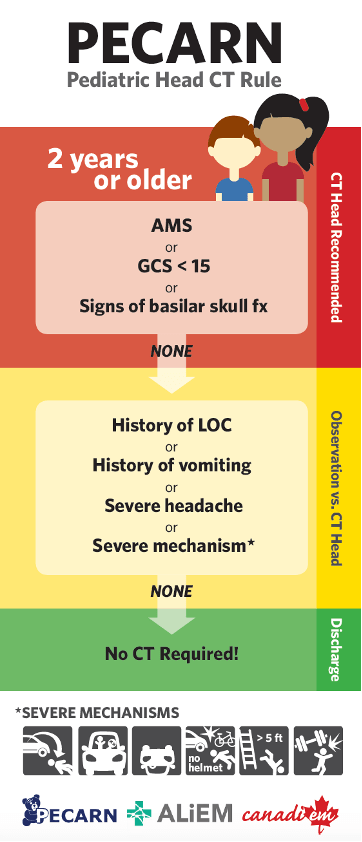

The first is the PECARN rule which was developed to rule out children with very low risk of clinically important TBI (ciTBI). It did a great job at this, considering it had a 100% sensitivity and 53.8% specificity for ciTBI in children younger than 2 years in the original study.[9] This has since been validated externally and found to be an accurate sensitivity for children younger than 2 years old, and 98.4% sensitive in children older than 2 years.[10] Essentially, if you think a child is low risk and are unsure whether to get a CT, this tool can help you safely decide if the risk of ciTBI is greater than the risk of radiation from the CT.

Figure 1 and 2: Infographics that outline the PECARN rule for children under 2 years of age or 2 years and older, respectively.[11]

The CATCH rule is another tool that can identify higher-risk patients with signs of head injury requiring a CT scan. It stratifies patients into a high-risk cohort, needing neurological intervention, or a medium-risk cohort with increased risk of having a brain injury seen on CT,[12] Although helpful in specific scenarios, physicians generally prefer PECARN due to its greater sensitivity and wider validation.[13-14]

Reading about PECARN and CATCH may increase your confidence in using CT as your imaging choice for detecting TBI, but keep in mind that the specificity of these rules remains low. This means that unnecessary CT scans may expose many children to radiation without intracranial lesions.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound imaging is another non-invasive tool that has been used to identify skull fractures. A systematic review identified POCUS as having a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 96% for identifying skull fractures,[15] making it a valid option for diagnosing skull fractures. However, ultrasound assessment of the head may be challenging or impossible in pediatric patients, as they may be excessively crying and irritable, making it difficult to maintain their head position during the scan [16]. Although promising, ultrasound imaging does not replace CT as the gold standard for diagnosing pediatric head injuries, is more dependent on user competence, and is currently better suited for risk stratification than for diagnosis.

Bottom Line

CT is considered the gold standard for diagnosing pediatric head injuries due to its greater sensitivity and reliability compared to x-rays, even for detecting skull fractures. However, the latest practice guidelines recommend that select groups of children under the age of 2 who do not meet the criteria for CT scanning should still be evaluated with x-ray, even though further research is needed to validate this approach.[17-18] Nonetheless, physicians should always consider individual patient characteristics, such as the likelihood of nonaccidental trauma, the risks of ionizing radiation for malignancy, and patient cooperation with necessary preparation for the imaging test, when making clinical decisions.

Back to the case: Since our little boy in the waiting room is 3 years old, if there is no indication to obtain a CT based on our clinical decision rules, and we have no clinical suspicion for nonaccidental trauma, we can safely discharge them home with close monitoring instructions, but no skull x-ray is required at this time.

Appendix:

This post was copyedited by Farzan Ansari and edited by Daniel Ting.

References:

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Injury in review, 2020 edition: Spotlight on traumatic brain injuries across the life course [Internet]. Canada.ca. Government of Canada; 2020 [cited 2023Feb16]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/injury-prevention/canadian-hospitals-injury-reporting-prevention-program/injury-reports/2020-spotlight-traumatic-brain-injuries-life-course.html

- Sookplung P, Vavilala MS. What is new in pediatric traumatic brain injury? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009 Oct;22(5):572-8. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3283303884.

- O’Brien WT Sr, Caré MM, Leach JL. Pediatric Emergencies: Imaging of Pediatric Head Trauma. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2018 Oct;39(5):495-514. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2018.01.007.

- Kim YI, Cheong JW, Yoon SH. Clinical comparison of the predictive value of the simple skull x-ray and 3 dimensional computed tomography for skull fractures of children. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012 Dec;52(6):528-33. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.52.6.528.

- Chan KH, Yue CP, Mann KS. The risk of intracranial complications in pediatric head injury. Results of multivariate analysis. Childs Nerv Syst. 1990 Jan;6(1):27-9. doi: 10.1007/BF00262262.

- Gravel J, Gouin S, Chalut D, Crevier L, Décarie JC, Elazhary N, Mâsse B. Derivation and validation of a clinical decision rule to identify young children with skull fracture following isolated head trauma. CMAJ. 2015 Nov 3;187(16):1202-1208. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150540.

- Donaldson K, Li X, Sartorelli KH, Weimersheimer P, Durham SR. Management of Isolated Skull Fractures in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(4):301-308. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001814.

- McGrath A, Taylor RS. Pediatric Skull Fractures. [Updated 2023 Jan 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482218/

- Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, Hoyle JD Jr, Atabaki SM, Holubkov R, Nadel FM, Monroe D, Stanley RM, Borgialli DA, Badawy MK, Schunk JE, Quayle KS, Mahajan P, Lichenstein R, Lillis KA, Tunik MG, Jacobs ES, Callahan JM, Gorelick MH, Glass TF, Lee LK, Bachman MC, Cooper A, Powell EC, Gerardi MJ, Melville KA, Muizelaar JP, Wisner DH, Zuspan SJ, Dean JM, Wootton-Gorges SL; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009 Oct 3;374(9696):1160-70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61558-0. Epub 2009 Sep 14. Erratum in: Lancet. 2014 Jan 25;383(9914):308.

- Schonfeld D, Bressan S, Da Dalt L, Henien MN, Winnett JA, Nigrovic LE. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network head injury clinical prediction rules are reliable in practice. Arch Dis Child. 2014 May;99(5):427-31. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305004.

- CanadiEM. PECARN Pediatric Head CT Rule [Image on internet]. 2017 [cited 2023Apr02]. Available from: https://canadiem.org/the-pecarn-pediatric-head-ct-rule-project/

- Osmond MH, Klassen TP, Wells GA, Correll R, Jarvis A, Joubert G, Bailey B, Chauvin-Kimoff L, Pusic M, McConnell D, Nijssen-Jordan C, Silver N, Taylor B, Stiell IG; Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) Head Injury Study Group. CATCH: a clinical decision rule for the use of computed tomography in children with minor head injury. CMAJ. 2010 Mar 9;182(4):341-8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091421. Epub 2010 Feb 8. PMID: 20142371; PMCID: PMC2831681.

- Lyttle MD, Cheek JA, Blackburn C, Oakley E, Ward B, Fry A, Jachno K, Babl FE. Applicability of the CATCH, CHALICE and PECARN paediatric head injury clinical decision rules: pilot data from a single Australian centre. Emerg Med J. 2013 Oct;30(10):790-4. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201887.

- Easter JS, Bakes K, Dhaliwal J, Miller M, Caruso E, Haukoos JS. Comparison of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE rules for children with minor head injury: a prospective cohort study. Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Aug;64(2):145-52, 152.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.01.030.

- Alexandridis G, Verschuuren EW, Rosendaal AV, Kanhai DA. Evidence Base for Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) for Diagnosis of Skull Fractures in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2022;39:30-36. doi:10.1136/emermed-2020-209887.

- Abdallah R, Hemeda TW, Elhady AM. Ultrasound in Detection of Skull Fractures in Children Younger Than Two Years Old with Closed Head Injuries. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2021;114(1):332. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcab106.003.

- Farrell CA, Canadian Paediatric Society, Acute Care Committee. Management of the paediatric patient with acute head trauma. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2013;18(5):253–8. doi: 10.1093/pch/18.5.253

- Nour A, Goldman RD. Skull X-ray scans after minor head injury in children younger than 2 years of age. Canadian Family Physician. 2022Mar;68(3):191–3.

Reviewing with the Staff

Pediatric head injuries are common presentations in Canadian emergency departments. These patients have a small but important risk of significant intracranial injury. Diagnostic assessment can be standardized and improved with clinical decision rules. These diagnostic algorithmic tools are based on risk factor assessment and encourage the selective use of CT to help minimize unnecessary radiation. PECARN and CATCH are two of the commonly used decision rules for pediatric head injuries. It is also important to understand the role of plain radiography such as skull x-rays in the evaluation and assessment of pediatric head trauma. In this vulnerable population, the risk of missed traumatic brain injury must be weighed against the risk of unnecessary diagnostic imaging and radiation exposure. This article provides a useful resource for busy emergency physicians outlining the current guidelines.