This article is the second in a two-part series discussing the reciprocal relationship between climate change and emergency medicine (EM). Part one addressed how the effects of climate change disproportionately impact vulnerable populations. It explored how heat waves, atmospheric pollution, and natural disasters are directly related to climate change and how they affect people’s health. The resulting health problems amplify pressures on already overloaded and strained emergency departments (EDs). This article will address the impact of healthcare practices on the environment and opportunities for emergency physicians to reduce them from an individual, hospital, and systems-level approach.

Relevance

Healthcare contributes to 4.6% of global greenhouse gas emissions and this is expected to increase in the coming years.1 According to the Lancet, climate change was identified as the “biggest global health threat of the 21st century”.2 In response to the growing threat of climate change, the 26th Conference of Parties (COP) was held in 2021 to address the problem. At COP26, Canada signed a commitment to building “climate-smart” health systems which prioritize low-carbon, sustainable, and climate-resistant health strategies.3 This drive was further intensified at the recent COP27 with further calls to action for green health systems.4

Impact of COVID-19 on the environment

Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic has slowed progress toward more climate-resistant health systems. As patient loads and stress on healthcare providers increased, managing waste was understandably not the highest priority. As of November 2021, United Nations shipments of COVID-19-related PPE to distribute to developing countries were around 87,000 tonnes (filling 261,747 jumbo jet airplanes).5 It is estimated that all single-use PPE will (or has) become waste. The United Nations Development Program estimated that hazardous healthcare waste has increased tenfold from pre-pandemic levels of 0.2-0.5kg/bed/day to an estimated 3.4kg/bed/day.5 Unfortunately, many health systems unnecessarily categorized 100% of COVID-19 waste as hazardous (and thus requiring more energy-consuming, carbon-emitting disposal processes) whereas typically 10-15% of the waste produced from normal healthcare delivery patterns is considered hazardous.5

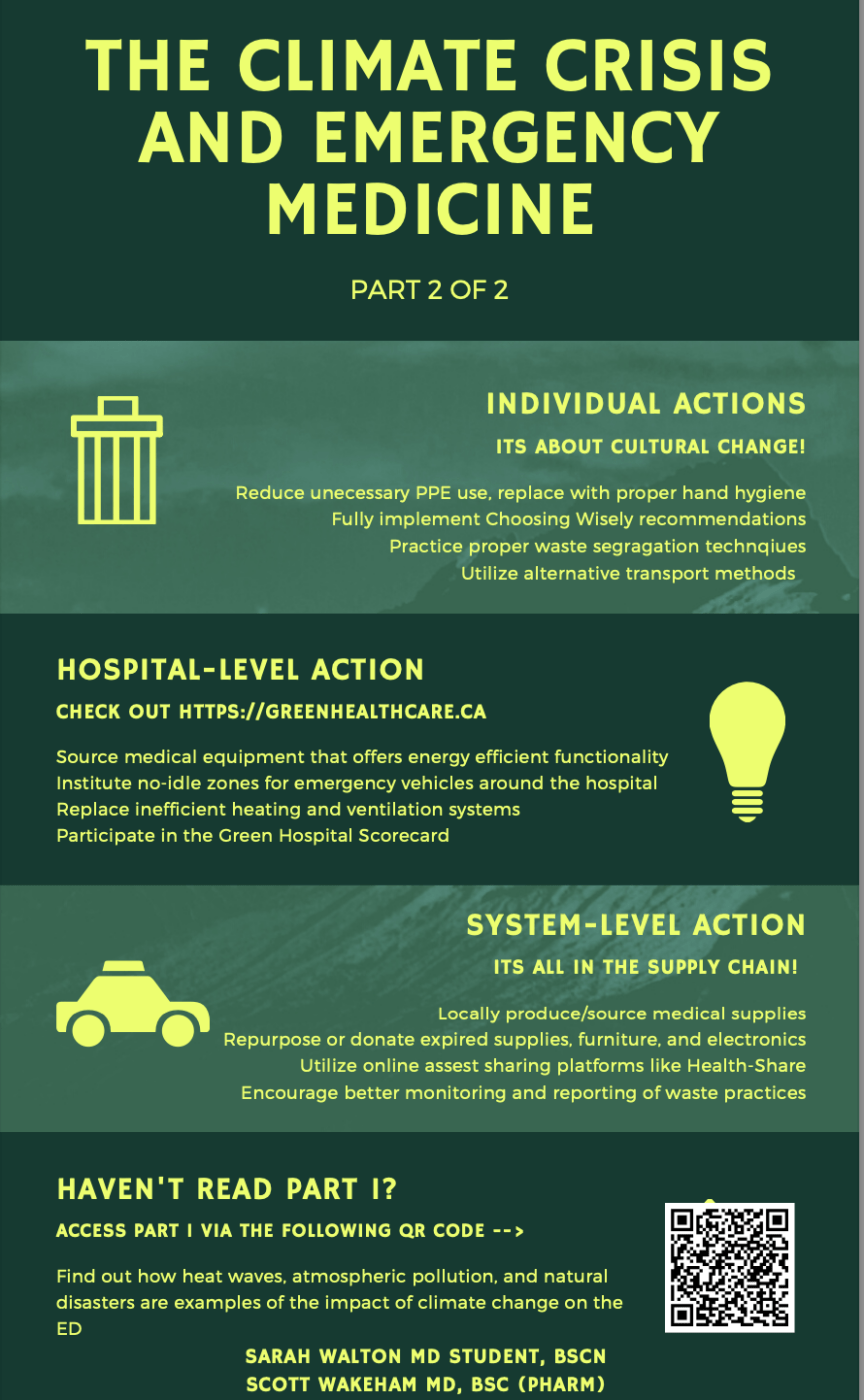

Individual actions

Individual actions, although small in environmental impact, can lead to important cultural change within EDs and the greater health system. For example, reducing unnecessary plastic glove and cup use has significant benefits.5,6 Taking the stairs instead of the elevator or choosing to give a patient an electronic resource instead of a traditional pamphlet helps to promote a culture of sustainability. A continued understanding of Choosing Wisely recommendations that reduce unnecessary testing and medication use also contributes to a sustainable health system. In the wake of the pandemic where PPE was sometimes used without distinction, individuals should still remain aware of reducing unnecessary PPE use while maximizing effective hand hygiene.5

Recycling alone does not add a significant environmental benefit. However, by collecting and reprocessing materials used in the ED like food and beverage containers, paper, plastics, and glass, waste can be diverted from landfills and incinerators. Thus, on a small scale, it contributes to improved waste segregation practices.7 Within the National Health Service, appropriately segregating waste to avoid unnecessary landfill and incineration had a projected savings of 40 tons of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e) and a savings of $48,000 CAD per year.6 CO2 emissions make up most global greenhouse gas emissions and the average Canadian produces approximately 19 tons of CO2e per year. One ton of CO2 would fill a 10-metre diameter sphere. Approximately one ton of CO2 is produced by an average car driving 4000 kilometres.8

Emergency staff can utilize alternative transport methods to work such as public transport, rideshare programs, bikes, or scooters which drastically reduce one’s carbon footprint.6 Emergency staff are uniquely situated to be early adopters and role models when it comes to climate-smart healthcare practices, and should consider starting or joining a local “green team” that promotes sustainability at their individual workplaces.7 Perhaps the most significant individual-level action that emergency physicians can take is to push forward and/or lead some of the example hospital- and system-level actions below.

Hospital-level actions

Energy conservation, repurposing supplies, and taking part in the Green Hospital Scorecard are all strategies to become more climate-smart on a larger scale. Energy conservation includes upgrading heating, air conditioning, and ventilation systems when old systems need replacing. Sourcing medical equipment that offers energy-efficient functionality is encouraged.7 Low energy lighting (i.e., LED) had a predicted reduction of 520 tonnes of CO2e and cost savings of $260,000 CAD per year in the UK.6 Turning monitor brightness down and using automatic nighttime shutdown for appropriate computers requires no additional upfront cost and saves energy.9 Adopting reusable sharps bins that do not need to be incinerated along with their contents limits single-use plastic.9 By employing some of these simple energy-saving operational and equipment improvements, some American hospitals have saved the equivalent of $1.3 billion CAD during a five-year period.9 In Canada, the Canadian Healthcare Engineering Society’s (CHES) goal is to improve energy efficiency in healthcare facilities. Their projects have already saved 1.1 megawatts of electricity and 4.6 gigawatt hours of energy to date.10 One gigawatt equals one billion watts and is enough energy to power about 750,000 homes.11 CHES’ projects in Ontario alone will save $15 million CAD annually in utility costs when they are completed.10

Hospitals can institute no-idling zones for all emergency vehicles.7 When emergency vehicles need to be replaced, cost-effective alternative fuel vehicles should be considered.7

Through the Canadian Coalition for Green Health Care, hospitals can take part in the Green Hospital Scorecard. Hospitals can benchmark and compare themselves against 10 sustainability variables. They can track their progress toward sustainability over time and compare with other participating sites. Ontario and British Colombia overwhelmingly lead the country in all areas of sustainability to date.10

Systems-level actions

At a healthcare systems level, the greatest environmental benefit will come from supply chain improvements. Globally, only 17% of all healthcare-related greenhouse gas emissions come directly from healthcare facilities.6 Shockingly, 71% of all healthcare-related emissions come from the procurement of goods or services.6 The healthcare supply chain contributes to pollution largely through the transportation of huge amounts of waste, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and high demands on food production and disposal.7

By advocating for local production of medical supplies, there can be significant decreases in supply chain disruptions, shipping costs, and carbon emissions.5 In the UK, there could be a 12% decrease in the carbon footprint required for PPE production (12,491 tonnes of CO2e) over a six-month period if PPE was manufactured locally.12 Local manufacturing could also lead to increased ownership over how efficiently healthcare materials are packaged.5

Clinical supplies, equipment, furniture, and electronics that can no longer be used or have expired can be reused or donated to other departments or facilities in need.7 In Canada, online asset-sharing platforms like Health-Share facilitate this process. By doing so, they promote a circular procurement model and lessen the impact on the supply chain.12 During the pandemic, Health-Share enabled hospitals to procure PPE supplies by using the platform to interact with local suppliers and secure the required equipment.12

Canada has no regular monitoring or reporting of healthcare waste practices. Additionally, there is a gap in EM-specific research quantifying the impact that EDs have on the environment. Regular monitoring and reporting of waste practices are vital in creating environments that prioritize sustainability and accountability.5 Until concrete data on healthcare-related waste production and resource utilization is available, few significant changes can be rationally considered or implemented.

Conclusion

In taking measures to become informed and active in planetary health, emergency staff can better care for patients of the present and future. At a time when the demands on EM seem to be at their peak, it is essential to maintain a future-oriented view of healthcare delivery that is resilient to the ever-growing incidence of natural disasters outlined clearly in part one of this series. EM has been pivotal in pandemics and crises of the past. The climate emergency is a significant healthcare crisis that we are already facing. Without significant adaptation to and mitigation of climate change, our health systems will not withstand the resulting health effects. Emergency staff can lead the way to system-wide change that ensures quality healthcare delivery for generations to come.

This post was copyedited by Tim Zhang (@_timothyzhang) and edited by Daniel Ting.

References

- 1.Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, et al. The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. The Lancet. Published online November 2019:1836-1878. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32596-6

- 2.Costello A, Abbas M, Allen A, et al. Managing the health effects of climate change. The Lancet. Published online May 2009:1693-1733. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60935-1

- 3.Smith P, Beaumont L, Bernacchi CJ, et al. Essential outcomes for COP26. Global Change Biology. Published online October 25, 2021:1-3. doi:10.1111/gcb.15926

- 4.Health care climate action gains momentum from COP26 to COP27 . Health Care Climate Action. Published March 8, 2023. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://healthcareclimateaction.org/COP27_mediaadvisory

- 5.Global analysis of health care waste in the context of COVID-19 . World Health Organization. Published March 8, 2023. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039612

- 6.Spruell T, Webb H, Steley Z, Chan J, Robertson A. Environmentally sustainable emergency medicine. Emerg Med J. Published online January 22, 2021:315-318. doi:10.1136/emermed-2020-210421

- 7.Linstadt H, Collins A, Slutzman JE, et al. The Climate-Smart Emergency Department: A Primer. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Published online August 2020:155-167. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.11.003

- 8.Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions . Government of Canada. Published March 8, 2023. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions.html

- 9.Sorensen CJ, Salas RN, Rublee C, et al. Clinical Implications of Climate Change on US Emergency Medicine: Challenges and Opportunities. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Published online August 2020:168-178. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.03.010

- 10.The Green Health Care Report 2020-2021. Greenhealthcare.ca. Published March 8, 2023. Accessed November 27, 2022. https://greenhealthcare.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/The-Green-Health-Care-Report-2020-21.pdf

- 11.How Much Power is 1 Gigawatt? U.S. Department of Energy. Published March 8, 2023. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.energy.gov/eere/articles/how-much-power-1-gigawatt

- 12.Zarocostas J. WHO concerned over COVID-19 health-care waste. The Lancet. Published online February 2022:507. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00225-2

Reviewing with the Staff

While the effects of climate change have been slowly slipping their way into our daily practice as emergency physicians for years, the increasing frequency of extreme weather events in Canada is something we can no longer ignore.

Climate change is, and will be, the great health emergency of our time, and it is our responsibility as healthcare providers for the most vulnerable to answer the call of duty to mitigate the effects of climate change to protect our patients. By publicly committing to pursuing a greener ED, one can start with individual steps that will hopefully ignite the desire to drive change at the hospital or systems level. This is one of the few areas of primary prevention that we as emergency physicians can directly practice for the good of our current and future patients.