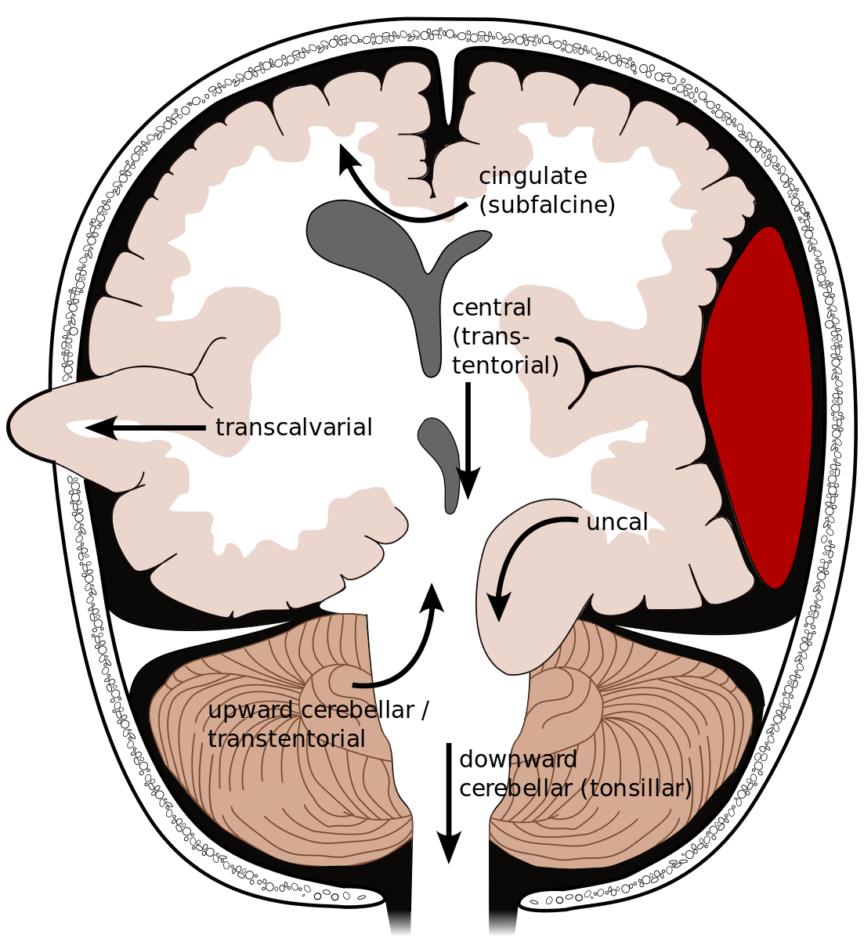

Brain herniation is a catastrophic sequela of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) or local mass effect from intracranial lesions. Different types of brain herniation can occur depending on the location of mass effect and how rapidly this mass effect develops.1 Any mass lesion, including hemorrhage, tumor, vasogenic or cytotoxic edema, trauma or infection can cause herniation. However spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) are common causes of herniation in the acute setting this is frequently related to trauma ± hemorrhage. There are two classic brain herniation syndromes that should be considered for patients presenting acutely. These are the supratentorial uncal herniation syndrome and the infratentorial tonsillar herniation.

Uncal herniation is the herniation of the uncus, which is a part of the anteromedial portion of the temporal lobe. The uncus herniates medially into the tentorial notch, causing compression on the 3rd nerve then brainstem as it progresses. Uncal herniation results in a classic uncal herniation syndrome involving ipsilateral cranial nerve III palsy (fixed, dilated, so-called ‘blown’ pupil), coma, and contralateral hemiparesis. The earliest reliable sign is the ipsilateral blown pupil. The significance of decreased level of consciousness should not be ignored in these patients.1

- Ipsilateral blown pupil

- Consciousness (decreased)

- Hemiparesis (contralateral)

Tonsillar herniation is a posterior fossa herniation characterized by herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. This results in compression of the brainstem, which contains many important homeostatic centers including centers that regulate breathing and consciousness. Tonsillar herniation causes the Cushing reflex, consisting of irregular breathing, bradycardia, and hypertension. Pay special attention to the patient with high intracranial pressure and bradycardia.

- Irregular breathing

- Cardiac (bradycardia)

- Hypertension

A patient presenting with either of these constellations of symptoms should have urgent management of their intracranial pressure and immediate neurosurgical consultation. Non-operative methods for ICP management include elevating the head of the bed to 30 degrees, osmotic agents such as hypertonic saline or mannitol, and sedation with opioids or paralytics.2 Hyperventilation to a PCO2 of 30-35 mmHg may be used as a temporizing measure.3 Neurosurgery may place an external ventricular drain (EVD) in order to divert CSF and reduce intracranial pressure. When stable, an emergent CT of the head should be urgently arranged to determine the etiology of the herniation.

Definitive treatment is with emergent decompression; at early stages, deficits may be reversible, but overall efficacy of decompression for herniation is dependent on the etiology of the herniation. For lesions such as acute epidural hematomas the outcomes are excellent whereas in diffuse traumatic brain injury benefits are less certain.4 Uncal herniation is treated with decompressive hemicraniectomy or removal of the mass lesion, and failure to treat this condition promptly can result in persistent third nerve palsy, hemiparesis, coma, or death. Tonsillar herniation is treated with posterior decompression, and failure to treat promptly results in respiratory arrest and death.

References

Reviewing with the Staff

ICH for ICH is a great way of remembering the clinical signs of uncal herniation: ICH [Ipsilateral blown pupil, Consciousness and hemiparesis (contralateral)] and the classic Cushing’s triad, ICH (Irregular breathing, Cardiac-Bradycardia and Pressure-Hypertension). Patients who present with a depressed level of consciousness, new onset or worsening headaches, nausea, vomiting, new or worsening focal neurological deficits or patients who have signs of raised intracranial pressure on imaging studies such as sulcal effacement, effacement of cisterns, midline shift should be managed emergently. Remember that herniation is a potentially reversible process depending upon the timing of presentation and the underlying etiology. Preventing secondary neurological injury is a very important goal in these patients. Although emergent imaging is needed for establishing diagnosis and identifying strategies for definitive management, before transporting a patient with clinical signs of raised intracranial pressure to radiology, secure the airway paying special attention to preventing any hypoxia, hypoventilation, hypotension or hypertension. Simple measures instituted quickly at the bedside could be potentially life saving such as maintaining the head in the midline, head of bed at 30 degrees, hypertonics, neuroprotective airway and hemodynamic management, hyperventilation, sedation, analgesia can all be addressed quickly at the beside even before imaging is obtained. Surgical decompression including the need for an Extraventricular device (EVD) for CSF diversion, decompressive hemicraniectomy etc. must be addressed as rapidly as possible. Time is Brain!