Donna is a 48-year-old female brought by EMS to your community ED after her roommates noticed her behaving erratically at home. They report she has been vomiting and become increasingly confused over the past 24 hours, now complaining of right upper quadrant discomfort. She was recently discharged from the hospital a week ago following an uncomplicated ankle ORIF. Donna’s roommates tell you she is otherwise healthy, but does consume two to three glasses of wine per day recreationally. The only medication she is on is acetaminophen for post-op pain control, since she lost her prescription for oral hydromorphone at discharge.

Donna herself tells you that she was in considerable ankle pain following her operation. When asked how much medication she used, she reports “taking them until the pain goes away”.

At bedside Donna is GCS 14 and oriented to person and place. She was given a 1 L bolus of IV fluids already by EMS for hypotension during transport, but her most recent measurement still reads 90/65. She is afebrile and tachycardic at 120 bpm, with a RR of 20 and oxygen saturations of 97% on room air. Her chest is clear, and her abdominal exam is significant only for dull RUQ tenderness. She appears jaundiced, but there is no asterixis. Her pupils are 4 mm bilaterally and reactive to light. Her neurological exam appears grossly normal, but is confounded by poor effort.

As you think about Donna’s case you are sure to keep your differential and investigations broad, but start to dust off that place in your brain that stores all that knowledge about liver emergencies.

Background

Being familiar with acute abdominal pathologies comes with the trade of practicing emergency medicine. It’s a wonder then why we tend to gloss over the largest organ in the abdomen – the liver. Perhaps it is because liver emergencies are relatively rare when compared to other abdominal presentations like appendicitis or cholecystitis. However, given its high morbidity and mortality, it is important to recognize liver failure early on and to be comfortable with the management considerations that surround it.

Liver failure in the emergent context can be broadly classified into two categories. The first is true acute liver failure, which refers to impaired synthetic function (INR ≥ 1.5) and altered mental status with an illness duration of <26 weeks (depending on etiology, this timeline can be much shorter).1 Importantly, acute liver failure manifests in often otherwise healthy patients without prior cirrhosis or liver disease. When fulminant liver failure manifests in the presence of pre-existing hepatic co-morbidities, this is referred to as acute-on-chronic liver failure.2

Clinical Features and Causes

These patients most commonly present with the following clinical features:1,3

- Right upper quadrant pain or discomfort

- Malaise, lethargy, or general unwellness

- Signs of hepatic encephalopathy and increased intracranial pressure (e.g., altered level of consciousness, neurological deficits, asterixis)

- Nausea/vomiting

- Abdominal distension

- Hypotension, sepsis, and seizures in more severe cases

Investigations commonly show the following findings (variable, and many other abnormalities may exist depending on etiology):1,3,4

- Prolonged prothrombin time, with INR ≥ 1.5

- Thrombocytopenia

- Marked elevation in aminotransferases and bilirubin ± elevation in lipase and amylase

- Hypoglycemia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia ± hyperammonemia

- Anion gap metabolic acidosis (typically lactic acidosis)

What causes fulminant liver failure?

While hepatitis A and E cause the majority of acute liver failure cases worldwide, the etiology in developed countries is most commonly acetaminophen overdose or drug-induced liver injury.1 Table 1 below summarizes the common causes of acute and acute-on-chronic liver failure.

| Acute liver failure (patients with previously healthy livers)3 | Acute-on-chronic liver failure (patients with pre-existing cirrhosis/liver disease)2 |

| Infectious • Hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E • Adenovirus • Herpes simplex virus • Cytomegalovirus • Epstein-Barr virus Hepatotoxins • Acetaminophen • Drug-induced liver injury • Amatoxin-containing mushrooms Metabolic • Wilson disease, HELLP/AFLP • Various congenital genetic disorders Hypoperfusion/ischemia • Trauma • Malignant infiltration • Veno-occlusive disease | Infectious • Sepsis • Pneumonia • Urinary Tract Infections • Clostridium difficile infections • Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis Hepatotoxins • Acetaminophen • Alcohol use • Drug-induced liver injury Hypoperfusion/ischemia • Upper GI bleed • Trauma • Malignant infiltration • Major surgery |

Clinical Approach

Given the non-specific nature of presenting symptoms, it is important to consider liver failure early in the differential for patients with altered mental status, abdominal discomfort, and/or systemic unwellness – regardless of the suspected health of their liver at baseline.1,3

A detailed history should focus on homing in on the etiology of liver failure as well as clarifying the time course, which has both diagnostic and prognostic implications.5 The physical exam should center around confirming underlying liver pathology (jaundice, hepatomegaly, or other stigmata of liver disease) and recognizing encephalopathy or elevated intracranial pressure via a focused neurologic exam.

Given how unwell these patients can be, it is important to prioritize ABCs, establish IV access, and clarify fluid status early on. Liver failure patients typically present with depleted intravascular volume, which should be managed as a priority.3,4 Neurological status varies greatly depending on the degree of encephalopathy – if deemed to be severe, then definitive airway management should also be considered.

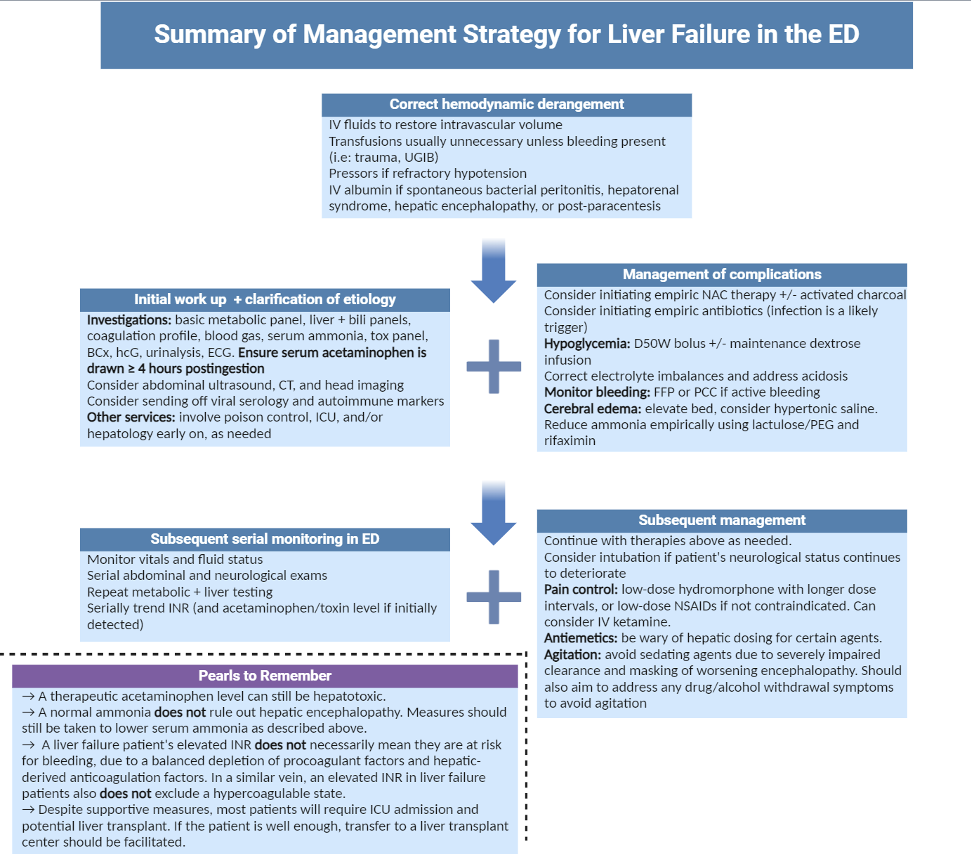

Management from this point will depend greatly on the patient’s clinical status/presenting features, medical history, and what the underlying cause of their acute liver failure was in the first place. In general, management principles include:

- Initiating treatment for hepatotoxic compounds

- Addressing metabolic disturbances (with particular attention to glucose)

- Attempting to reverse progression of hepatic encephalopathy ± cerebral edema

- Treating other complications of liver failure (bleeding, infection, emesis, pain, etc.)

- Trending lab values, vitals, and clinical status

- Involving necessary services and considering disposition to liver transplant center

Circling Back to The Case

Your initial set of investigations for Donna confirm a marked hepatic enzyme elevation, along with impaired synthetic function via a significantly elevated INR. Donna is also found to be hypoglycemic, and acidotic, with various other metabolic disturbances. Abdominal imaging is unremarkable. Her acetaminophen level is supratherapeutic. Toxicology work-up is otherwise unremarkable.

These findings in combination with the timeline and nature of her symptoms suggest she is likely in Stage II or III of acetaminophen poisoning with acute liver failure and signs of encephalopathy.6 Although she did not have any pre-existing liver disease to our knowledge, a combination of her supratherapeutic dosing and susceptibility to hepatotoxicity (possibly secondary to her regular alcohol use) explain her symptom onset and presentation.

Using the management principles outlined above, we should consider doing the following:

- Correct hemodynamic instability: Given Donna remains hypotensive in the absence of any bleeding (and assuming her hemoglobin is within normal limits), it is reasonable to continue resuscitation with fluids. If her hemodynamics do not improve, then pressors would be the next option.

- Initiate treatment for acetaminophen poisoning: A revised Rumack-Matthew nomogram can be used to contextualize her acetaminophen toxicity and guide treatment. Given the longer timeline since the start of her supratherapeutic ingestions, Donna will require empiric N-acetylcysteine. Involve poison control and continue trending serum acetaminophen.

- Correcting metabolic disturbances: Donna’s metabolic disturbances (particularly serum glucose) should be promptly addressed via IV dextrose and other corrective means. Particular attention to addressing even minor hypokalemia may help reduce ammonia accumulation.

- Address hepatic encephalopathy/cerebral edema: Given the acute onset and mostly reassuring neurological exam, Donna’s hepatic encephalopathy may be mild, but should be closely monitored. Initiating supportive measures for this should still be considered.

- Address other complications: Treatment for Donna’s nausea/vomiting and pain should be initiated (with caution to avoid sedating agents and other medications that are contraindicated in liver patients). If Donna’s mental status continues to decline, then her airway should be secured with endotracheal intubation. Continue to trend labs, with particular attention to INR, glucose, liver enzymes, and acetaminophen levels.

- Involving other services and disposition planning: Patients like Donna with liver failure may continue to deteriorate. If she is stable enough, transfer to a tertiary center with a liver transplant service should be considered. At the very least, ICU and local gastroenterology services may be worth involving.

This post was copyedited by Mackenzie MacAuley and was edited by Daniel Ting.

References

- 1.Montrief T, Koyfman A, Long B. Acute liver failure: A review for emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(2):329-337. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.032

- 2.Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R, Ginès P, EASL-CLIF Consortium CANONIC Study. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: A new syndrome that will re-classify cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 Suppl):S131-43. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.045

- 3.Bernal W, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2525-2534. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1208937

- 4.Helman A, Himmel W, Steinhart B. Ep 148 Liver Emergencies: Acute Liver Failure, Hepatic Encephalopathy, Hepatorenal Syndrome, Liver Test Interpretation & Drugs to Avoid. Emergency Medicine Cases. 2020. Accessed March 24, 2024. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/liver-emergencies-acute-liver-failure-hepatic-encephalopathy-hepatorenal-syndrome-liver-test-interpretation/#

- 5.Marudanayagam R, Shanmugam V, Gunson B, et al. Aetiology and outcome of acute liver failure. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11(5):429-434. doi:10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00086.x

- 6.Saccomano S. Acute acetaminophen toxicity in adults. Nurse Pract. 2019;44(11):42-47. doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000586020.15798.c6

Reviewing with the staff

Acute liver failure is less common than typical bread-and-butter sources of abdominal pathology, but it is an important one to recognize early on in a patient’s course. This can be difficult, as many patients present early with general malaise, non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms, or altered mental status, which carry broad differentials. Because of its high morbidity and mortality as well as multi-system organ involvement, it is key to understand how to cast a wide net of investigations, initiate treatment, involve other services as early as possible, anticipate potential complications, and avoid common pitfalls in management. In our Canadian context, remember to think of acetaminophen and other drug toxicities as the most likely culprit.